You’re nice. You don’t enjoy others’ suffering, except of course when they’ve done wrong and you want them punished for the transgression. Maybe you’d even pay to watch that justice meted out. That desire is apparently natural in humans and animals, and it starts pretty young.

Small children and chimpanzees are gleeful when they see just punishment for antisocial behavior, according to a study published Dec. 18 in Nature Human Behavior (paywall) by researchers at the Max Planck Institute for Human Cognitive and Brain Sciences in Leipzig, Germany. “When misfortune befalls another, humans may feel distress, leading to a motivation to escape,” the study explains. “When such misfortune is perceived as justified, however, it may be experienced as rewarding and lead to motivation to witness the misfortune. We explored when in human[s]…such a motivation emerges and whether the motivation is shared by chimpanzees.”

Checking the motivation of chimps, the researchers thought, would show them if the behavior was purely a function of human socialization or could have biological roots. The interest in seeing justice meted out could have evolved across creatures who live in groups to protect community.

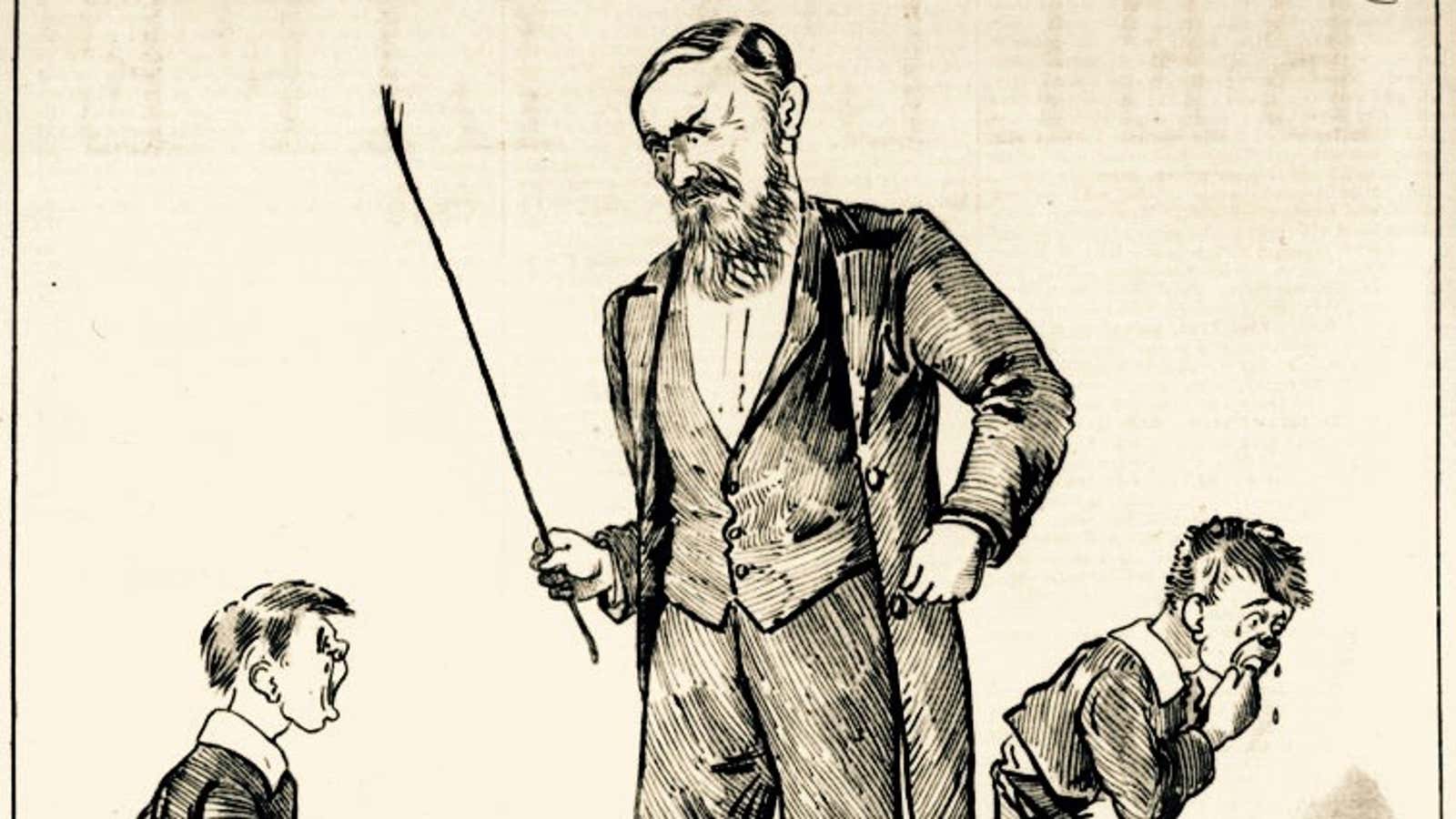

Indeed, the scientists discovered that pleasure in just punishment emerged at age six in kids and was also present in chimps. The two groups were more interested in just punishment of antisocial behavior—in this case, beating a puppet or person who deprived kids or chimps of their toys or food—than in receiving awards themselves. And they were willing to pay in coin or make an effort to watch a beating. Both groups also showed glee when watching a bad guy suffering. On the other hand, younger children, the four- and five-year-olds, did not respond positively to just punishment.

To test kids’ motivations, the researchers put on a puppet show with two characters, one good and one bad. They interacted with the young audience, asking to take their toys and, if bad, refusing to return them. A third character then joined the show to punish the first two puppets.

Kids could then choose whether to use a coin they’d been given to watch the good or bad puppet get punished or to pay for stickers. The kids didn’t want to see the good puppet punished, generally speaking, and young kids weren’t interested in seeing justice enacted on the bad puppet. But the six-year-olds paid to watch the bad puppet get hit and wore gleeful expressions all the while, say the researchers.

To test whether chimps would respond similarly, workers at the Leipzig Zoo played the role of good and bad puppets, and a similar study was conducted over the course of several days. But instead of giving and taking toys, the good and bad zookeepers gave and took food. A third person then joined the drama and tried to beat the good and bad people—to see this punishment enacted, the chimps had to really look, pushing past a door to another room. This exertion was equivalent to paying in coin for the kids.

When it came time to punish the bad zookeeper who deprived them of food, the animals were eager to make an effort to go see the person get hit. Many of the chimps protested vocally, however, and some also turned their backs so as not to see when the good zookeeper who gave them food was being punished unjustly.

“Both six-year-olds and chimpanzees have a motivation to watch deserved punishment enacted,” the study concludes. The researchers believe that this sense of social justice, which in kids seems to develop at age six, is a biological mechanism that evolved for social control in communities.