If men and women participated equally in the global workplace, we could generate an additional $12 trillion in global economic growth in under a decade. Yet most of the world continues to allow economic discrimination against women, either through law or culture. Considered risk-averse, and yet untrustworthy, women’s ability to access credit is blocked in different ways around the world.

About 130 countries lack solid legal protection against gender discrimination in access to credit, according to the World Bank’s Women Business and the Law database. This includes famously progressive countries like Norway, Switzerland, and even Iceland.

Some countries, for instance, require or allow banks to demand a male signatory when opening an account, or to offer different interest rates depending on gender, or marital status (for women). Other countries may not actively discriminate against women in need of credit, but offer no specific laws making gender-based discrimination illegal, either.

Compounding this, says Mara Bolis, a senior advisor at Oxfam America, is structural bias, which is particularly strong in developing countries. “The way the credit system is set up is for most loans, the eligibility is asset-based; when the asset is land or property, [of which] women own a small percentage,” she told Quartz, noting that in many instances women aren’t allowed to inherit property, and even when they co-own it, they need the other owner’s approval before using it to get credit.

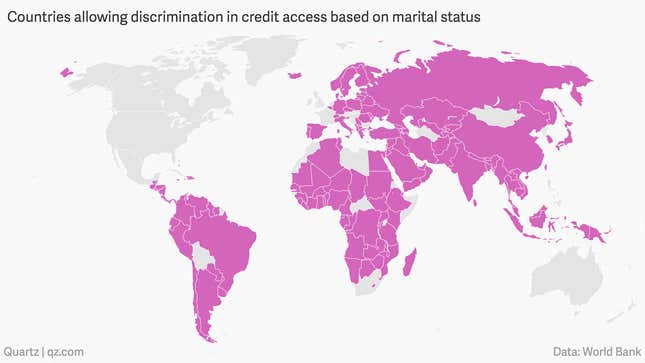

Meanwhile, some countries forbid banks from discriminating based on gender, but do allow discrimination based on marital status, from requiring a spouse to sign off a loan request to giving married women more favorable borrowing conditions.

Countries with no laws against direct gender-based discrimination, together with those that don’t limit discrimination caused by marital status, add up to three-quarters of the world’s countries.

“The way the system has been set up means that so many women are disqualified when they walk into the loan office,” says Bolis, who suggests other ways to gauge credit-worthiness, for instance consistency in paying bills, something that women can prove more easily, or using psychometric tests to measure propensity to pay or to default.

Trapped in a contradiction

Even when legal and cultural barriers to credit aren’t explicit, women are discriminated against in subtler way (with the exception of access to credit cards), and suffer from contradictory stereotypes about their financial skills. This explains why in a country like the US, where the law protects against direct and indirect gender discrimination, women still receive only 2.7% of all venture capital funds. Women of color receive an abysmal 0.2%.

Bolis says that in countries where women actively participate in business, it is often believed that women are risk-averse. For lenders, risk-averse means a potentially lower return on investment because a conservative borrower might not take on high-risk, high-reward opportunities. But while studies confirm that women tend to be less prone to risk-taking, Bolis suggests thinking of it as “risk aware,” rather than “risk averse”—investing in women could just as well be a more reliable long-term investment then men because they are much less likely to lose the initial capital.

Competing with this stereotype is another, contrary one: the idea that shopping is a feminine trait and are therefore more likely than men to spend frivolously. Bolis attributes this misconception to a fundamental “suspicion of women as economic actors.” Nevertheless, the belief that women lack financial skills can end up reducing their access to lines of credit—despite their apparent low proclivity for risk.

“It’s the worst of both worlds,” Bolis says, noting that lack of access to credit leads to fewer female-led companies, which in turn causes a lack of perspective on a much bigger business scale.