In January 2016, a company called Dinsow Robotic aired a YouTube video about Yoshii Yoshihara—an 84-year-old Japanese woman who rarely smiled or left her room at a rural nursing home. She was frail, isolated, and showing signs of depression.

Enter “Dinsow,” an elderly care robot that’s basically Alexa with a touchscreen head. Dinsow played exercise videos for Yoshii to thrash along to. It reminded her to take her medicine. It video-called her relatives. In the YouTube video, which is filmed in Japanese with selective English subtitles, the edited clips reveal a Yoshii who is laughing, gesticulating, gumming her teeth into a smile. An unnamed senior citizen across the bed from hers nods approvingly. A bubble quote appears in English: “I think she is very happy now!”

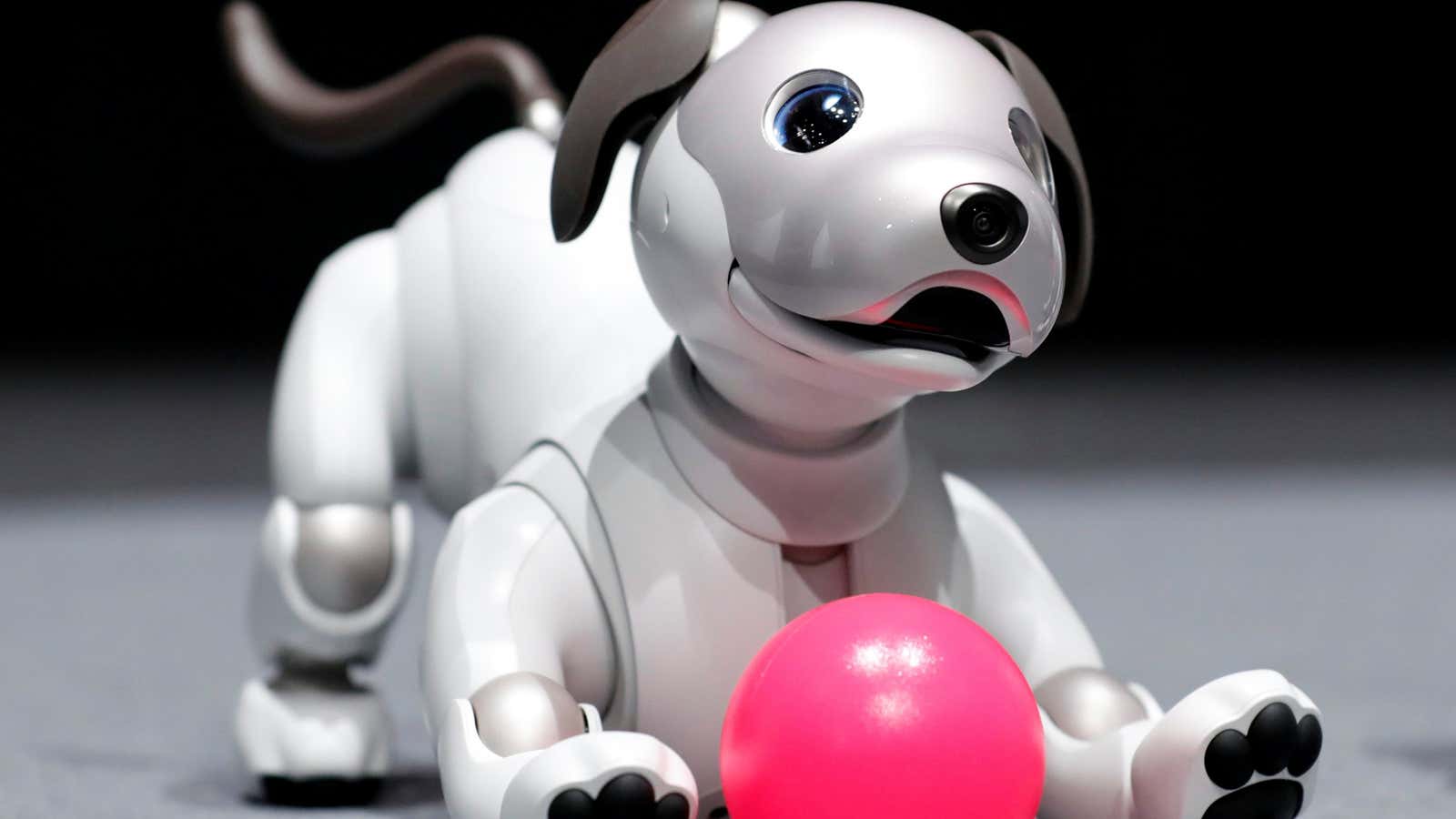

Dinsow is not the only robotic companion for the elderly. The nursing strongman, Robear, can lift elderly bodies from their beds without straining his own back. Much was made of Paro, the wide-eyed robot seal who cuddled his way into viralism when he was featured on episode eight of Master of None. A promotional video created by Alzheimer’s Australia touts Paro’s ability to provide unconditional love, companionship, and comfort to aging adults, and suggests that repeatedly stroking his antibiotic fur settles agitated elders. Via voiceover, a nursing home employee boasts that “Paro is non-confrontational, no pre-conceived ideas, and he’s there responding for as long as they want,” while a patient with dementia calmly strokes her battery-operated seal.

In an age of increasing isolation—for the elderly as well as their younger peers—robotic companions are being marketed as a way to fulfill the emotional needs of lonely humans. To date, however, much of robot design has avoided incorporating the challenging dynamics of social relationships into their products’ functionalities. From virtual assistants to robotic pets, tech companies are offering up endlessly compliant, cheerful companions that allow us to avoid the vulnerability, discomfort, and confrontation that so often accompanies our human interactions.

But perfection is rarely perfect. Not only will flawless design make it more difficult for people to tolerate friction in their everyday lives, it ignores the reality that flawlessness is … boring. Anyone who has admired Lauren Hutton’s gap-toothed smile or enjoyed their cubicle partner’s weird, infectious laugh knows that our vulnerabilities can render us more likable.

Our culture’s ongoing preference for seamless interactions has permeated the realm of pet therapy. Furry robotic companions include Hasbro’s “Joy For All Companions” robotic therapy cat; the aforementioned Paro; and Ollie the Otter, designed by MIT students. Manufactured to be hypoallergenic and easy to clean up after (read, they don’t have bodily functions), they’re also incapable of playing favorites. Paro coos for you, and only you, for as long as its battery power holds out. And Nanna can spare herself the discomfort of having to call her estranged son to feed her kitty when she goes on a cruise.

The bar is being raised in the virtual assistant industry, also, where demanding homeowners seek technology to moderate the dialogue between their smart fan and their fridge and calm their nerves as well. It used to be enough to demand that a disembodied voice play “Despacito” for the fifth consecutive time without judgment, but those innocent days are gone. Today, people want companionship from their virtual assistants. Some even want love.

Japanese engineers have already launched “Gatebox”, a holographic virtual girlfriend named Azuma Hikari who lives inside a bell jar, tearfully moderating the thermostat until her owner’s return. Hikari can text her owner, and if the Gatebox promo video is to be believed, she will do so often, growing ever more excited as day turns to night, and her internal GPS monitors her beloved’s commute home. Meanwhile, she sets his smart home environment to exactly the right temperature, orders his favorite take-out, and prepares herself to hear all about the fascinating ups and downs of his human day. She wants nothing, needs nothing, asks nothing. Like Paro, she is content to simply be there until her battery dims.

Regardless of who (or what) is on the receiving line of our affection, stripping our interpersonal exchanges of conflict can be detrimental to our social health. On a recent episode of “Note to Self,” Manoush Zomorodi’s delightful podcast about staying human in the digital age, she invited the author and psychotherapist Esther Perel to discuss the avoidant behaviors that have cropped up in the online dating world as a result of technologies that encourage us to measure our relationships in terms of their convenience. If we go on a date with someone and the sparks just weren’t there, why take the time to think through a way to communicate your disinterest sensitively when you can just disappear?

The socio-digital trends of icing, ghosting, and simmering that the episode explores permeate not just our romantic and social lives, but our professional ones as well. If common courtesies like returning emails have fallen by the wayside, you can imagine how unfathomable it is for many people to have difficult, face-to-face conversations about pay raises and promotions. Avoidance, it would seem, is the new black. Perel goes so far as to say that modern people prefer living in a state of “stable ambiguity” in which they can indulge in the comforts and consistency of a relationship without the commitment, empathy, flexibility and loss of freedom that most human relationships require.

It’s no question that real relationships are hard work. Romantic relationships, especially, are an endless exercise in micro-compromises and patience. I’m married myself, and I like to read at night, usually later than my husband, which often results in him groaning under a pillow because I still have on the light. We have learned to live with each other’s preferences, and the accommodations we make for one another aren’t always exciting. For my birthday, he bought me a LED booklight.

But making these accommodations, having tough discussions, and recognizing that always getting the preferred behavior out of our human companions just isn’t how relationships work—aren’t these the lessons that make us better prepared for life? At the workplace, especially as a woman, I’m going to encounter challenges sometimes. When a friend says something hurtful at a party, and I have to decide how to react, it’s unpleasant in the moment—but the interaction deepens my interpersonal skills.

To that end, manufacturers are now considering the benefits of imperfections as they prepare their robot fleets and virtual assistants for interaction with the human world. Toyota’s self-driving car, the Concept-i, is being programmed to be chatty—maybe overly so—with its passengers, suggesting topics of conversation when the chit-chat lags. Garrulousness might not be a trait we yearn for in virtual companions, but imbuing driverless vehicles with social desperation certainly humanizes them. Even when I would rather ride to my destination in peace, I think there’s something inherently beautiful about an artificially intelligent car who just wants to talk.

In Austria, a study by the Center for Human-Computer Interaction showed that human workers felt better about sharing their workspace with robots when the robots made modest social gaffes (asking a co-worker to repeat something, for example) or behaved like someone with a mild hangover, knocking things over and dropping items on the floor. “People who interacted with the faulty robots liked them more,” researcher Nicole Mirnig tells Wall Street Journal. “Some mistakes can make people sympathetic. It holds true for robots as it does for people.”

There is, however, a threshold for the quantity and quality of mistakes a human will tolerate from their robot friends. You probably wouldn’t be too thrilled if your driverless vehicle drove into another car, and there will be a zero tolerance for errors in the medical community, where a robotic nursing assistant dispensing the wrong medication could lead to a patient fatality—a pretty serious mistake.

Moreover, if studies are starting to show that flawed robots are appealing, that doesn’t mean that their human owners are ready to tolerate their mess. One of the earliest examples of a mistake-making lifeless companion is a doll called “Baby Alive Whoopsie Doo Doll” that peed and defecated when she was given water. If you look at the army of one star reviews for this product, you’ll find a lot of people complaining that the doll is “too much work.” I already have three kids, wrote one anonymous Amazon reviewer. I don’t need another one to clean after. In some cases, apparently, life-like is just too much life.

So where, then, are we heading with our virtual companions? Will they be designed to tolerate (or even instigate) social blunders, or will they be friction-free? Will your Roomba be programmed to “accidently” knock over a glass of Cabernet once in a while? Maybe Hikari will take an unplanned nap and forget to turn on the hallway light for your return. Or perhaps Alexa will drop a choice piece of gossip about one of your dinner party guests, and make you do the apologizing. Maybe it will be the robots who end up reminding us of the value inherent in mistakes and confrontation—the robots who remind us that empathy is the most human trait of all.