By the time his parents brought him into the burn unit at the Children’s Hospital at Ruhr University in Germany in June 2015, the seven-year-old boy was in dire shape. Over 60% of his skin was gone, and he was fighting off two types of bacterial infections.

He had a severe case of junctional epidermolysis bullosa (JEB), which is a genetic disorder in which the skin fails to make a key protein called laminin-322. Without this protein as a base, the top part of the skin, called the epidermis, doesn’t stick to the heartier base, called the dermis. As such, much of the skin (and sometimes the mucus-covered areas like the nose and esophagus) become permanently blistered and cracked at the slightest touch (warning: video contains graphic content). Hospital burn units are the specialists best equipped to deal with JEB. It’s rare—only about 500,000 patients are living with it globally, and it’s often deadly, killing about half (paywall) of people living with it before they reach adulthood.

The skin is the largest organ in the body, and has two main jobs: To hold in all of our other organs and various fluids, and to protect them from outside pathogenic microbes. Although the body can take care of most cuts or blemishes fairly well, once large portions of the skin become compromised through burns or diseases like JEB, it’s unable to fulfill these duties. Indeed, by the time doctors were treating this particular patient (whose name hasn’t been made public), they had to give him a blood transfusion every week to keep him healthy, as well as antibiotics for his various infections.

That summer, he quickly deteriorated and lost another 20% of his skin. His doctors considered him an ideal candidate for end-of-life care, and he was on a chronic morphine drip to manage his pain. A team of led by scientists at Ruhr University and the University of Modena in Italy decided to try a radically experimental treatment as a last-ditch effort to save the patient.

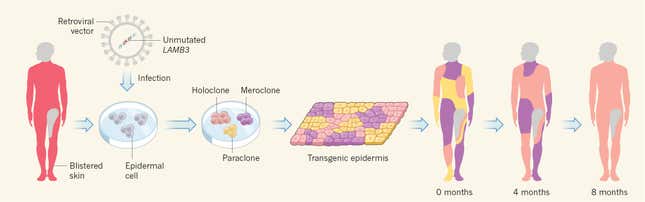

They took a tiny patch of healthy skin—just four square centimeters (0.62 square inches)—from the boy’s stomach. Then, they used a benign virus to genetically modify the stem cells within the skin to make laminin-322 and grew nearly a full square meter of the skin. Over the course of three surgeries in October and November of the same year, they grafted this new, genetically-corrected skin to his body.

Almost two years later, the young boy has made essentially a complete recovery. Because the grafts were modified versions of his own skin, his immune system won’t fight them off. Additionally, because the team modified stem cells—which are essentially the starter-cells that create every type of other cells—his new skin grows and replaces itself just like it does in healthy patients. Although the team will continue to monitor his health over the years, it seems that his JEB has been cured. A write-up of their work was published (paywall) Nov. 8 in Nature.

“The authors’ work marks a major step forward in the quest to treat disease,” Mariaceleste Aragona and Cédric Blanpain, researchers from the Lab of Stem Cells and Cancer, unaffiliated with the paper, write in an accompanying commentary.

This type of therapy is still highly experimental. The research team had to receive approvals from multiple medical ethics boards before moving forward with this patient, and part of the reason that they rushed this surgery forward was because it was the last line of possible treatment for the boy in question.The team had tried a similar approach with a patient with JEB in 2006 (paywall), but only on the patient’s legs. Although it worked, the patient still had blistering, cracked skin on other parts of the body. In the US, the only types of gene therapy that have been approved so far have been late-stage cancer treatments that modify a patient’s immune cells to attack tumor cells. There is currently one clinical trial underway in the US to see if the gene-modifying therapy is suitable for others with JEB.