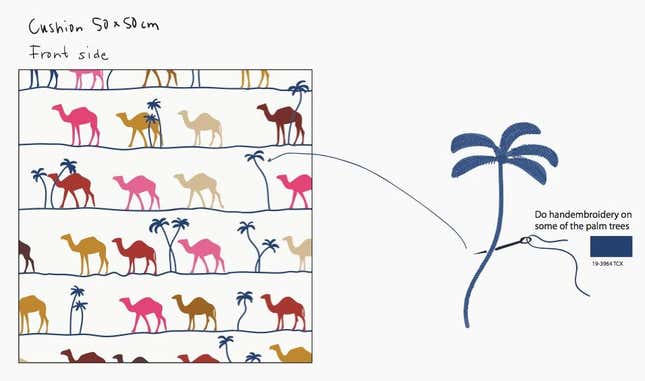

In the backroom of an airy workshop in Amman, Jordan, about a dozen Syrian and Jordanian women are sitting next to each other embroidering palm trees between rows of camels. Nearby, another group form an assembly line for pink tassels, with two women counting and re-counting the fine threads that go into each bundle. Next to them are seamstresses who attach the swingy fringes to a cactus-printed fabric by hand. On another floor, new trainees are practicing their machine sewing skills on large patterned floor cushions.

With great focus and palpable camaraderie, these 100 Syrian and Jordanian artisans are racing to deliver their first batch of handcrafted products ordered by IKEA.

In February this year, IKEA put into motion a long-term plan to employ Syrian refugee women in Jordan, specifically from the 80% of displaced migrants who live outside of the country’s five refugee camps. The number of women employed is small, but those who work here say getting a big order from a global corporation like IKEA life-changing: A Syrian mother is able to earn enough money for her family while her husband is still struggling to get a work permit. One teen in the sewing department says the training has inspired her to open her own boutique one day.

“I raise my children on my own and I’ve been divorced for five years,” says Tahani Al Khatib who works on embroidering IKEA products at home. “To work in Amman as a mother with children is very, very difficult and this is the only job that guarantees my income.”

A business collaboration, not a charity

“This is not a charity,” explains Vaishali Misra, head of IKEA’s five-year old social entrepreneur initiative. Instead of hiring thousands of refugees for seasonal work, IKEA says they’re interested in providing steady, year-round jobs. “It’s a long-term partnership that we have. This fits very well in in our strategy of making life better for many more,” says Misra during an Oct. 3 press tour of the workshops in Jordan.

Each artisan is paid a salary equal or above the legal monthly minimum wage of 220 dinars ($310) set by Jordanian government. Workers who work from home and not in the IKEA factory are compensated based on the number of pieces they produce. They also receive social security benefits and insurance.

Many artisans start-off as at-home workers. They work on IKEA orders in between cooking meals for their families or caring for their children. Many eventually go in to Jordan River Foundation’s workshop to be with other women a few times a week.

“We sit here to exchange recipes while we work,” smiles a woman used to be an elementary school teacher in Syria . “We also have a healthy competition on who can sew the fastest!,” adds the woman next to her, working away on her row of embroidered camels.

Misra says it’s a win-win for IKEA and the artisans. “We’re getting unique hand crafted products with a strong story behind it,” she says. IKEA’s in-house designers also get the rare opportunity to collaborate with artisan groups around the world and come back more inspired. The company plans to hire a total of 400 Syrian artisans by 2020.

Professionalizing a craft

IKEA has committed to integrating the Jordanian workshops—and all the social enterprises they partner with—in their famous, hyper-optimized supply chain.

To start, they’re training product standards concepts to the first group of Syrian and Jordanian women working in two artisan workshops. Weavers-in-training at the Bani Hamida facility in Madaba for instance, follow a “recipe” with the exact number of yarn strands per piece.

“IKEA is very specific. They have to count to 248 threads for this piece,” explains a workshop manager, referring to a small black and white floor mat. The yarn used for rugs are surplus material from other IKEA products. They follow international safety standards when dying the yarns.

Women also being trained in professional codes of conduct like all IKEA suppliers. Tacked on a wall at Jordan River Foundation’s Amman workshop is a set of rules that would make most American workers rethink their day-to-day office shenanigans. (Gambling at work results in immediate termination.)

IKEA Group’s new CEO Jesper Brodin is particularly keen on creating optimal working conditions for artisans who often have very sparse work spaces. “How many hours does she work? By working so many hours in a sitting position, does she get pain in the back?,” asked Brodin who visited a weaver using a jerry-rigged loom at home. He suggested looking into the IKEA’s supplier in Vietnam who have found an ergonomic solution for their weavers.

Cactus and camels

The first IKEA collection produced by Syrian refugees and Jordanian artisans will debut in IKEA’s store in Amman this December. Called “Tilltalande,” (Swedish for “appealing” or “attractive,”) the collection includes handcrafted carpets, floor pillows and embroidered cushion covers with rather expected desert-theme motifs— camels, cacti, flirty Bedoin eyes.

The design was a collaboration between IKEA’s Sweden-based designers and local Jordanian artisans. “The co-creation of design is one very important part,” explains IKEA’s Ann-Sofie Gunnarsson who worked closely with Jordan River Foundation to develop the collection. “If we had ready made sketches, then it will not work. The artisans are really skilled and we want to learn from their process.” She explains that they scrapped their initial sketches after learning that some designs would take too long to produce.

When designing for the mass market, speed is as important as shape. “It’s really a process of finding an appealing design that is a mix of their patterns and IKEA’s global design [look], that is efficient to make.” explains Gunnarsson. The cactus motif, she adds, was inspired by a real plant growing on an artisan’s front yard.

IKEA plans to roll out Tilltalande worldwide but will consumers want these desert-themed patterns? IKEA is confident that they’ll work in all their markets—from Stockholm to Shanghai. So sure is Brodin that he’s already talking about increasing orders and scaling up production.

Brodin, who once lived in Pakistan to oversee IKEA’s regional supply chain, is banking on the symbolic charge from each handmade piece from the collection. “To provide jobs is the number one goal, of course but each product we produce together represents courage and point of view in design. This is not apologetic, this is cool,” Brodin beams, holding a pink-tasseled cactus printed throw pillow.

“This is dignity and pride and this is the type of message we want to send with the products we make.”