There’s only one active-duty vessel of the US Navy being held captive by a foreign government. It’s a North Korean tourist attraction.

On Jan. 23, 1968, North Korea attacked and seized the USS Pueblo, a barely armed spy ship that had been operating in international waters off its coast. Sent to gather intelligence on the secretive nation’s military, the vessel was unimpressive but did feature sensitive encryption equipment and intelligence documents. One American crewmember was killed in the seizure, and the 82 others were imprisoned and mistreated for nearly a year.

The 50th anniversary of ship’s capture serves as a reminder that relations between Washington and Pyongyang were tense long before Donald Trump and Kim Jong-un traded insults like ”little rocket man” and “dotard.” It also offers lessons for today.

While the two countries have been at odds for over half a century, some periods have been worse than others. The year 1968, even by today’s standards, was particularly bad. Then as now, the two sides exchanged strongly worded demands. Right after the ship’s capture, the US Navy insisted the crew be returned and that North Korea apologize, adding the US could demand compensation under international law.

Pyongyang wasn’t exactly cowed. The past few years had been marked by heightened tension and small skirmishes between the US and North Korea. Days earlier North Korean special forces had nearly succeeded in assassinating South Korea’s president at the Blue House, the equivalent of the White House in the US.

Major general Pak Chung-kuk said the USS Pueblo had been operating in North Korean waters, not international ones. Pyongyang demanded the US admit this, apologize, and promise that such intrusions would never happen again—in a signed document. Washington scoffed at the idea, but in December 1968 it finally went along, capping a year of deep diplomatic embarrassment.

In the intervening months, the US, embroiled in the Vietnam war, built up a large military presence around South Korea, deploying several aircraft carriers. The Soviet Union, a key North Korean ally, sent warships into the Sea of Japan. The stage was set for a serious conflict.

Meanwhile the imprisoned crew were not treated well, being starved, interrogated, beaten, and psychologically tortured by their captors. Commander Lloyd M. Bucher was put through a mock firing squad, and finally “confessed” to his crew’s transgressions when the captors threatened to kill his men in front of him.

For the North Koreans, the captured ship was a treasure trove of spy goodies, including intelligence machines and operating manuals. The US crew managed to destroy some of it, but experts believe much of value fell to North Korea and, through it, KGB officers in the Soviet Union.

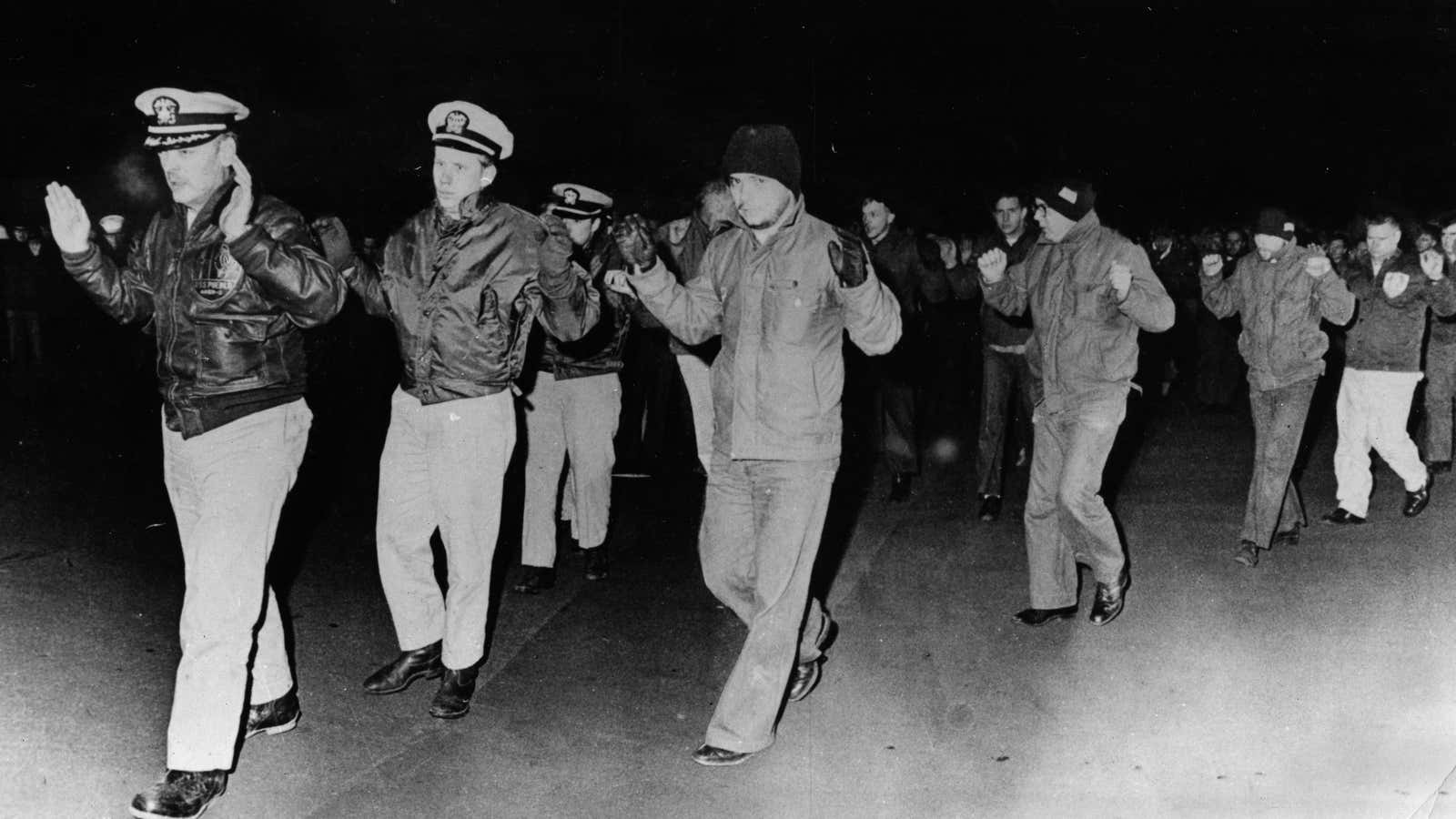

Once the men were released—in time for Christmas, in a welcome bit of positive news—the US retracted the admissions, apologies, and assurances it made to Pyongyang. But the damage was done: North Korea had humiliated the US and achieved a propaganda victory. Today the Cold War prize sits on the Potong River as part of a war museum in Pyongyang.

Throughout 1968, US president Lyndon Johnson faced heated calls for America to retaliate against North Korea. Various plans were put before him, including one involving nuclear strikes (pdf, p. 2). But Johnson showed restraint, opting instead for diplomatic efforts and secret talks with Pyongyang. Jack Cheevers, who wrote a book on the Pueblo incident, recently wondered if the Trump administration would show such restraint if faced with a similar provocation.

The Pueblo incident is a reminder that the Kim family regime—now in its third generation of authoritarian rule—is an unpredictable entity that doesn’t follow international norms. During the Cold War the US and Soviet Union had a gentleman’s agreement regarding spy ships: don’t interfere with ours and we won’t do so with yours. The US wrongly assumed that Pyongyang would play by the same rules. It did not.

Such assumptions could also prove dangerous today.