Even when it’s trying to deliberately mess things up, the US Congress can’t do it properly.

Unable to reach a grand bargain to reduce America’s fiscal deficit when faced with a credit-rating downgrade in 2011, Congress legislated itself a crisis: If no debt-reduction agreement is reached by Dec. 31, 2012, politically unpopular tax hikes and spending cuts will be automatically enacted. These will reduce the debt but, according to economic forecasters, throw the country into recession thanks to a sudden lack of public and private demand. This outcome—the infamous “fiscal cliff”—was meant to be so horrible to contemplate that legislators would surely reach a deal to prevent it.

But what if flying off the cliff isn’t a big deal, at least not at first?

If the Dec. 31 deadline passes without Congress acting, a recession won’t come all at once: It’ll take time for government spending reductions to be implemented, and for consumers to notice that the government is taking more money out of their pockets and act accordingly. Those tax increases actually turn out to be fairly progressive (pdf)—a lot more so than the tax regime that Mitt Romney would like to implement as president. That should blunt their negative economic effects; and in any case most people won’t pay them until a year later.

The bigger worry is that, as the deadline approaches, markets may decide that legislators haven’t made enough progress and start selling US debt or equities in expectation of a general US slowdown. That could lead to higher interest rates on public and private debt alike, and a loss of business confidence that turns the fiscal cliff’s recession into a self-fulfilling prophecy.

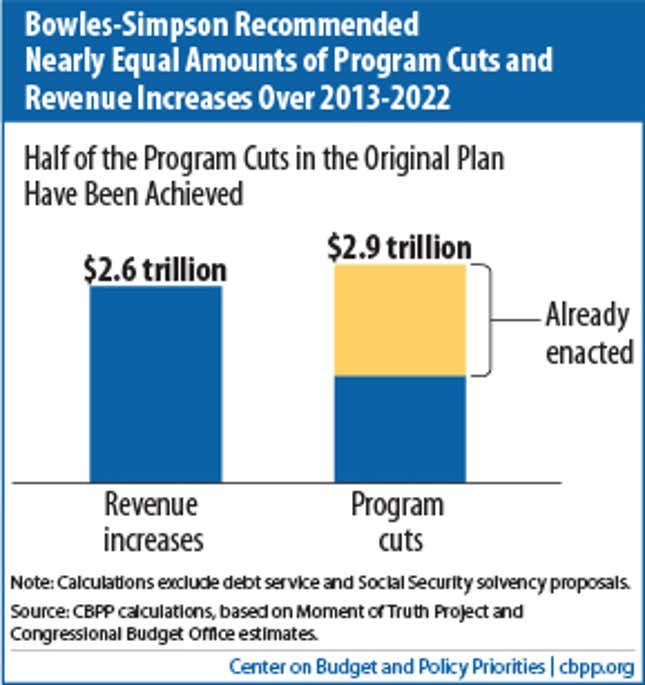

Luckily, the Solons in the Senate are already drafting a plan for a long-term budget deal. It’s based on the Simpson-Bowles report, a plan conceived in 2010 and beloved in establishment Washington as the definition of bipartisan compromise. Its central insight is simple: US spending is a few percentage points of GDP higher than usual, tax revenue is a few percentage points of GDP lower than average, so fixing the budget problem requires a mix of tax increases and spending cuts.

The challenges are two-fold. One, Republicans are dead-set against tax increases (though that may change after the election). Two, discretionary spending, especially non-defense spending, is already approaching the lowest levels seen in the last five decades, thanks to cuts implemented in the last two years, as this chart from the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities shows. There’s just not that much more room to cut; the real challenge will be refinancing the big social insurance programs whose costs are adding to US public debt.

Those obstacles are the reasons Democrats and Republicans have failed to reach a grand bargain like Bowles-Simpson several times in the past few years. But a stumble off the fiscal cliff might be a golden opportunity, as William Gale of the Tax Policy Center points out. The new tax code that comes into force would replenish revenue coffers, while giving politicians the incentives and bargaining chips to pass a fiscal adjustment that makes more economic sense—and maybe even some short-term stimulus to help delay the pain of fiscal adjustment. A new set of assumptions, the thinking goes, would make it easier for them to negotiate the thing they have spent the better part of two years failing to negotiate.

Legislators had originally hoped fear would motivate them, but even if they find a softer landing than they expected, their attempt to create a crisis may still pay off in smart policy. Maybe they weren’t so shortsighted after all.