A Japanese food startup is giving high school kids meat-growing machines

Across the globe, there are eight companies making headway in producing cell-cultured meats that forego the need for slaughtering live chickens, cows, or pigs. One of the more recent entrants in that space is the Tokyo-based Integriculture, founded by chemist Yuki Hanyu.

Across the globe, there are eight companies making headway in producing cell-cultured meats that forego the need for slaughtering live chickens, cows, or pigs. One of the more recent entrants in that space is the Tokyo-based Integriculture, founded by chemist Yuki Hanyu.

Hanyu is a little bit different than his fellow travelers in the cultured meat space. For all the achievements of scientists working on these meats, no product has yet reached the consumer market. But at an Oct. 11 conference in New York hosted by New Harvest, a US-based nonprofit that supports research into developing cultured meat products, Hanyu acted like the stuff was child’s play.

“In fact,” Hanyu said with a smile. “High school students are already growing meat at home.”

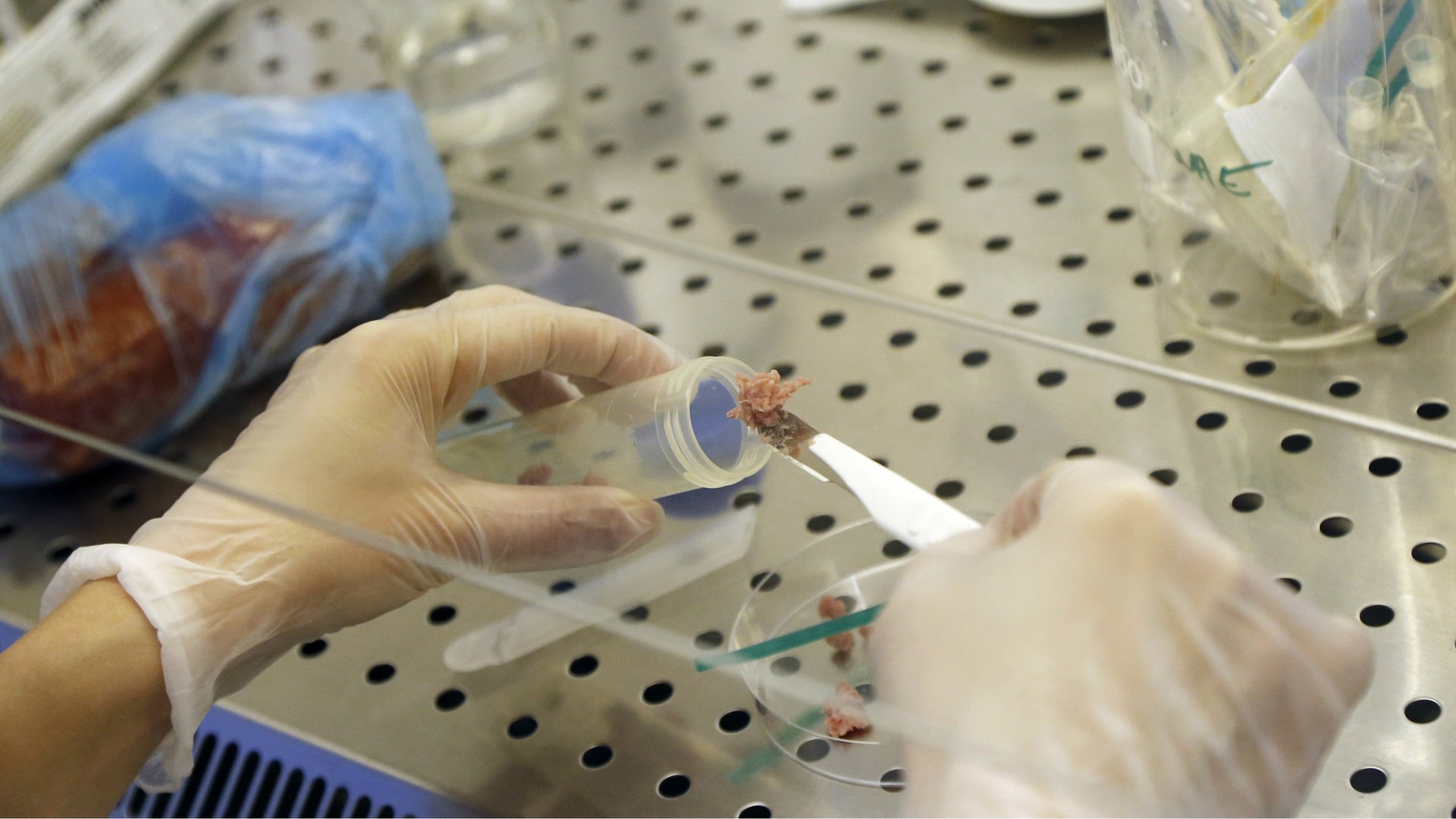

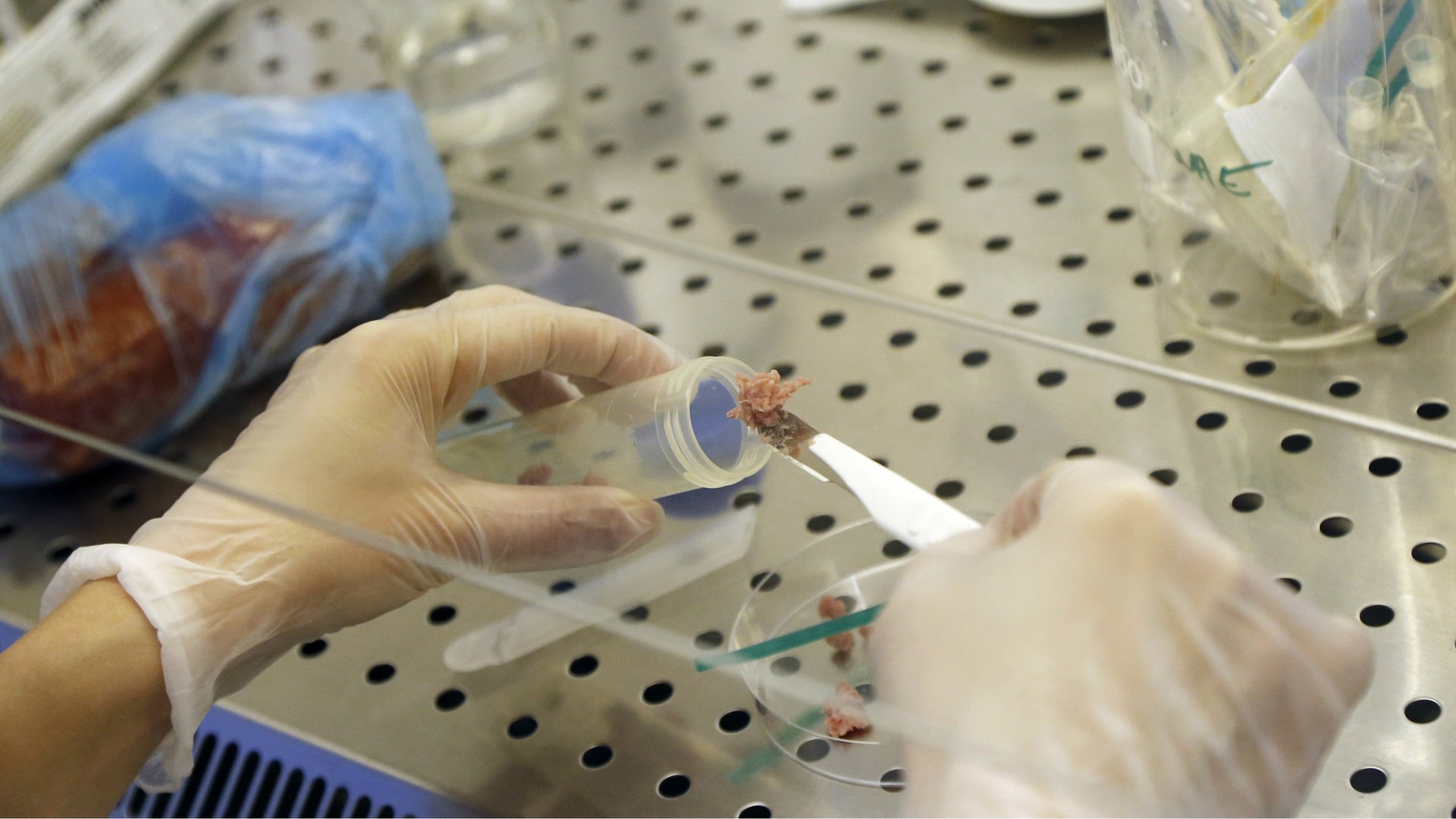

Hanyu is a singular force in the nascent industry, and it has more to do with his methods than the product he’s working to create. Through a nonprofit he’s formed, called the Shojinmeat Project, he gives students access (in Japanese) to high-tech, microwave-sized heated boxes for culturing cells in the comfort of their own homes. The students can take animal cells and grow them—sometimes in rudimentary, sugar- and protein-rich sports drinks—into slimy globs.

It may sound gross, but there’s a certain genius to what Hanyu is cultivating.

Hanyu says the GM movement fumbled in the US and Europe because the idea behind the foods—of which some consumers remain vehemently skeptical—jumped straight from academic labs to businesses, skipping over any chance for people to acclimate to the concept. The idea behind the Shojinmeat Project is to take an academic idea, engage people, and then take what he learns and apply it to future products.

The effort to work with high school students has earned his company attention and media exposure. But it’s also fostering a real a sense of educational curiosity around cultured meat, which may in turn help the products avoid the pitfalls of high-tech foods in other parts of the world.

“If they can set the direction, we will have some consensus,” he said. “If cultured meat is something primary school students can do, why would you fear that?”

It’s an approach that’s earned the respect of other people in the cultured meat space, including Bruce Friedrich, who leads The Good Food Institute, which supports and lobbies on behalf of groups working to bring cultured meat, often called clean meat, to the broader market. “I’m excited that Shojinmeat is bringing their singular way of presenting clean meat to the discussion,” says Friedrich. “Anything that makes science fun is fantastic for science.”

Still, Friedrich doesn’t think the Shojinmeat Project method is essential for introducing a cultured-meat product to consumers. “The polls that exist indicate that, right now, even before people are presented with the myriad advantages that clean meat has over animal meat, we already have half of people who are willing to consume it,” he says.

Hanyu founded the Shojinmeat Project in 2015 as a non-profit, do-it-yourself biohacker group. The group’s playfulness is unique and disarming: The group fundraises, for instance, by selling cultured-meat-related manga comic books, which include characters that appear throughout the group’s website and literature. And to figure out the best ways to introduce cultured meat to Japanese culture, Hanyu and his small team of about two dozen people (many of them volunteers) are approaching Buddhist organizations to get their input.

“Shojin means devotion to path: nonviolence, middle way, harmony, and all of those things,” Hanyu has said. “Our message is that the ongoing environmental destruction and all the unsustainable practices don’t align with this path.”

Unlike companies such as Hampton Creek, Memphis Meats, and Mosa Meat, Hanyu’s Integriculture isn’t bothering with cultured burgers and steaks. Instead, it will focus on foie gras—a liver product that has the smooth texture of pâté. The company has already submitted a patent based on its production concept. It remains unclear when a foie-gras product will be ready for market. It helps that creating a pâté-like texture requires less technological know-how than a structured steak product.