Shortly after Mary Jo White took the helm of the US Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) earlier this year, she vowed to usher in a new era at the agency, forcing more financial wrongdoers to admit to guilt (paywall). Today, at the very least, she was vindicated. A court found Fabrice Tourre, a former investment banker for Goldman Sachs, liable for defrauding investors after a civil trial. In fact, it found him liable for six of the seven counts the SEC had filed against him.

Historically, the SEC has allowed potential wrongdoers to get away without coming clean. Although firms and individuals often pay out material settlements, they typically agree to “neither admit nor deny” blame for the accusations.

Even though she says the “neither admit nor deny” formula will still be used in most cases (paywall), White wants more admissions. Unsurprisingly, Wall Street firms don’t like admitting that they’ve wronged investors or done shady deals, and if they have to do so, they might be more willing to take a case to court. But going to court poses a very high-profile risk for the SEC’s reputation. ”Going to trial rather than pursuing a settlement is always going to be more risky for the government,” Erik Gerding, a law professor at the University of Colorado in Boulder, told the Wall Street Journal.

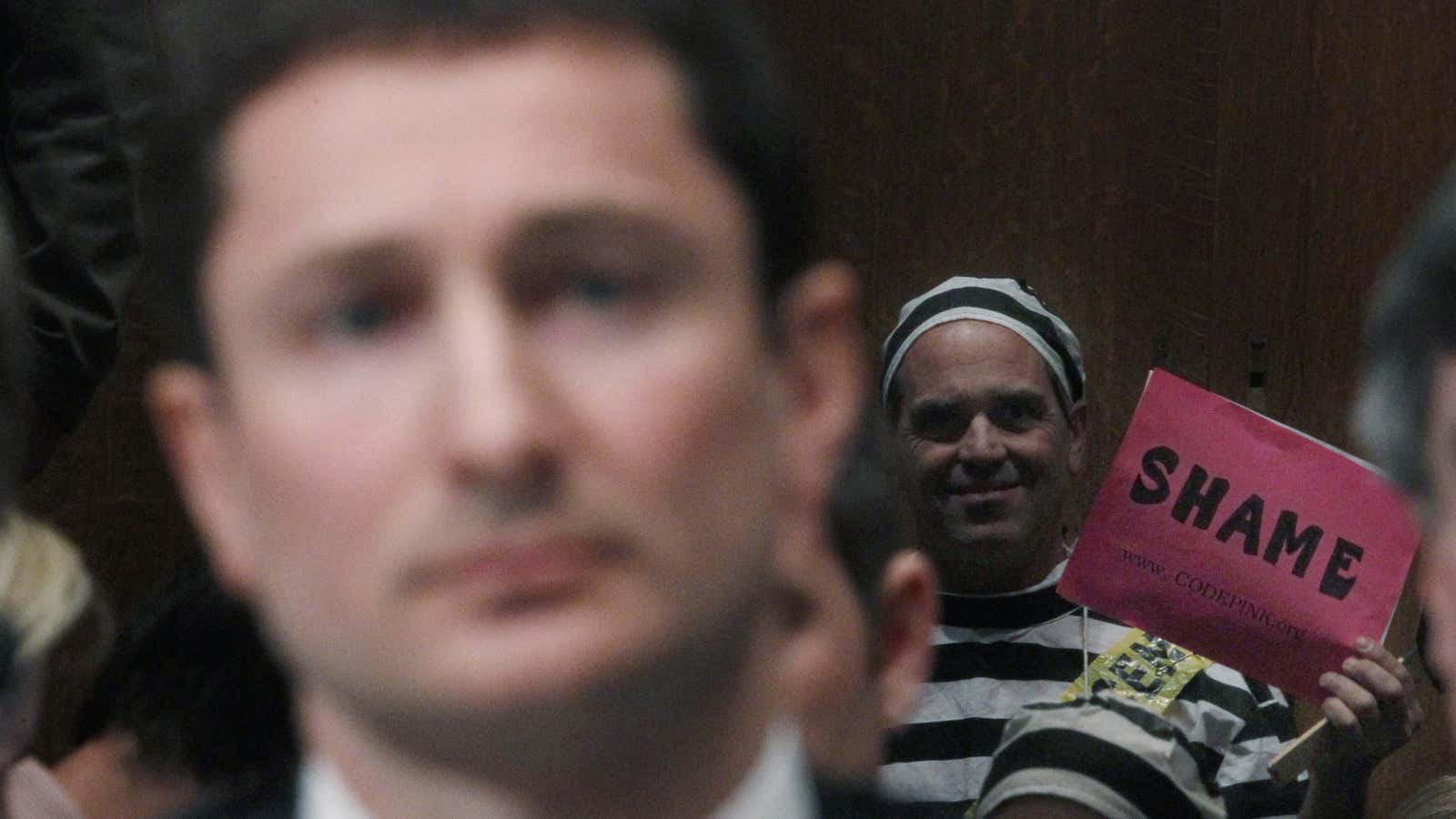

Today, at least, the strategy worked in the SEC’s favor. Tourre is infamous for emails to his girlfriend in which he called himself “fabulous Fab” and described some of his trades as “monstruosities [sic].” As such, the case has had more than its fair share of media attention.

But “fabulous Fab” was small-fry in the financial world. Now a lowly PhD student at the University of Chicago, he was a lowly vice president at Goldman Sachs—one of hundreds of 30-somethings in similar roles on Wall Street. Tourre was responsible for only a small slice of the billions of dollars in bad bets Wall Street made during the financial crisis, nor the unscrupulous ethics of the people who decided to promote the issuing of mortgages to borrowers who clearly couldn’t pay them back. In fact, his emails suggest that he was overwhelmed by the enormity of the crisis happening in the financial world.

That doesn’t mean he shouldn’t face penalties. But the SEC should consider that it has much bigger fish to fry—for instance, the high-powered executives at the top of the banking food chain. Unfortunately, those cases would be much, much harder to win.