When it comes to digging through all the money owed by the city of Detroit, which went bankrupt last month, one of the toughest figures to get a handle on is its pensions, which are either remarkably well-funded or a total mess, depending on who you believe.

The valuation of the pension fund will affect the most telling battle in the city’s bankruptcy: Retirees versus banks.

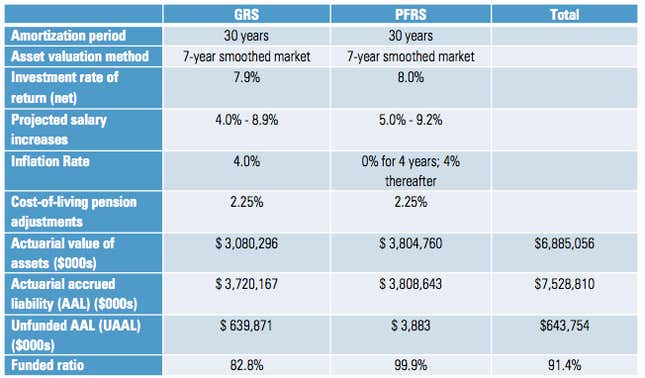

According to the city, in 2012 it was missing about $977 million from its pension fund. That might sound like a lot, but it actually isn’t bad. A breakdown of how the city got that figure isn’t available, but the table below shows how it did it for 2011, when the shortfall was only $644 million. The line that counts is the last one: It shows that the city’s two pension plans together were 91.4% funded. An 80% funding ratio generally means you’re doing OK. So even with a $977 million shortfall, Detroit’s pensions are well-funded. That’s the city’s line.

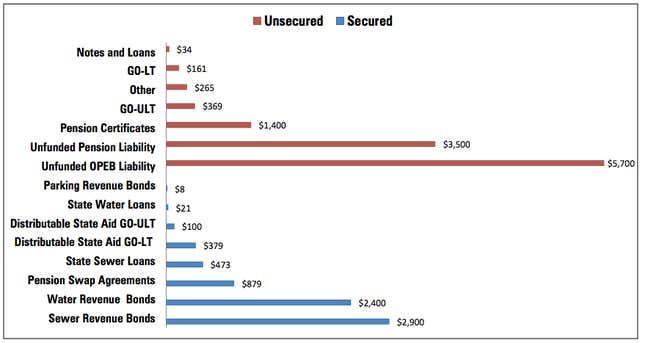

Kevyn Orr, Detroit’s emergency manager, says otherwise. The chart below (prepared by investment research firm Morningstar analysis) shows how Orr breaks down Detroit’s unsecured debt (easy to get rid of) and its secured debt (hard to get rid of):

The biggest red line, “unfunded OPEB liability,” is largely health benefits promised to Detroit pensioners. Orr has made clear that he expects that line to be wiped out, leaving retirees to scrap for new federal health-care subsidies, which analysts see as a fairly likely outcome. The next biggest is that “unfunded pension liability”—$3.5 billion, or close to half what the pension funds owe. If that’s the case, they’re in a very deep hole indeed.

Orr won’t say how his methods of calculation differ from the city’s, except that he thinks the forecast 8% investment rate of return is too optimistic. (Morningstar disagrees, saying that the city’s estimates are largely in line with industry practices. Whether or not those industry practices are particularly reliable is another question entirely.)

So why the huge gap? Orr’s assumptions may simply reflect rigorous analysis, but he might also be exaggerating the size of the shortfall to gain a negotiating advantage. One definite advantage would be that more debt makes establishing the city’s insolvency a lot easier in bankruptcy court, which is part of Orr’s job.

But a second, retirees and unions fear, is that Orr maybe simply looking for a way to reduce payments to the pension fund as much as possible in bankruptcy. Here’s how that could happen: A Michigan state law passed this year allows the governor to replace a pension’s board if it is less than 80% funded. That could mean current officials will be replaced by a board much more amenable to negotiating concessions.

And third, some investors fear a big pension deficit may make it easier for Orr to extract concessions from them too. After city workers, the largest tranche of unsecured creditors are investors who bought pension certificates when the city issued them in 2006, part of the deal that left it with such apparently well-funded pensions but also saddled it with an interest-rate swap that went the wrong way.

Negotiating lower payments for the pension certificates will be easier if Orr can cut a similar amount of money from the pensions. The difference is that cutting $1 billion from the pension certificates means a $1 billion loss for the people who own them. Cutting $1 billion from the $3.5 billion pension deficit could mean nothing if the city decides the deficit wasn’t really that large in the first place. The question turns on how specific the bankruptcy talks get over changes in pension plans and assumptions.

And a final fear for unsecured creditors: Michigan’s state constitution forbids cuts to pension benefits, even in bankruptcy. That’s a key reason why Orr moved quickly to file in federal bankruptcy court, where federal rules presumably trump state concerns. While attorneys expect the pensions will see losses in bankruptcy, it’s possible a judge could be persuaded to apply Michigan’s protection, leaving lenders to face the largest hit.