Catalonia formally declared its independence from Spain on Friday (Oct. 27) and the central government in Madrid hit back within hours, stripping the region of all its autonomy. Prime minister Mariano Rajoy triggered the never-before-used Article 155 of Spain’s constitution and, early Saturday local time, sacked the whole Catalan government and its regional police leaders, and called for fresh local elections.

After scenes of jubilation on the streets of the Catalan capital Barcelona yesterday, the stage is now set for major tensions as Madrid starts to take back control of the region. Catalonia’s fiercely independent people won’t be ready to give in easily—their struggle for independence is centuries old, and complex. (The BBC has a handy timeline, dating back to the 9th century)

But what makes Catalonia so different from Spain anyway? We’ve taken a look at a few of the aspects of the region that make it unique, from its language, to its pioneering achievements in art, architecture, gastronomy—and human towers.

A strong identity

Catalonia has tried to sever itself from Spain many times over the centuries, and resisted attempts by Madrid to crush its culture, customs, and language. The current push for independence, however, has its roots in Catalonia’s 2006 Statute of Autonomy. Since Spain’s constitutional court overturned this statute in 2010, the regional government has tried unsuccessfully to have it renegotiated, which fueled demands for an independence referendum.

The Catalan language

Catalan is distinctly different from Spanish—that much quickly becomes clear on anyone’s first visit to Barcelona. It’s a joint-official language with Spanish, and public servants are mandated to use it. It’s also compulsorily taught in schools. In the late-1930s, dictator Francisco Franco cracked down on Catalan autonomy and banned the Catalan language. Franco ruled Spain until 1975, but the Catalans’ strong sense of identity wasn’t beaten, and the language survived his reign. Today, it is strongly tied to a sense of national identity and pride.

Surreal thinking

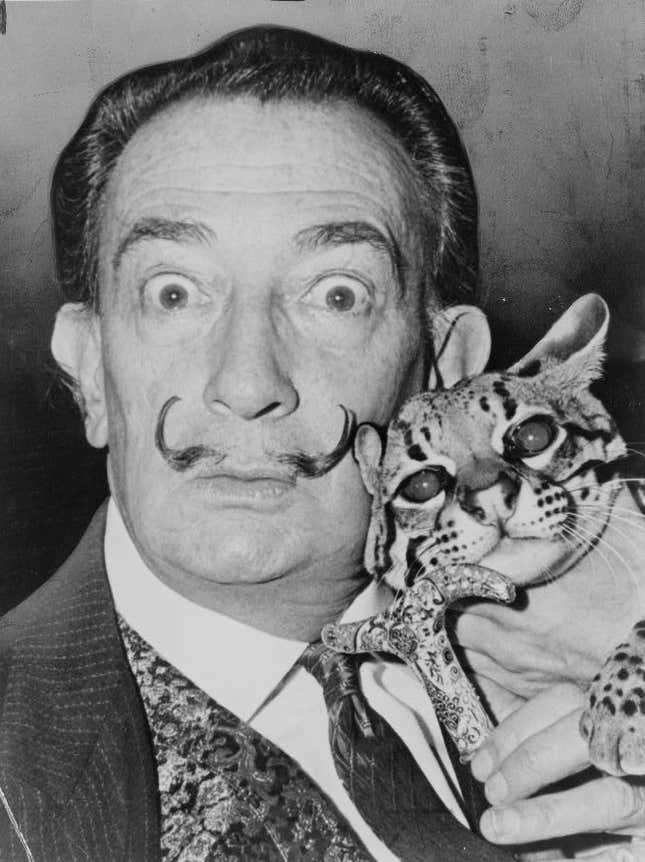

Salvador Dalí, one of the fathers of surrealist art, was born in Figueres, Catalonia in 1904. Perhaps best known for his melting clocks painting, “The Persistence of Memory,” it was a fellow Catalan artist and sculptor Joan Miró who introduced Dalí to the concept of Surrealism. Dalí’s depictions of the warped images of his dreams and subconscious shook up the art world. His outrageous appearance, with his long, curled moustache, has become as iconic as his art.

Modernist architecture

One of the key figures in Catalonian Modernism, architect Antoni Gaudí, born in 1852, put Catalonia on the map, transforming Barcelona into a capital of architectural inspiration, and massively influencing generations of designers and artists. His stunning, still unfinished Sagrada Familia basilica in Barcelona draws millions of visitors each year, and is just one of the seven Gaudi works that are on UNESCO’s World Heritage List.

Gaudí’s biographer Gijs van Hensbergen told 60 Minutes this year that what made Gaudi unique was how he saw space. “He’s someone who reinvented the language of architecture, which no other architect has ever managed to do,” van Hensbergen said.

Molecular gastronomy

Even though he is no fan of the term “molecular gastronomy,” the Catalan father of the movement, Ferran Adrià, is lauded as one of the most important chefs of all time. Half-chef, half-scientist, his development of radical cooking techniques, such as spherification—turning liquid into spheres usually using sodium alginate, so it looks like little balls of roe—revolutionized the texture, taste, and presentation of food.

It’s in part due to the Barcelona native that we have foams, vapors, sands, and bursting pearls on our plates today. Adrià’s elBulli restaurant in the little town of Roses, Catalonia, was a pilgrimage site for foodies, and regularly voted best restaurant in the world, before Adrià shut it down in 2011—but only so he could get back into his science lab and eventually open some new restaurants.

Human towers

People of Catalonia love to climb on each other’s shoulders and form huge human towers. They’re such an integral part of the local festivals that the towers, or “castells” as they’re known, also have UNESCO World Heritage status. Everyone’s invited to pile onto the human tower, and towns compete with each other as to who can form the highest one.