The decline of the large US family, in charts

Ask almost any American woman today if she’d raise nine kids and she’d likely reply, “Hell, no.” Considering the attention and expense children demand, such a proposition would seem absurd and well nigh impossible.

Ask almost any American woman today if she’d raise nine kids and she’d likely reply, “Hell, no.” Considering the attention and expense children demand, such a proposition would seem absurd and well nigh impossible.

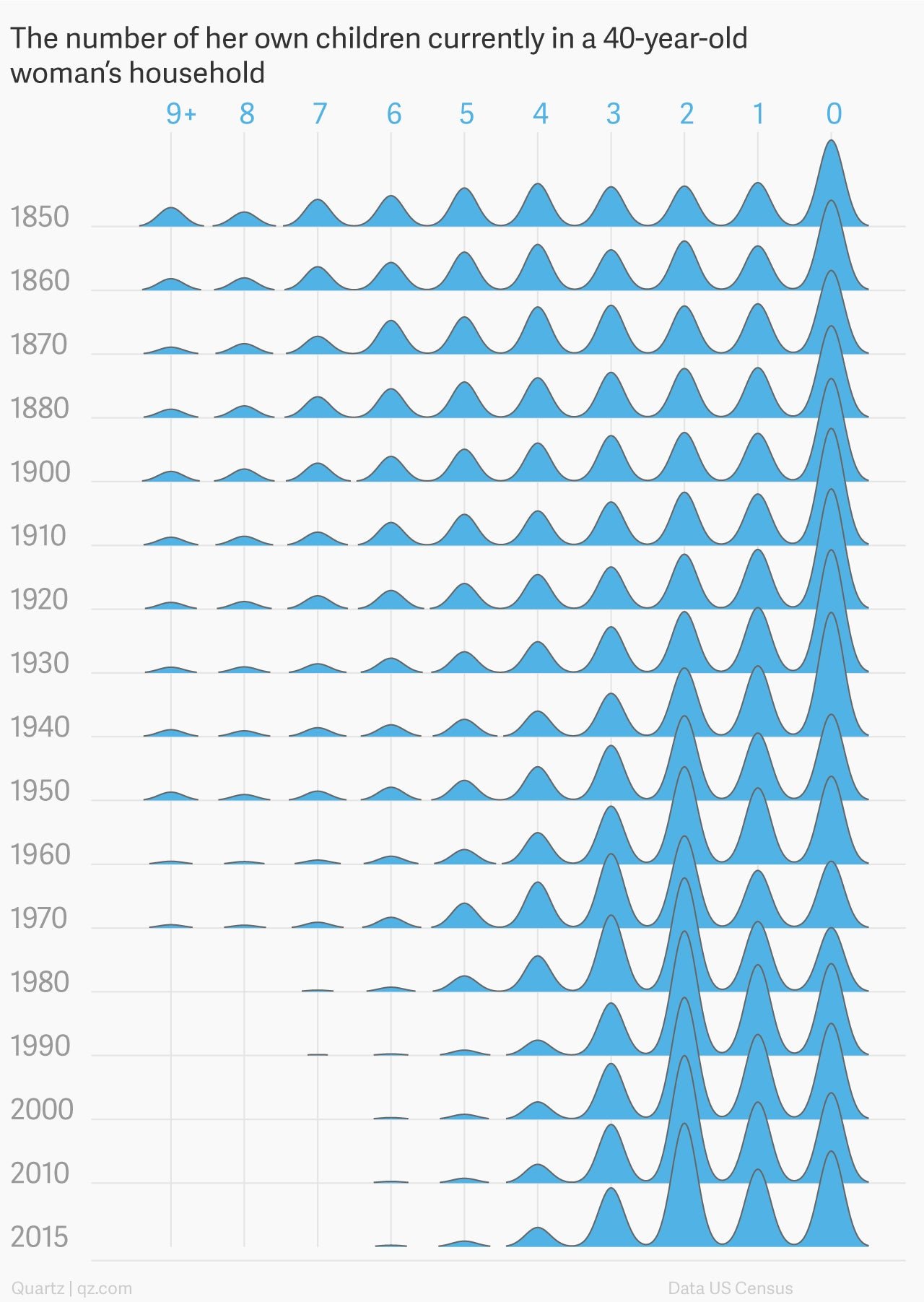

But there was a time—1850 to be precise—when huge households, chock full of tykes, were common and considered “right.” US Census data from 1850 show that families with six to nine kids were common.

One reason why was that, back then, children were considered an economic asset: with enough kids, parents could rest assured that at least some would survive and care for them in old age.

In addition, the culture dictated that a woman’s place was in the home, and her fulfillment was found there, where she served her husband and raised her children. In his 1983 book Family and Divorce in California, 1850-1890, University of Oklahoma historian Robert Griswold cited an article published in the San Mateo Gazette in the mid-19th century that states, “Woman is set in the household and man is sent out into the world.” Even a woman of modest means could “be happy in the love of her husband, her home, and its beautiful duties without asking the world for its smiles and favors,” the article argued.

Family size in the US peaked between 1860 and 1920 because infant mortality rates were declining while large families were still valued, according to Northern Kentucky University sociologist Joan Ferrante’s 1992 book Sociology: A Global Perspective.

From 1920, large American families began to dwindle. Ferrante says that American women stopped having many kids at that point due to industrialization, which created work for women outside the home and transformed children into economic liabilities rather than assets; the more kids in a family, the harder it was for a mother to go out and work.

In post-industrial America, the public perception of women changed. They went from being perceived as gentle, sentimental, and intellectually inferior to men, to being recognized as legally equal humans just as capable of voting, working, and aspiring to greatness beyond the home. Now, like men, women are “sent out into the world” to “ask for its smiles and favors.” Since gaining the world’s favors isn’t easy, there’s less time for kids and families have dwindled.

Women, Ferrante writes, began to consider their personal advancement in a new society, and that of their children. They became more strategic about childbirth. “Not only did the number of children born in the average family decrease, but the average age at which women had their last child decreased,”says the sociologist. “The mother’s median age at the time of her last child’s birth was 40 in 1850; by 1940 it had fallen to 27.3.”

By the mid-20th century, families with only one or two kids were the norm. In 1980, less than 0.5% of all households had eight or more children; that category thus ceases to appear on our chart above. In 2000, the six-child household disappeared. Meanwhile, households with two kids grew increasingly popular from 1920 on and remain common.

But things change, as the data show. Perhaps when the machine revolution begins in earnest and there are few jobs left for anyone, Americans with nowhere to go and nothing to do will have large families again and not worry about the expense.