It’s a Wednesday morning in the IDEO San Francisco studio. Bright sunshine reflects off the Bay and through the floor-to-ceiling windows. But in the project space, the mood is darker.

The team is on week five of their project. They’ve been conducting tons of human-centered interviews and broad design research, and they’re writing and re-writing what inspired and challenged them. The first few weeks were an exciting whirlwind as they generated hundreds of half-thoughts: vignettes, questions, and future possibilities to throw into what they called the “idea parking lot.”

But now, the team has tears in their eyes. They are frustrated and exhausted. Post-It notes cover the walls in disordered clusters, and many lie crumbled on the ground. A stack of flip-chart pages on the floor contain sketched Venn diagrams and pyramids, remnants of attempts to wrangle the insights into a framework. The team is on edge, pointing to the clock, aware of every minute left before the scheduled call with the client. They’re not quite sure what they have learned, and they don’t yet know what ideas they would recommend. And they’re looking to me for answers.

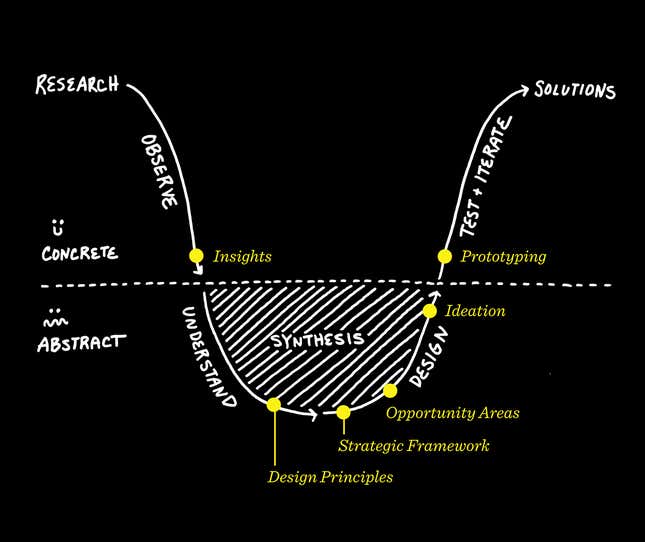

Feel familiar? This is the phase of design that gets talked about least: synthesis. It is where designers shift from the openness of “beginner’s mind” to attempting to make sense of it all. Synthesis is when things feel most unclear and unsettled, where the pressure to make new meaning from our learnings feels most oppressive.

The team knows it’s not enough to categorize observations into obvious themes. To innovate, they need to put the pieces together in new and insightful ways. They need to find a fresh mental model. And they have to imagine how this model yields a product, service, experience, or system that reframes the world in a new and better reality.

As a leader, there are few things as challenging as seeing people on your team struggle. It feels easy to offer a fast answer or a framework from your previous experience, hoping to alleviate their anxiety. But, in the end, I knew that my quick conclusions were not going to get the team creating groundbreaking ideas, and it also wouldn’t help them develop their creative muscles.

I remembered what my best teachers have done to help me through this onerous step: acknowledge how hard this particular part of the work really is, ask them great questions, and show them my confidence that they will find their way through.

In other words, I had to lead like a Constructivist.

Constructivism teaches us how we learn

One of the most difficult courses I took in graduate school focused on theories of learning. My classmates and I struggled to understand heavy academic texts, but every week we were asked to create learning experiences for each other based on these theories. Despite complaining throughout the quarter, I now realize how much graduate school taught me.

In particular, I find myself constantly referencing the Constructivist theory of learning. Constructivism, it turns out, has a surprising relationship to the design process.

Back in the 1950s, the psychologist Jean Piaget observed children to understand how people learn. He concluded that, counter to popular belief, knowledge doesn’t exist in the world, and you don’t acquire it: Knowledge exists in our own minds, through our own active construction. No one really teaches you anything, Piaget claimed. Instead, he believed that we are natural learners, constantly processing the world in order to create our own understanding.

It’s easiest to think about this theory by considering how young children learn language. Let’s say you are driving through the countryside and see a cow. You point to it and say “cow.” As the child looks, she forms a picture in her head, something like, “Ok, a ‘cow’ is big animal with four legs, and is black and white.” Later, you point to another cow, this time one that is brown and small. What’s happening in the child’s mind? Her thought process might sound like, “Wait! That doesn’t match what I understand about a cow. I thought a cow was bigger. This has four legs, but it’s not black and white.”

In that moment, the child has a choice. She can ignore you, and her mental model will stay fixed. Or, she can reconsider her understanding of a cow. Maybe cows are also brown. Maybe cows can be big and small. Piaget chose the perfect word to describe this state of misalignment: Disequilibrium.

Disequilibrium happens when you begin to see things in the world that don’t make sense to you. The things you thought you knew—the things that helped you feel stable and clear—are now in question. And, woof. This state is hard. We crave equilibrium.

To understand more, I spoke with Beth Hennessey, professor of psychology at Wellesley College. Beth is a former elementary-school teacher and now studies motivation and creativity across cultures. “Whether someone is sitting down to write a scholarly paper or trying to solve a problem in the workplace, Piaget would tell us that the state of disequilibrium is a really uncomfortable place to be,” she says. “But we don’t give up, because we don’t like being in that stage of confusion. It’s hardwired in us to create new frameworks to accommodate the information we get about the world.”

In order to bring yourself back to a calm state of knowing, you have to generate a new “a-ha” inside your mind that reframes your old information with the new information. A mental model that, through the force of your imagination and intelligence, connects those dissonant dots into new meaning.

Learning isn’t about the consumption of new information. Learning is the process of using our innate abilities to construct—or create—new understandings of the world. Learning, by its very nature, is a creative act.

Our natural process of learning is well aligned with the creative process. Design research methods—finding inspiration from diverse sources, meeting people at the extremes, finding empathy for others’ experiences—provide structured activities to purposefully shake up your understanding of a problem and put you straight into that state of disequilibrium. The approach helps you seek information that surprises you, rather than reaffirming what you already know.

We crave equilibrium. So when all this input shakes up our understanding of the world, the only way through it is to create new meaning. Synthesis is our natural creative process, and once you start to put those pieces back together into new frameworks of understanding, that’s when the new ideas start to flow.

Learning to love disequilibrium

While it is obvious that a child naturally refines and recreates their mental models of the world, we often ignore the fact that we go through this same process as adults. It is even more challenging for us, however, as our mental models have become entrenched and intertwined with our identity. It’s no longer just about understanding the word “cow”: Now it’s about designing whole new offerings, experiences, and organizations that go against the convictions that have solidified in our minds. Putting ourselves into that vulnerable state of disequilibrium becomes riskier over time, especially if we are high-status leaders.

As I’ve dug back into the Constructivist learning research, I’ve been thinking about what I am taking away from this investigation.

To begin, it takes a lot of effort to create new mental models, but we leave little room for the cognitive load of innovation, what with our endless news feeds and unrelenting inboxes. For example, while I constantly think about the time required to tick off my to-do list, I rarely evaluate how much emotional energy is required to take my work to new creative heights. I realized that I am misspending my energy. How might I more clearly recognize the areas where I’m committed to developing new solutions? How might I make space for myself to be in the challenging state of disequilibrium? How might I pace ambitions so that I’m not disrupted by too many things at once?

Hennessey doesn’t offer much comfort here. “Being in that state of disequilibrium is hard work,” she says. “If a lot of different aspects of your life are in a messy place, you’re going to struggle, because so much energy is going to need to be expended. Getting out of this state is not just cognitive demand, it’s also affective: It’s emotional.”

Recently, I found myself sitting in an important meeting, feeling frustrated and wanting to point out what was wrong. I was starting to make fast decisions and putting pressure on my team to do the same.

Then I realized that I was in disequilibrium. I was feeling stretched, insecure, and like my mental models were insufficient. I was pushing for things to make sense. So instead of getting angry, I admitted my feelings of discomfort, and asked my colleagues to help me find my way through the ambiguity. And we did.

Somehow, just knowing that you’re in that state of disequilibrium makes it feel less stressful. We can become conscious of the signals of our mental states, and we can turn them into positive feedback. For me, the signs seem to be frustration and impatience. Now, when I feel those bubbling up, I smile and realize I’m just in that pesky state of disequilibrium, and that I can be patient with myself and realize that a new state of knowing is on the other side.

Permission to struggle

It’s no wonder that my design team was in tears as they worked through the synthesis stage of their project. Their minds, hearts, and emotions were all engaged in the difficult question they were answering, and they were a vulnerable mess. They felt the pressure of time, the pressure of the cause, and the pressure of not knowing the answers yet.

As a leader, I was challenged, too. I wanted to find quick answers, be ready for the client, cut through the confusion, and get on with it. But if I had filled in the blanks for the team or pushed them to get it done fast, we wouldn’t have gotten to the depth of the design solutions that the team found over the following days and weeks. In fact, toward the end of this effort, our client who had been working in the field for 25 years said, “I’ve been working with these guys for my entire career, and I want to thank you for helping me understand them better.”

So how does this Constructivist learning theory help us support creative teams? What if, as creative leaders, we saw ourselves as great Constructivist teachers instead of orienting around our knowledge and expertise? How would Piaget’s theories change our behavior?

As good Constructivist teachers, we need to give people the permission to struggle. As Hennessy says, “Whether you’re a teacher or a manager, you need to make it explicit that you understand that innovation and creativity is hard work, that people will hit that state of disequilibrium, that people will hit dead ends, and that that is valued. The best thing a teacher can do is model their own struggles.”

Just like classroom teachers, leaders face pressure to accomplish a set of outcomes within a particular timeframe and often, unintentionally, send signals to their teams that their time messing about in search of a new mental model isn’t valid. This urgency may trigger teams to cut short those deeper, more difficult stages of creative work, leading to shallow solutions.

Years ago, IDEO developed a tool called the “Mood Meter” to help prepare newcomers for design projects. It’s a graphic that shows the journey of the design process with various levels of joy and anxiety charted on it. The idea was to provide reassurance that, although there would be some struggles, the project would end happily.

I was personally not a fan of this tool because I found it unfair to tell people how they would feel before they actually felt it. And yet, it was always right. During the research phase, people were elated, and during prototyping, too. Making stuff was always fun. But during synthesis, the phase devoted to making meaning, that line on the graph would drop to its lowest point. And that’s when you need time to sit in the struggle.

There is a belief out there that designers are constantly optimistic and confident, but that hasn’t been my experience. Creativity isn’t all about fun. Acknowledging that allows us to design better environments and processes that support the profound vulnerability necessary to develop creative solutions.

After more than a decade of leading creative teams, I believe that some of the best work comes from some of these hardest times. Confusion, self-doubt, existential searching, getting lost, and then finding your way out of that state of disequilibrium—these are the essential experiences for the emergence of creativity.