The first known visitor from outside our solar system has been spotted

It’s been busy month up there in space. This month began with an asteroid coming within a moon’s throw of our planetary home, then reports of more gravity waves detected at the LIGO Observatory gave researchers enough time to point their instruments at a kilonova, and now, as October draws to a close, astronomers confirmed that we’ve been visited by an object that originated outside our solar system.

It’s been busy month up there in space. This month began with an asteroid coming within a moon’s throw of our planetary home, then reports of more gravity waves detected at the LIGO Observatory gave researchers enough time to point their instruments at a kilonova, and now, as October draws to a close, astronomers confirmed that we’ve been visited by an object that originated outside our solar system.

You may call our extra-solar visitor A/2017 U1.

According to NASA, Rob Weryk, a post-doctoral researcher at the University of Hawaii’s Institute for Astronomy (IfA) was checking the sky for near-earth objects using the university’s powerful telescope on the island of Haleakala on Oct. 19 when he spotted something unusual. “Its motion could not be explained using either a normal solar system asteroid or comet orbit,” he said.

Using multiple nights of footage, and two separate points on Earth from which to make calculations by roping in a colleague at an observatory in the Canary Islands, the reason for the object’s strange orbital characteristics began to pull into focus. “This object came from outside our solar system,” Weryk said.

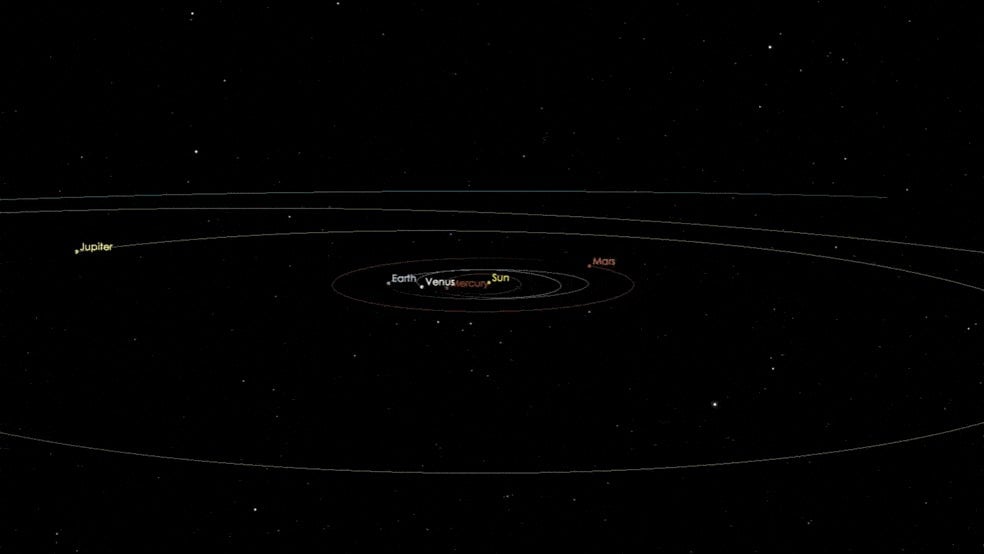

So far scientists have learned that object, about a quarter-mile (402 meters) in diameter, entered our solar system from the direction of the constellation Lyra, slingshot around the Sun back in September, and is now travelling at 27 miles per second (44 km per second) back out in the direction of Vega. Researchers think the object was ejected from a distant star system during the violent era of that system’s planetary formation, and that A/2017 U1 could have been travelling our galaxy for millions, if not billions, of years before happening on our solar system by chance.

“It sends a shiver down the spine to look at this object and think it has come from another star,” said Alan Fitzsimmons, from the School of Mathematics and Physics at Queen’s University in Belfast, who is leading an international team now studying A/2017 U1. And though the object is too far (roughly 60 times the distance from the Earth to the Moon at its closest) and far too fast to obtain samples, scientists are hoping that this opportunity may provide more insight into how planetary systems form.

Irene Pease, an adjunct lecturer at the City University of New York’s York College, who was not involved in the research, told Quartz that though it’s the first visitor we’ve seen, it’s not necessarily the first visitor we’ve had. “I would assume there are plenty of interplanetary travelers like this,” she said, “I’m assuming that we would see them only very rarely because they are very small, not particularly bright, and are only here for a short period of time.”

And whether because of providence or luck, someone happened to be looking this time.