By now, it’s clear that carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gas emissions have created and continue to exacerbate a seismic shift in the global climate. Historically, the carbon dioxide balance on Earth has been regulated in part by the planet’s tropical forests, which absorb the gas in large amounts through the natural process of plant metabolism. But humans have put so much stuff in the atmosphere that global temperatures are rising, the forests are overheating and can no longer do their job, and we’re potentially entering a cycle of climate catastrophe.

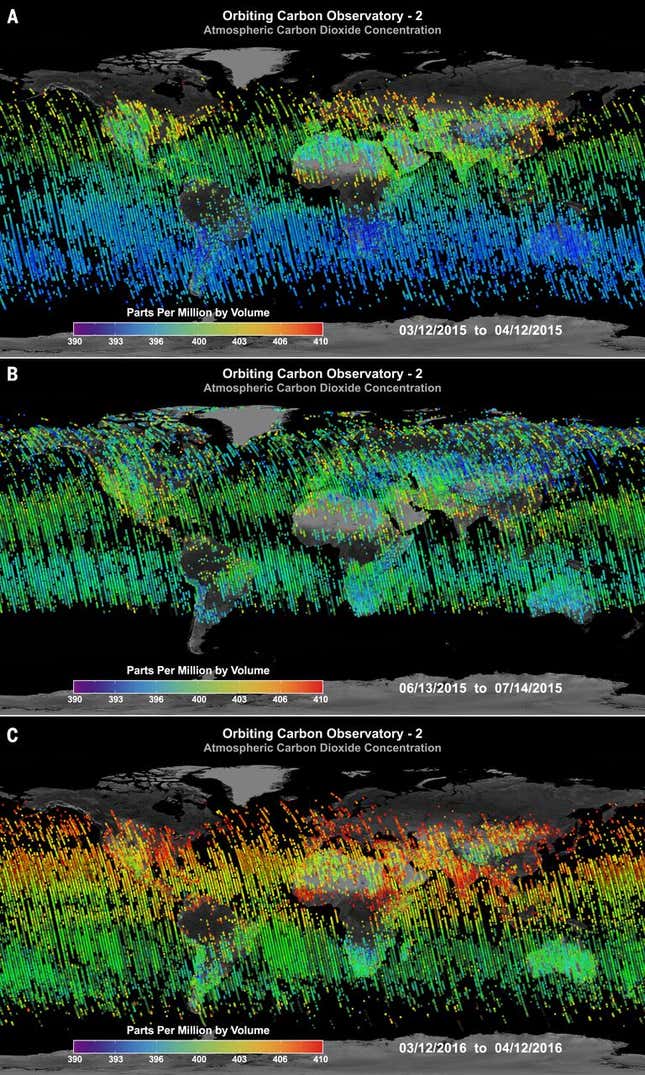

Last week, NASA announced on a press call, that one of their CO2-mapping satellites, the Orbiting Carbon Observatory, detected the largest annual rise in the amount of the greenhouse gas in the atmosphere in at least 2,000 years.

In a paper published on Oct. 13 (paywall), the scientists explained that from 2015 to 2016, the planet went through an unprecedented El Niño event. El Niño events are complex weather patterns that occur with some regularity, and have been, experts believe, for thousands of years. But the 2015-2016 version was one of the strongest in recorded history, and had an especially severe impact on the concentration of CO2 in the atmosphere.

In recent history, the amount of gas in the atmosphere has been increasing by about 4 gigatons a year. Using satellite data, the scientists calculated that in 2015-2016, the three major tropical forest regions on Earth—the Amazon in South America, the tropics of Africa, and the tropical region of Asia around Indonesia—released 6 gigatons. That’s a 50% increase since 2011, according to the study.

This is particularly troubling because scientists believed that CO2 emissions had, at the very least, plateaued. If Earth’s forests are also leaking greenhouse gases, though, we’ll need to do even more to stabilize the chemical makeup of the planet’s atmosphere. As Scott Denning, a member of the NASA team from Colorado State University in Fort Collins, said, ”If future climate is more like this recent El Niño, the trouble is the Earth may actually lose some of the carbon removal services we get from these tropical forests, and then CO2 will increase even faster in the atmosphere.”

The increase in CO2 emissions from the forests is likely due to warmer and drier conditions in the tropical forests, caused by El Niño. Those weather patterns make it more likely for plants in the tropics to dry up and rot—a process that releases CO2. And, of course, dead plants can’t undergo the photosynthesis process that removes carbon from the atmosphere.

The more CO2 in the atmosphere, the warmer global temperatures. The warmer global temperatures, the more likely it is for another severe El Niño season in the near future. More severe El Niño seasons mean more drought and dead plants in the tropics, which means even more CO2 in the atmosphere. Large-scale deforestation also certainly doesn’t help.

There are still many uncertainties around calculating our actual carbon budget—the amount by which we need to reduce global emissions to keep global warming below 2°C above pre-industrial levels (and ideally under 1.5°C). It’s a complex system with nearly impossible-to-track inputs and outputs. These new data on Earth’s tropical forests throw another wrench into the mix. But what remains clear is that if we want to leave a planet hospitable to human life to future generations, we need to act, sooner rather than later, and perhaps more ambitiously than we previously thought.