Africa is not a country—but a continent with one billion people, living in 55 different countries, and speaking more than 2,000 languages.

Yet a relatively narrow coverage of Africa and its people exists not only in mainstream media, but as a new research paper shows, in academia as well. Virginia Tech University analyzed 20 years of research articles published in two major journals about African politics, namely African Affairs published by Oxford University and The Journal of Modern African Studies by Cambridge University.

The paper investigated whether by reading Anglophone scholarship on sub-Saharan politics between 1993 and 2013, one could actually learn more about the region’s political reality and complexity.

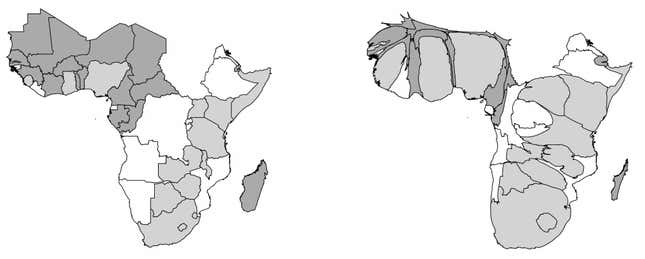

In his paper, published this month, Ryan C. Briggs, an assistant professor at the department of political science, notes that studies around sub-Saharan Africa cluster heavily on a small number of wealthier, more populous, and English-speaking nations.

Fewer than half of all the countries in the region—46 in total—were written about more than 10 times, with the majority of them being former British colonies like Nigeria, Ghana, and Kenya. Former French colonies were the focus of about 5 papers on average, while those colonized by Britain had about 27 articles written about them. Population size also mattered a lot: for every 5% increase in a country’s populace, the number of articles in every four-year period increased by about 3%.

If this shows us anything, Briggs writes, it is that Anglophone research does not represent regional politics, but rather uses “broad generalizations” deduced from specific countries to produce “a skewed image of sub-Saharan Africa” that is then applied to other countries.

Briggs doesn’t absolve himself from this practice: he told Quartz that his own work often focused on Ghana, Kenya, and Malawi. He also said that he was prompted to undertake the project after seeing how his students picked certain countries when they had to research about African politics. Testing political theories broadly, Briggs argues, will go a long way in solidifying research results and narrow the scope of generalization.

“I also think this uneven coverage matters in theory, because sometimes research ideas ‘travel’ and so something that is tested well in one place may be applied to a different place and then fail,” he said.

This bias in case selection is driven mostly by researchers who are keen on getting easy access to a country, collecting information fast, and publishing those results in good academic journals. And speaking of Sub-Saharan Africa, the term itself is also problematic—given that it is as geographically confusing as it historically loaded. Yet these biased, generalized claims are ultimately important because they trickle down from academic halls into newsrooms, social media, and ultimately into the hands of policymakers and thinkers.

One way to remedy this, however, is to engage researchers in institutions based on the African continent. In a 2016 paper, Briggs and Scott Weathers found that authors based out of the continent were more likely than those living in Africa to do specific country studies and use the results to generalize about conditions on the continent.