I was frustrated by newspapers’ glacial transition to the web. Now I wish we could turn back the clock.

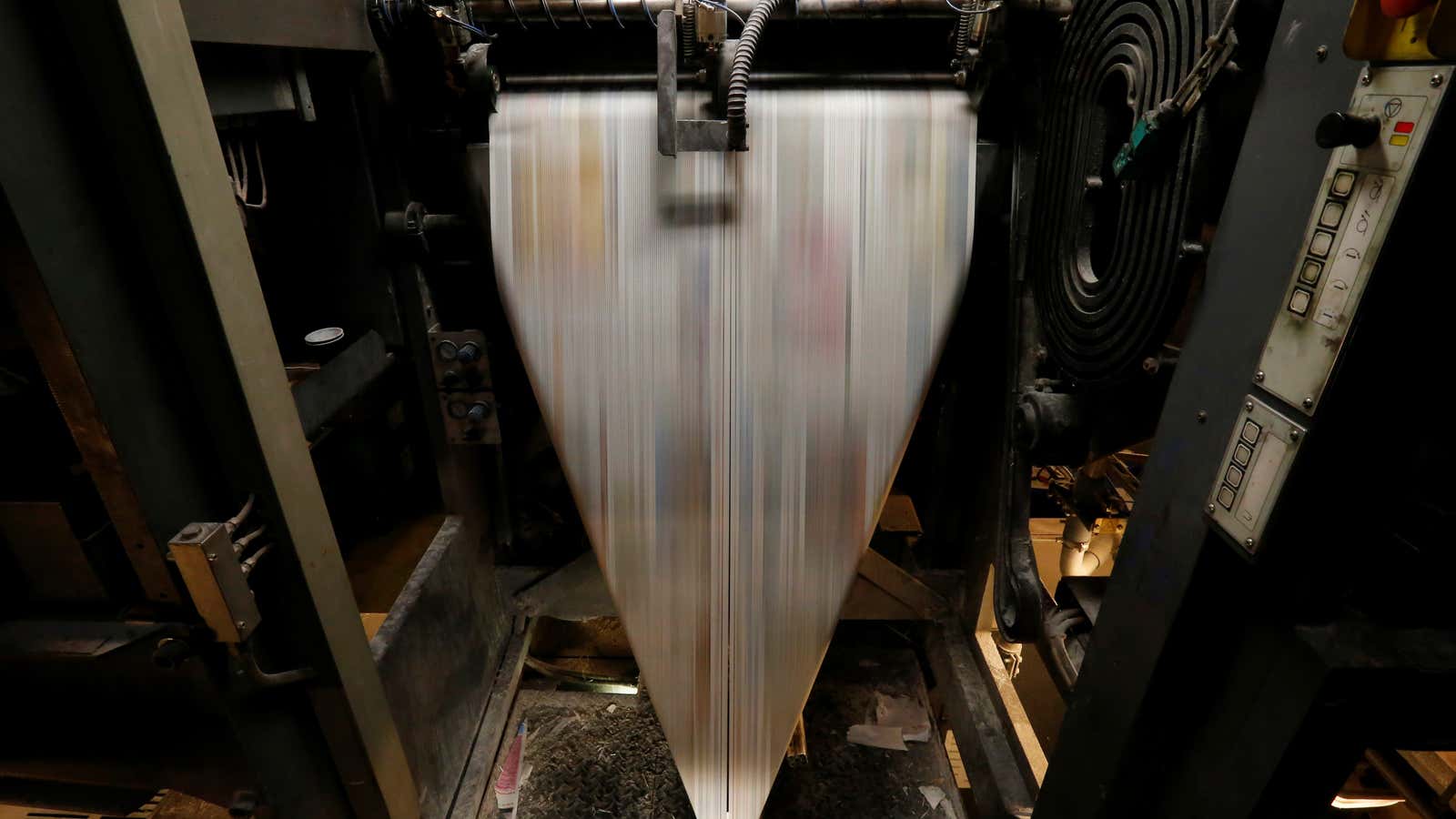

It was the summer of 2005, and I was a new college grad filled with anticipation and glee as I packed for the long trip from my childhood hometown to my brilliant, prosperous, tech-savvy future.I’d been recruited for an internship at one of the nation’s Top 20 papers, thanks in large part to a line on my resume that touted my web development skills, which had started as a hobby and grown into a series of freelance gigs in high school and college. The newspaper industry was in an uproar because of the emergence of aggressive, low-overhead, web-based competitors, and the old guard of journalism was eager for anyone who could help. My web skill set allowed me to leapfrog my peers to bigger, better job opportunities, and I was eager to join the internet revolution.This was a time before iPhones and before you could post photos on Facebook — and it’d be four more years before you could “like” something. The web department of many major papers was centered around copying-and-pasting text from the internal editorial system to an HTML page. Not only were web-based competitors like Gawker outperforming the traditional newspapers by almost every metric — including being the first to break important news — but an increase in the cost of newsprint had put a painful pinch on the papers’ bottom lines.

In retrospect, it made sense that many established journalists and editors saw the web with fear and disdain. At the time, as an overeager 20-year-old, I saw in those veteran co-workers only ignorance and an unwillingness to embrace what seemed like a welcome, positive, valuable change that would improve journalism and make the world a better place.

The result of that disconnect was several months of beating my head against the wall. I proposed rewriting our system to automate most of the stuff we were doing by hand; my supervisor reminded me it would step on too many toes. I built what I thought was a really cool Google Maps infographic, and Legal ordered my boss to take it down because they weren’t comfortable embedding content from a third party.

Still, I superficially succeeded, and within a few months I’d been offered full-time web jobs at two of the country’s Top 20 newspapers. My frustration had boiled over, however, and I rejected both offers (in one case, quite rudely) and struck out defiantly to become a self-made freelancer and technology entrepreneur.

Twelve years later, I can boil this down to two huge mistakes:

- I was an entitled, defiant Millennial — before the word “Millennial” was en vogue. While I have indeed built a solid technology career in the past 12 years, I also put myself in a position where I was broke and living with my parents in the short-term. Had I stuck with the job, I could have moonlighted as a freelancer and lived independently — the best of both worlds. That’s the exact advice I’ve given young people in similar positions now that I have the benefit of a decade of hindsight.

- I honestly believed that the internet would be good for journalism. The newspapers have indeed caught up with the competition and embraced the web in every possible way. And my prediction that it’d make the world a better place was horribly, horribly wrong.

The adoption of the Gawker, Facebook and Twitter business models and philosophies has improved newspapers’ finances, but it has put them at odds with the best interest of their readers.

Gawker and its brethren consistently humiliated newspapers in the early 2000s by beating them to big stories, taking daring editorial risks, and publishing with such frequency that it became an enjoyable pastime to just sit at your desk and refresh the page. The papers, reasonably seeking to respond to these disruptions, slowly adopted the same methods to keep us hooked and keep us clicking. I’m happy that the papers have managed to earn enough money to keep great journalists employed — but in doing so, they’ve been forced to acquiesce to a self-destructive attitude in which “more news, faster news, trendier news” is all that matters.

And they might have gotten away with it, if it hadn’t been for the explosion of mobile devices and social media.

Stop for a moment and consider the fact that 10 years ago nobody had the internet in their pocket. Today, we spend the vast majority of our lives in physical contact with a device that provides access to unlimited, unfiltered, highly addictive bursts of interesting information.

Newspapers, like everybody else, wanted a piece of that iPhone, Twitter and Facebook cash, and they embraced constant connection and social engagement. What we didn’t foresee is that social media — with its likes, retweets, comments and shares — is the most tempting and deadliest poison ever administered to responsible journalism.

We write for newspapers and magazines because we love the feeling of accomplishment when we know that thousands or millions of readers have benefited and learned from our hard work. And, if we’re being honest, we love the attention and the approval, too. The behavior of readers on social media allowed journalists to plug into what felt like a direct, immediate, intravenous injection of approval, attention and prestige. We were hooked.

The problem, of course, is that social media approval is not real. The fleeting click — increasingly inspired by a sensational, misleading headline — and the thoughtless “like” are simulations of approval, and they trigger the same burst of dopamine in a writer’s brain. They do not, however, have any correlation with a reader actually enjoying, learning, or changing anything as a result of an intrepid journalist’s carefully crafted prose, or even remembering the experience an hour later. (Pop quiz: Which articles did you “like” yesterday?) We now have an entire Fourth Estate built to reward a desperate quest for one more hit of a digital drug.

Looking back, we spent decades developing technology that freed us from limits — without taking a moment to consider whether some of those boundaries were healthy ones. In the same way your stomach, at some point, stops you from stuffing it with Big Macs, the physical limits of ink on paper kept us safe from information and attention overload.

The internet has delivered on much of its promise to improve the world. Improved communication has allowed millions of people in developing nations to become prosperous members of a global workforce, and many of my peers and I have built successful careers as we rode the wave of innovations that we were lucky enough to adopt as kids. New technology saves and improves lives every day.

However, when it comes to the internet’s effect on journalism and the effect of information overload on our brains, technology has been, at best, a double-edged sword of anxiety, confusion and overwhelm.

If I could jump in the DeLorean and intercept my 20-year-old self, I’d tell him to take that job. I’d tell him to embrace those veteran journalists, taking a stand for news that is thoughtful, calm and reserved. And I’d tell him to reject a culture that whiles away its hours gawking at the next scary, controversial, fleeting flash of stimulation.

Instead, I doubled down on the web and eschewed my colleagues whose decades of experience gave them an early glimpse at its hypocrisies, dangers and flaws. Like me, the newspaper industry dove head-first into the wonders and perils of a sea of infinite information.

Here’s hoping we all find a way to stay afloat.