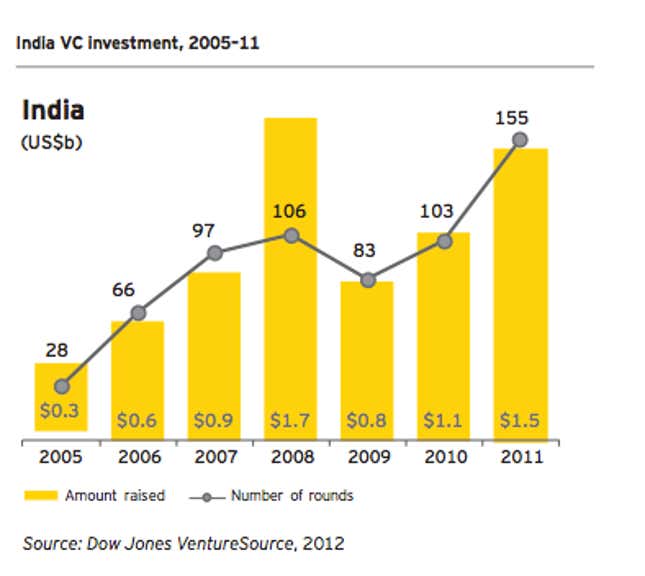

Only a decade old, India’s venture-capital industry is already one of the biggest in the world. But a symptom of its youth is that the money is unevenly distributed. While total venture investments have quintupled since 2005, reaching $1.5 billion last year (pdf) according to Ernst & Young, almost all of that has gone into mid- and later-stage startups. Angel investors, who support the truly fledgling businesses that haven’t yet developed a market and revenue stream, number fewer than 500 and allocate just $22 million a year, according to a government count (pdf, 35). By contrast, in America, hundreds of thousands of angels invest over $20 billion a year, according to estimates by the Center for Venture Research at the University of New Hampshire.

So a proposed tax on angel investments was of particular concern to those who gathered in Delhi last weekend for TiEcon, a global entrepreneurs conference. One side-effect of the flood of later-stage funding, Ernst & Young says, is to push up valuations; and it can also inflate expectations for younger companies that haven’t yet raised the extra cash they may need to negotiate convoluted bureaucracies and infrastructure gaps. A tax on angel investments would make that problem even worse.

India is one of the toughest places in the world to launch a company, ranking 166 of 183 in ease of “starting a business,” according to the World Bank’s “Doing Business” survey. For the ecosystem to mature, the state needs to support innovation and help to slash startup costs much earlier in the process, a government committee suggested (pdf, p 34) in June. It urged the public sector to boost funding for startup incubators and for hard infrastructure, to clarify intellectual property and labor laws, and to offer banks and investors incentives to lend to and invest in new ventures.

Indian entrepreneurs have often resisted state intervention, and many dismissed the committee’s June report as wishful thinking. But public sector efforts to promote entrepreneurship have been tried elsewhere, from Israel to Chile to Poland. Some of those initiatives have required billions in state cash; but India could start on the cheap by streamlining permitting procedures, enforcing contract law and easing regulations on early-stage investing. As environmental risks ease, private investors are more likely to accept the risks associated with funding the kind of transformational ideas that the scene needs.