In a few hours from now, the night sky across urban and rural India will come to life.

The country, already in the grip of Diwali, the annual festival of lights, will break into celebrations, praying, lighting lamps, bursting crackers, exchanging sweets, gambling through the night, and making merry in general.

Though a Hindu festival, Diwali is celebrated across communities in India and by the country’s wide-ranging diaspora. On Oct. 17, US president Donald Trump celebrated Diwali at the White House, alongside members of the Indian-American community.

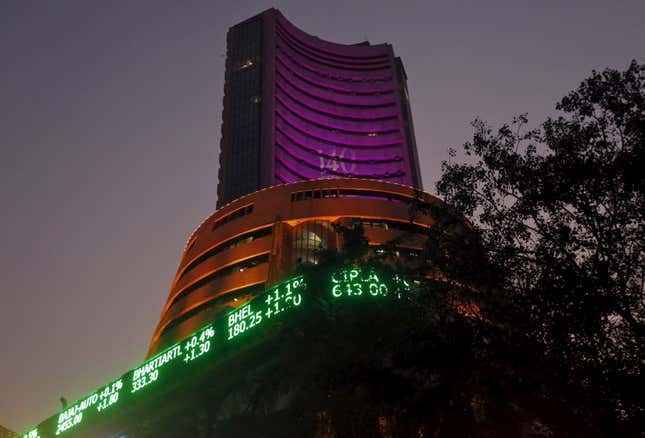

Diwali marks the peak of India’s longest festival season, which begins with lord Krishna’s birthday at the end of the annual torrential rains in August and goes on up to New Year’s Day. It is also the time that the country’s economy receives a huge boost as consumption perks up.

People splurge on clothing, gifts, food, and sweets, among other things. In fact, the four months from September to December contribute a major chunk to the annual sales of consumer durables. Every year, e-commerce majors like Flipkart and Amazon cash in on the euphoria with eye-popping discounts of up to 80% on mobile phones and ethnic clothing.

This year, though, may be a little different, for several reasons.

Reeling under major disruptions like the demonetisation of two high-value notes and the introduction of a new goods and services tax (GST) to replace the erstwhile complex web of levies, the economy is not doing all that well. GDP growth has slowed and private spending isn’t what it used to be, resulting in tough times for small businesses. A recent report by the Confederation of All India Traders, a body of around 60 million merchants, suggests that markets across the country have recorded a 40% decline in sales this festive season. However, as if it were a Diwali gift, there have been signs of a mild revival in the economy, with the effects of demonetisation and GST seemingly beginning to wear off.

Meanwhile, adding to the gloom is a temporary ban on the sale of crackers—translating into major losses for a key seasonal business—in the National Capital Region. The ban, imposed by the supreme court of India, is a measure to avoid worsening the city’s already hazardous air quality. The day after last year’s Diwali, locals in New Delhi woke up to a blanket of smog, leaving citizens as well as animals and birds choked. The revelry had led to a massive spike in particulate matter, pushing the city’s air quality index into the red zone for days, according to the New Delhi-based Centre for Science and Environment.

While other cities of the country are not affected by the ban—though they, too, are equally polluted—increasing awareness over the years has led to more subdued celebrations as far as fireworks are concerned—a trend that is expected to continue this year. In fact, a survey by the Assocham Social Development Foundation shows that Indians in other major cities want the ban expanded to their cities, too.

There are other reasons for the dampened mood. Bengaluru, for instance, is still recovering from the chaos caused by the heaviest downpour in 115 years, and traders there are complaining of a “dramatic reduction” in sales.

But make no mistake, India will still celebrate its festival of lights this year. Just a little quieter, easier, and sober.