“Although poor, my father was dedicated to educating his children and we were practically the only literate family in the village inhabited by about 100 people.”

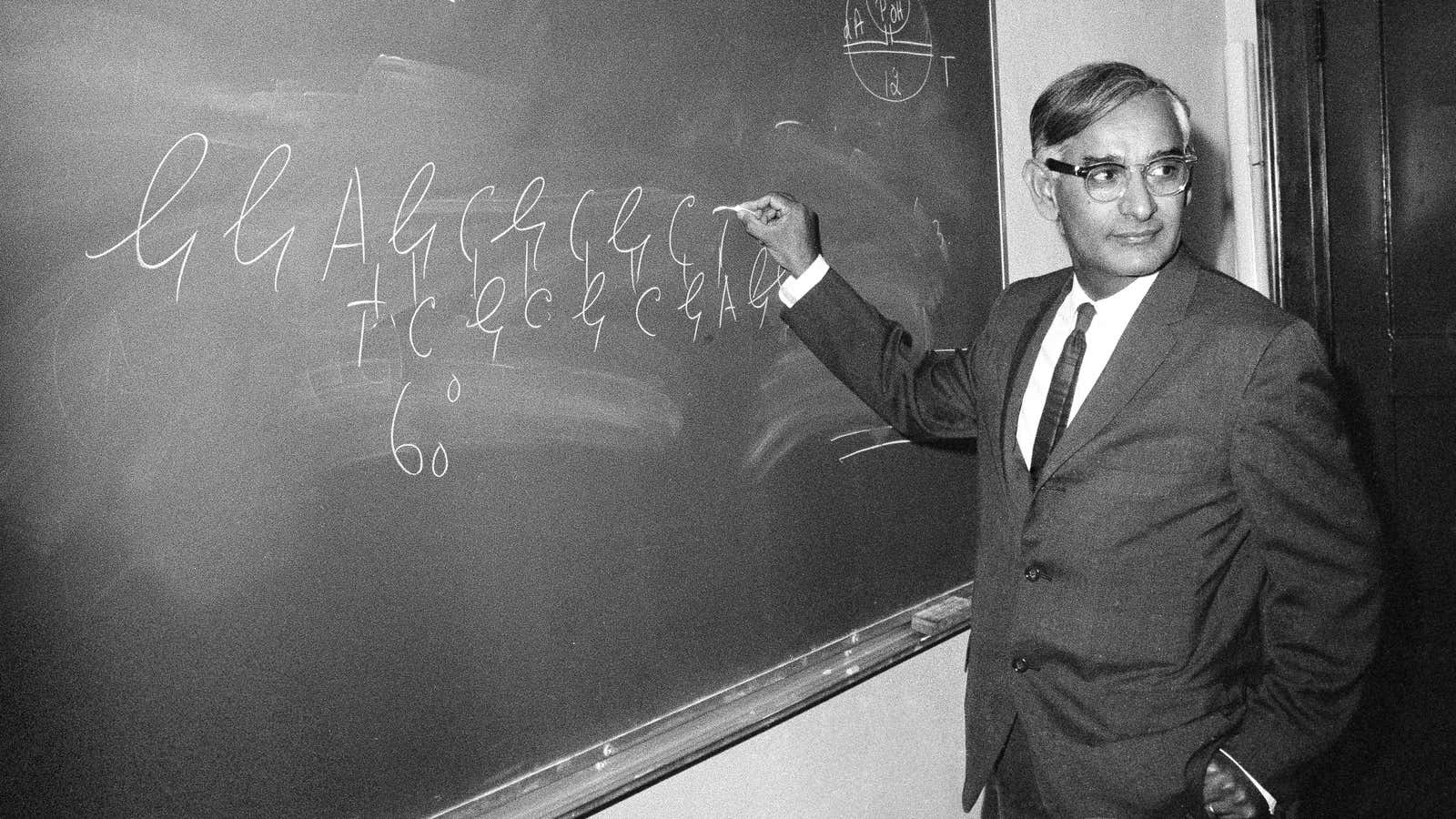

These were the words Har Gobind Khorana wrote to describe his childhood when he received the 1968 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine. His father’s commitment, Khorana believed, springboarded him out of poverty in India to become a beloved giant of the scientific world.

Today (Jan. 9), on what would have been Khorana’s 96th birthday, Google’s Doodle in 13 countries honors his work and life. His scientific contributions developed our understanding of genetic material and laid the groundwork for the modern field of biotechnology.

Khorana’s biggest contributions

Khorana’s first major breakthrough, for which he was awarded the Nobel, was for decoding the genetic alphabet and demystifying its role in protein synthesis. Through his experiments on nucleic acids—the lettered molecules that make up our genes—he unambiguously confirmed that the genetic code is composed of 64 distinct three-letter “words” that dictate the order of amino acids in proteins. He shared the 1968 prize with Robert W. Holley of Cornell University and Marshall W. Nirenberg of the National Institutes of Health, who each independently contributed to the groundbreaking discovery.

In 1972, Khorana made a second breakthrough, constructing the world’s first synthetic gene. Four years later, he made another leap forward by injecting the gene into a living bacterium. His tiny engineered organism blazed a trail for the manipulation of life through its most fundamental building blocks and helped lead to critical advancements in the biological and medical sciences. These include the ability to create artificial life and most recently, to edit genomes with CRISPR technology, which could one day eradicate genetic disorders.

His formative years

Throughout his famed career, Khorana never lost touch with his modest beginnings, which infused him with a sense of humility that was admired by his colleagues. He was born the youngest of five to a Hindu couple in the small Punjabi village of Raipur, India (today part of eastern Pakistan), and spent the first 23 years of his life in that country. His actual date of birth is unknown but is shown in documents as Jan. 9, 1922.

Early on, with his father’s encouragement and his village schooling, Khorana demonstrated an aptitude for science. This earned him a full scholarship to study chemistry at Punjab University in Lahore, despite skipping the mandatory admissions interview because he was too shy.

In 1945, with a fellowship from the Indian government, he left for England to pursue a PhD at the University of Liverpool. Three years later, he continued on to Switzerland for a postdoctoral year at ETH Zurich, a university known for its contributions to chemistry, physics, and mathematics. Throughout his academic journey, Khorana encountered many mentors and advisors whom he credited with shaping his fascination with proteins and nucleic acids.

Khorana’s time in the US

In 1960, he move to the US for a role at the Institute for Enzyme Research in the University of Wisconsin. It was there that he made his Nobel-worthy discovery and became a naturalized American citizen. In 1970, Khorana joined the faculty at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology as the Alfred P. Sloan professor of biology and chemistry, the position he held until he died on Nov. 9, 2011 at age 89.

“As good as he was, he was one of the most modest people I have known,” MIT professor of molecular biology Uttam Rajbhandary said to MIT News after Khorana’s death. “What he accomplished in his life, coming from where he did, is truly incredible.”