Human rights lawyers feared the worst, but the US Supreme Court seems inclined to retain a law that is used to isolate some of the world’s most brutal nations by punishing global companies working there, court watchers say.

The US high court heard arguments Oct. 1 involving a suit against Shell, the Anglo-Dutch oil company, for allegedly aiding and abetting torture and execution in Nigeria.

For the last three decades, one hazard of oil drilling, mining, and other business in the world’s badlands has been getting sued in the US for the heinous acts of the host government. The Shell case is among some three dozen suits currently under way against corporations under the Alien Tort Statute, which allows claims of a “violation of the law of nations or a treaty of the United States.” The law was passed in 1789 but got little attention until the 1980s, when human rights lawyers began applying it as a way to exert economic pressure on dictators.

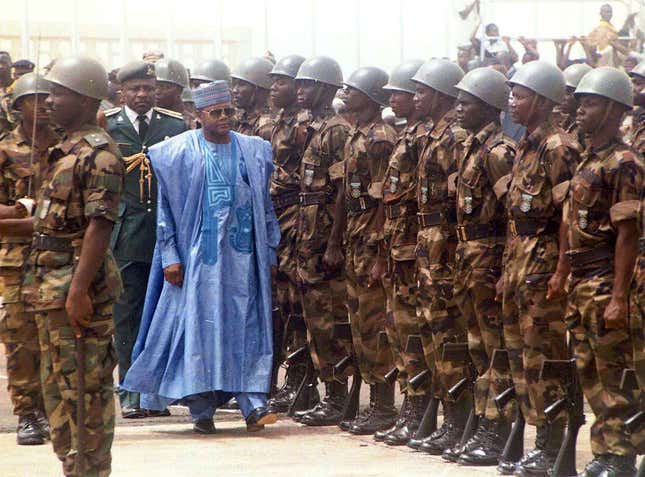

Shell challenged the law after being sued by a dozen Nigerians asserting that it was complicit in heinous acts in the 1990s by the Sani Abacha regime. The Supreme Court originally heard the case in February, but the justices got so exercised over the idea of liability for acts committed abroad that they summoned the lawyers to explore whether such suits should be banned outright.

Experts noted that such re-hearing of oral arguments has preceded some of the court’s most far-reaching decisions, including the 1954 case banning segregation in schools and the 2009 decision allowing anonymous political contributions. Human rights lawyers had forecast an evisceration of the law, while corporate lawyers had hoped for the dismissal of many of the current cases.

In the Shell case, some of the clients have been awarded asylum in the US. But Shell’s lawyer, Kathleen Sullivan, the former law school dean at Stanford University, claimed that no suits involving conduct abroad should be permitted, not unless Congress decides to go back and say so. But she got serious pushback, while the justices seemed “surprisingly easy” on plaintiffs lawyer Paul Hoffman, said Martin Flaherty, a professor at Fordham Law School, in an interview.

Many of the justices suggested that they were inclined to respect a landmark 2004 case that allowed suits alleging violations of norms having “acceptance among civilized nations,” such as 18th century-style piracy. Sullivan had argued that even piracy is no reason to allow a suit, but Justice Stephen Breyer suggested that the pirates of the 18th century are analogous to torturers today. “If, when the statute was passed, it applied to pirates, the question to me is, who are today’s pirates?” Breyer said. “And if Hitler isn’t a pirate, who is? And if, in fact, an equivalent torturer or dictator who wants to destroy an entire race in his own country is not the equivalent of today’s pirate, who is?”

“The justices appeared to be surprisingly easy on Paul Hoffman, who was arguing in favor of the human rights victims, and instead seemed to attempt to find the proper theory and limitations on classic Alien Torts Statute suits,” Flaherty told me in an email exchange. “Conversely, Kathleen Sullivan faced pointed questions from justices across the spectrum.” Flaherty said the oral arguments suggest that the justices do not appear eager to rule out suits for alleged violations abroad.

An indication of what might be coming was suggested by Solicitor General Donald Verrilli, who urged the court to ban only suits alleging that a corporation aided and abetted a heinous act abroad, but did not commit the violations themselves.