For a futurist, Richard Watson has funny ideas about time. The British writer and lecturer teaches students, governments, and businesses “disruptive futurology,” or how to think about tomorrow, while rifling through month-old Sunday papers—in print!—skimming dated headlines.

When I met him, Watson had just delivered the keynote speech at SDL Connect, a translation technology conference in San Jose, California, in which he illuminated the future of artificial intelligence, machine learning, the internet of things, and “the convergence of everything” for an international audience of about 500 linguistic tech nerds.

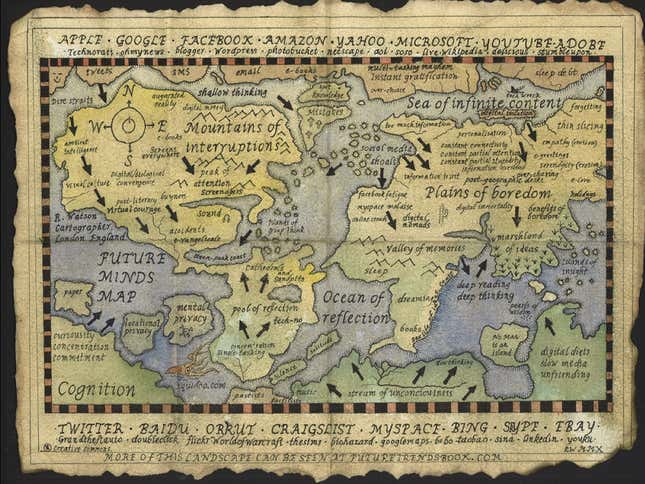

He teaches at two London business schools and is the guy Silicon Valley tech companies call when they need help imagining tomorrow. But he’s unlikely to own any of the gadgets he’s contributed to bringing into the world. Watson jealously guards his time against the ravages of tech devices and prizes disconnection from digital drains. This “Mind Map” that Watson drew several years ago and recently surfaced on his blog, What’s Next, reflects his sense of what the internet is doing to human brains.

There are too many tools and there’s too much information, says Watson, and most of us don’t know what to do with it. Watson’s job is to formulate a cohesive worldview across professions, topics, and time, so he has to read a lot. But he strictly manages intake—physical, print books get most of his time and attention. Periodicals get very little.

Watson reads the Sunday New York Times and The Atlantic in print, but only a month after publication. “It’s zen-like,” he explains of the retrospective approach, which gives him perspective. “I look backward and see if the headlines stand up to the brief test of time.” The historical view is calming, the futurist claims, and acts as a filter so only the most important things reach him.

He’ll also read online—Slate and Aeon, specifically. Still, Watson admits that he’s written letters to complain that long articles should be available in paper form. In fact, I win his confidence with my reporter’s notebook and felt-tip pen. “Paper is great technology,” he tells me. “We shouldn’t ever give it up.”

Your future to do list

Watson isn’t stuck in the past, however, and he strongly advises against nostalgia for what was. Intellectual flexibility and ferocious curiosity are keys to navigating a complicated global economy that’s in flux. Keeping an open mind, being mentally agile, traveling and meeting a wide range of people from many places, and talking to those who disagree with you, will ensure you can manage these confusing times and tomorrow, he believes.

“Don’t read crap,” Watson adds. “But also sometimes not reading anything is good for you, too.” To let information sink in and ideas germinate he sometimes spends hours or days or even weeks away from information, depending on what circumstances allow. That’s Watson’s recipe for perspective, and perspective is everything in his business. A futurist, Watson argues, needs to step back from the daily distractions. They need to understand history and contemporary trends, consider foreseeable events, and put together a big picture view.

Here’s the other thing: a futurist doesn’t have to accurately predict tomorrow.

“It’s a subterfuge,” Watson says of his “futurist” title. “It’s an excuse to have someone who thinks deeply provoke people at corporations into reflection.” Businesses are obsessed with the short term, quarterly reports, so they bring in a person who isn’t caught up in the same machinations to draw connections, prompt new ideas, and stimulate long-term thinking, he explains. In another age, Watson guesses his title might have been “philosopher” or maybe even “historian.”

But in a society obsessed with new tools, the philosopher poses as a predictor to share whatever wisdom he’s gleaned from a devotion to the old art of deep, slow contemplation. “Basically, I’m paid to disagree with people,” he says. In his consultancy contracts there’s a clause providing that Watson won’t be easy on those hiring him—disagreement is what he’s offering. “I make statements that stir conversation. It’s like lobbing little hand grenades.”