Turns out there’s a bit of Caravaggio in artificial intelligence. Also a little Vermeer, Francis Bacon, Dalí…you could even see something of Edward Hopper, if you’re looking for it. A fascinating new series of images reveals what computers “see” after being fed images and symbols from Western literature, philosophy, and history, and they’re tantalizingly familiar.

Though they may look it, these weird, vivid scenes aren’t the visions of Old Masters. They’re the hallucinations of our future masters—the product of artificial intelligence algorithms taught to create art by (human) artist Trevor Paglen, who won a $625,000 MacArthur “genius” award for his work just last week.

Artist, geographer, now genius

Even geniuses work hard. To hone his artistic practice after earning his MFA, Paglen went back to school and got a PhD in geography from the University of California-Berkeley. He has learned scuba diving in order to photograph the undersea cables that carry data from continent to continent. He has developed new photography techniques to catch surveillance planes and satellites passing high overhead, and has risked arrest to photograph secret military bases whose very existence is denied by governments around the world.

The 43-year-old’s self-directed mission is to spotlight the quiet structures of data-exchange, surveillance, and automation all around us. In his latest attempt to turn his camera on the world’s watchers, Paglen goes deep inside the automated brain, to reveal what computers see when they’re watching us, and what they dream when they’re alone. “What does the inside of the cloud look like?” Paglen said to me, describing his new show at Metro Pictures in New York City. “What are artificial intelligence systems actually seeing when they see the world?”

The installation, called A Study of Invisible Images, displays pictures that were never intended for human eyes: Archival photos used by researchers to train real computer-vision algorithms; annotated images that show how an AI processes landscapes, faces, or gestures; and the curiously baroque art generated by AI itself.

The Adams and Eves of computer vision

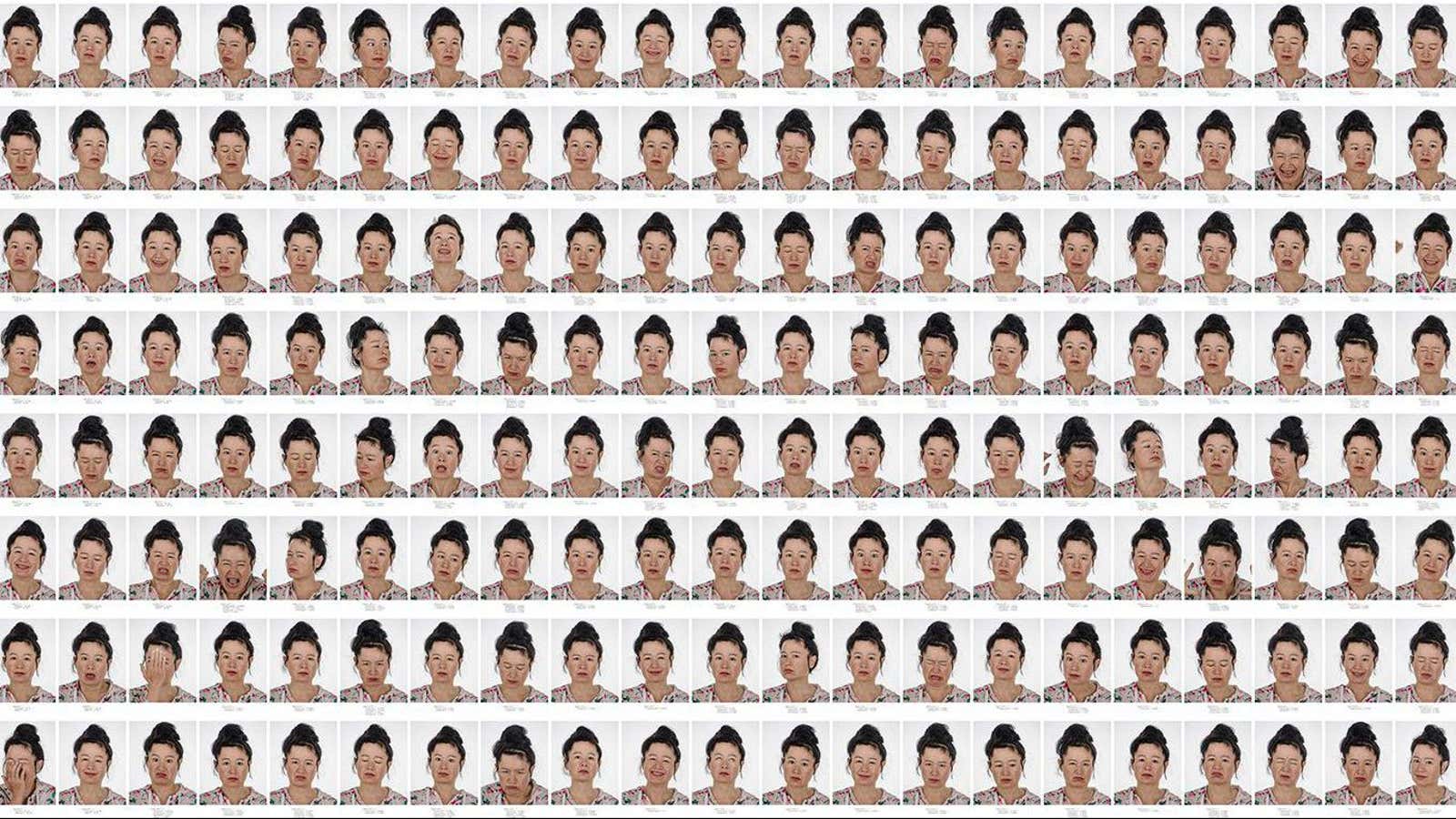

Paglen describes AI-training images as the “Adams and Eves” of computer vision. These include portraits created from the US military’s Facial Recognition Technology (FERET) program originally compiled in the 1990s to teach computers to recognize faces and foundational to the development of computer vision since then. I didn’t recognize any of them and perhaps that’s the point—shouldn’t the ordinary concerned citizen, Paglen seems to be asking, have a little fluency with the visual vocabulary of some of the most powerful automated technologies in the world?

Computer vision is already at work registering international travelers and overseeing quality control in factories. It reads the checks you deposit at the bank, captions your family photos, and tracks down criminals’ getaway cars. It does all that thanks to training-image libraries like FERET, in which the initial image labeling may have been left up to a handful of researchers with their own unconscious bias, untrained anonymous laborers on Mechanical Turk, or worse, interns.

In an essay for the New Inquiry last year, Paglen described a telling case of misidentification by a convolutional neural network (confusingly, these are often referred to as “CNN”):

Feed an image of Manet’s “Olympia” painting to a CNN trained on the industry-standard “ImageNet” training set, and the CNN is quite sure that it’s looking at a “burrito.” It goes without saying that the “burrito” object class is fairly specific to a youngish person in the San Francisco Bay Area, where the modern “mission style” burrito was invented.

It’s perhaps worth recalling the most famous “Eve” of computer vision: Lenna, a Swedish woman whose image was torn out of a Playboy magazine and scanned by engineers at the University of Southern California in 1972. With the magazine’s eventual permission, Lenna was licensed out to researchers around the world, and became an industry standard for image-processing tests. A picture of Playboy’s Miss November has since become one of the most widespread images of a woman used in computer-vision research features. This is exactly the kind of researcher-selection-bias that Paglen hopes to alert his audience to.

Computer vision is perhaps most worrying when applied to face detection. Today, in the widely used image-processing database ImageNet, photos of random individuals are still labeled “jezebel” and “criminal,” making them unwitting symbols of those concepts for who knows how long. ”What the hell is that?” says Paglen. “Who’s inventing these categories, and why are some categories in and why aren’t others? And who decides what those things look like?”

Bias is a feature, not a bug

Paglen has a full-time programmer in his studio, along with other staff. Using the custom-built platform “Chair,” which applies different machine-vision algorithms including Caffe, Tensor Flow, Dlib, Eigenface, Deep Visualization Toolbox, and Open CV, the studio is able to run its own computer vision tests, train AI on new databases, and generate images that show what the AI have learned.

In one example, Paglen turns a face-analyzing algorithm on fellow artist Hito Steyerl. In hundreds of snapshots, she grimaces, laughs, yawns, shouts, rages, and smiles. Each picture is annotated with the AI’s earnest guesstimate of Steyerl’s age, gender, and emotional state. In one instance, she is evaluated as 74% female.

It’s an absurd but simple way to raise a complicated question: Should computers even attempt to measure existentially indivisible characteristics like sex, gender, and personality—and without asking their subject? (Secondarily, what does 100% female even look like?)

Can such blind-spots in AI vision and its applications be corrected? Paglen insists that sorting the world based on looks is a fundamentally dangerous endeavor. “I would argue that racism, for example, is a feature of machine learning—it’s not a bug,” he says. ”That’s what you’re trying to do: you’re trying to differentiate between people based on metadata signatures and race is like the biggest metadata signature around. You’re not going to get that out of the system.”

Even if you could eliminate bias from machine-vision training, you might still worry about the opacity of the processes by which computer vision impact the real world. Computers already and increasingly make decisions about you—which advertisement to serve, whether or not you’ve committed a prior crime—based on vast banks of training data and image libraries basically inaccessible to anyone not already literate in machine-vision research. That could soon complicate traditional ideas of accountability: In the future, humans working with computer-vision technologies in corporations and law enforcement agencies may not themselves be capable of tracing back how an AI made its decision, much less be able to make that process transparent to consumers and citizens.

It is this invisibility of process that Paglen, who has authored books like Blank Spots on the Map: The Dark Geography of the Pentagon’s Secret World, and Invisible: Covert Operations and Classified Landscapes, seems to warn us about.

How an AI pictures human concepts

Appropriately, the AI-generated-art part of Paglen’s current show is rather dark.

To create it, the artist’s team trained AI to recognize images from databases. The images are predominantly visual metaphors or symbols, representing themes from philosophy, contemporary culture, literature, and psychoanalysis. The database used to train AI to recognize “omens and portents,” for example, includes images of rainbows and black cats, while the “american predators” database includes images of carnivorous animals and plants native to North America—as well as images of American drones, stealth bombers and Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg.

Then AI were asked to generate their own drawings of those concepts. ”We’ll have it draw tens of thousands of pictures and go through them and pick specific ones that speak to me in one way or another,” says Paglen, who adopts the role of curator to the machine-creator.

The resulting selection is dreamy and always a little bit off, with melting objects and hazy landscapes. The aesthetic isn’t accidental, says Paglen. “There is this kind of gothic, even surrealistic aesthetic that goes across all of them. That’s actually pretty deliberate on my part, like any artist trying to understand something about the moment and the political moment that we’re living in.”

An AI’s rendition of an octopus looks like something between a stalagmite and runaway eel, floating in a watery darkness. An image of A Man is faceless but familiarly so, not unlike a Francis Bacon portrait. A grey-skyed landscape titled Highway of Death is perfectly composed, and Porn seems to capture some essence of the human form.

Visitors around me started connecting what they saw to famous human-made paintings. “Caravaggio,” someone murmured. Paglen encouraged them. “This is sort of a Vermeer,” he suggested, gesturing to a glowing still-life titled Venus Flytrap.

Paglen chose to present the images like paintings, hung on deep gray walls reminiscent of the galleries of famous art museums. “I was thinking about the history of images, and vision, and human histories of seeing,” says Paglen. “By giving it a little bit of that historical aesthetic around it, I can locate it more firmly, more obviously within a history of image making. In terms of putting together the back room and that curation of images, it was very clear to me that this should feel like a messed-up version of the Tate Britain.”

Messed-up it is, but it is still surprisingly pleasurable to look at. In the end, the result is not unlike the effect of any good art on the viewer: You leave with a new way of looking at images—and a new appreciation for what they can do to you.