A Taiwanese democracy activist is sent to prison in China for his social media activity

A Chinese court today (Nov. 28) sentenced Taiwanese human-rights activist Lee Ming-che to five years in prison on charges of subverting state power, an unsurprising end to what critics have called another sham trial in China.

A Chinese court today (Nov. 28) sentenced Taiwanese human-rights activist Lee Ming-che to five years in prison on charges of subverting state power, an unsurprising end to what critics have called another sham trial in China.

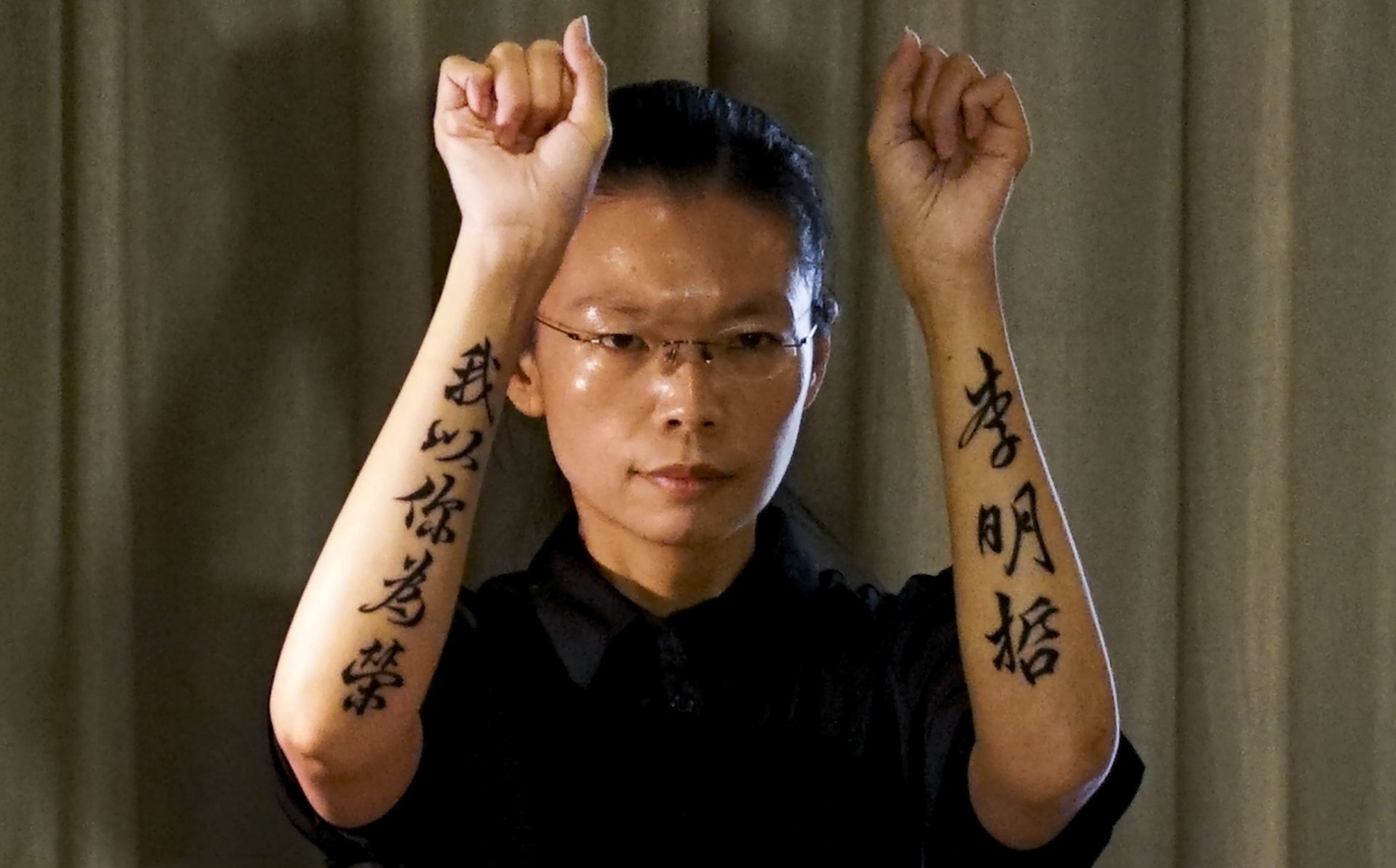

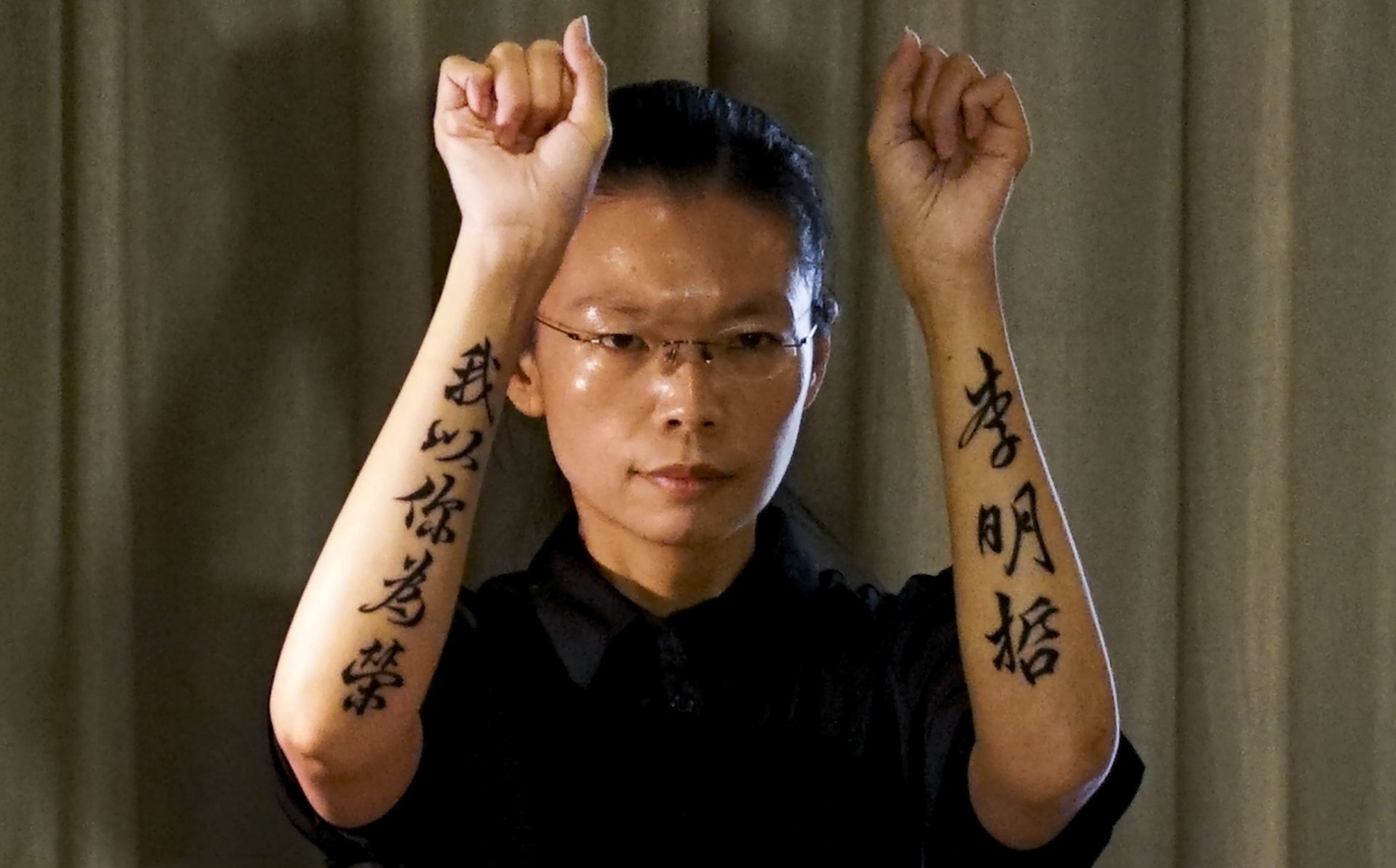

Lee, 42, who worked for organizations advocating democracy and human rights in Taiwan, went on trial in Hunan province in September after 170 days in detention, during which he was not allowed to see his family and had a lawyer appointed by the court. He was arrested when entering China in March.

He pleaded guilty to charges of subverting state power by promoting Western-style democracy using online messaging groups, and said that he had been misled by inaccurate portrayals of China in Taiwanese media in the past. With forced confessions a common feature in China’s judicial process, Lee’s wife told the Taiwanese public earlier that any such confession given by her husband could only be given under duress. Mainland Chinese activist Peng Yuhua was tried alongside Lee, and pleaded guilty to similar charges. Peng on Tuesday was sentenced to seven years in prison.

The case is the first time a Taiwanese citizen has been charged for subversion of state power in China, but Lee’s ordeal also underscores the unique dangers for Taiwanese citizens in China, as China claims Taiwan as its own territory. The Taiwanese government has said that others of its nationals being held in China have had their rights curtailed, despite an agreement struck by the previous Beijing-friendly administration in Taipei that Taiwanese held in China should be allowed such rights as access to family members.

Taiwan’s presidential office called the verdict “unacceptable” and “regrettable,” and said the handling of the case has hurt relations between the two sides. It urged China to release Lee as soon as possible. Jerome Cohen and Yu-Jie Chen, experts in Chinese law at New York University and Columbia University, respectively, wrote earlier this year that Lee’s past affiliation with the current ruling party of Taiwan, the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP), may have been particularly problematic in Beijing’s eyes as the DPP advocates Taiwanese sovereignty.

Patrick Poon, a researcher at Amnesty International in Hong Kong, however, said that Lee’s case is not just a warning for Taiwanese citizens engaged in human-rights work or other issues deemed sensitive to Beijing, but for any foreigner working for a nonprofit in China. The country this year enacted a tough new law against foreign non-profit organizations, subjecting them to extra scrutiny if they want to continue operating in China. Given China’s vague definition of “subversion,” any foreigner doing such work could potentially be a target.

The verdict also underscores the dangers of sharing information on Chinese social media, including via what may appear to be closed-group chats. The chats included discussions of the 1989 Tiananmen Square student protests, according to Amnesty, a particularly taboo topic on the mainland. The indictment also mentions Lee’s activities on Facebook, the rights group noted in a statement last month, although the social media platform isn’t accessible in China.