South Korean officials say they won’t ban cryptocurrency trading, but they have been cracking down hard on the country’s freewheeling market. Among the biggest victims are shadowy groups that profited handsomely from the unique opportunity to arbitrage cryptocurrency in Korea. Regulators recently said that they identified $600 million worth of “illegal foreign exchange trading using cryptocurrency,” but offered no details about what they were doing about it.

In Korea, a combination of restrictive licensing rules, limits on international transfers, and consumer enthusiasm for cryptocurrencies periodically produces what has become known as the “kimchi premium.” At times, bitcoin has traded for nearly 60% more in Korea than on global benchmark exchanges. That presents an enticing opportunity for people to acquire bitcoins abroad to sell at a hefty markup in Korea.

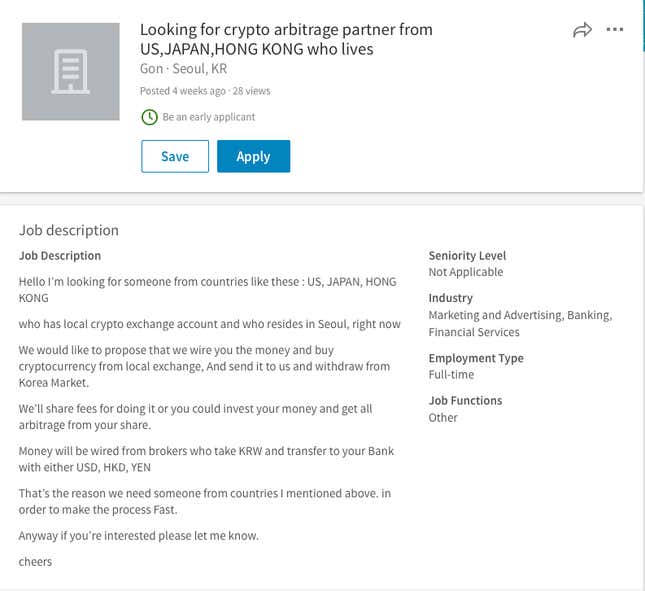

I heard first-hand about how these schemes work when I spotted an ad posted on LinkedIn seeking a “partner” to participate in a cryptocurrency arbitrage trade. The ad appeared to have been placed by a bot or other automated method, scraped from another ad in the online paper the Korea Observer (the person who placed the ad later told me the LinkedIn post was genuine). Tracing the ad back to its source, I found an e-mail address linked to a Skype account listed under the contact details.

I sent a Skype message introducing myself as a Quartz reporter, and I got an immediate reply from the poster, who refused to be named. When I asked the arbitrageur for details of his scheme, he was defensive. “I’m not allowed to talk about it,” he said. When I pressed, he replied: “In case you didn’t understand, that was me politely saying no.”

But I persisted, and eventually he began to tell me about two ways to getting around Korea’s restrictions on foreign exchange. ”Hopefully Koreans don’t read your paper,” he said, as he began to describe his methods.

English teachers and gangsters

He said the scheme involves moving money out of Korea via a patchwork of odd bedfellows that include both organized crime syndicates and former English teachers. The trader says he generated over $300,000 in profits this way in under eight weeks. Quartz was unable to independently verify the claims, but if true, the process likely skirts Korea’s foreign-exchange restrictions, which requires documentation and approval to transfer $50,000 worth of won outside the country in a year.

Given the authorities’ increasingly strict crackdown on crypto trading, gaining approval to move large sums of money in and out of the country for speculative arbitrage purposes is a risky proposition. This reduces liquidity and isolates Korean exchanges from global crypto markets, resulting in the price divergences. Bitcoin prices on Chinese exchanges—before they were shut down—also traded at a premium to global averages, thanks to currency controls.

Last November, a Seoul police officer was indicted (link in Korean) for running a bitcoin arbitrage scheme that used partners in China to buy bitcoins. He ran the scheme for 10 months, moving over $11 million out of the country. He awaits sentencing.

Such schemes “happen frequently,” says Erica Kang, chief operating officer of a blockchain research and consulting firm called Finector in Seoul, who recounted an incident in which a friend of hers was approached by an arbitrageur from China. Did the friend get involved? “Not sure,” she says.

Profiting from the “kimchi premium”

According to the trader, this is how the scheme works. Remember, the goal is to buy bitcoins cheaply outside Korea, and sell them on the country’s exchanges for a profit. This can only be done profitably when the spread between the bitcoin price in Korea and outside the country—the so-called kimchi premium—is more than 10 percentage points. The spread accounts for the risk and fees involved in getting the money out of Korea in the first place.

On the day I spoke to the trader, news of a government clampdown on crypto trading in Korea was fresh. The trader was unperturbed. “We can keep doing trades if kimchi premiums are above 10% or something,” he told me in a Skype message.

The trader said he has two partners in the scheme: one who keeps an eye on impending government crackdowns on foreign exchange, and another who acts as the go-between with “brokers” who can move money abroad. The trader described his partners as “literal gangsters” who he has known for years. ”I’m the one who can speak English and know the details for the whole bitcoin thing,” he said in a written Skype message.

The trader hands over cash to the broker, who is responsible for getting it to the ex-English teachers abroad. When asked how these brokers are able to evade Korea’s currency controls, the trader reiterated that they were part of organized crime groups. “Most of them are gangsters and it’s getting harder and harder to find them if you don’t know these people personally,” he said. The brokers skim 4% of the transferred funds as a fee. “For normal people I would say it’s almost impossible to find [a broker] these days,” he said.

One crucial feature of this operation is that no money actually leaves Korean shores. Instead, the gangsters—er, brokers—reconcile credits and debits internally. If the trader deposits won with a broker in Seoul, the broker doesn’t wire the money to a counterparty overseas. Instead, the overseas partner credits the equivalent from his own supply of funds.

This is a trust-based operation that’s similar to the hawala money-transfer system originating from Silk Road traders in the 8th century, and still used in informal economies today. (It’s known as hwan-chi-gi in Korea.) And since these are gangsters we’re talking about, fear is as important as trust in keeping everyone honest with their virtual debits and credits.

“Basically they have people in [the destination] country with a lot of cash,” the trader said. “So they can send the cash to you directly without using banks.” In this case, the trader’s overseas partners are in Hong Kong and the United States.

Once the money is credited outside Korea, it is transferred to the ex-English teachers to deposit at a cryptocurrency exchange and purchase the coins they are instructed to. The buyers are paid 5% of the funds they are given. “They were just ordinary English teachers in Korea,” the trader said. “Now they don’t have a job, who can resist sweet and free money with zero effort?”

Once the English teachers-turned-clandestine-arbitrageurs buy the coins, they send them to the trader in Korea. (Stateless, decentralized cryptocurrencies are much more easily transferred across borders, essentially by swapping wallet passwords.) The trader then sells the coins for a profit on Korean exchanges. He isn’t picky about which cryptoassets he arbitrages in this way. “Whatever coins have the largest kimchi premium,” he said, but mostly bitcoin, ethereum, and ripple.

The market maker

The trader said he’s a 28-year-old in Seoul who used to run an import-export business selling novelty tech products. His business before the crypto gambit was to import products from Alibaba and Kickstarter, and resell them on Korean e-commerce platforms—another form of arbitrage.

About two months ago, the trader saw a job posting on the gig-work platform Upwork. Some Dutch crypto traders were seeking a partner who could sell coins in Korea to execute the “kimchi premium” trade. The trader said he worked with the Dutch partners for a while, learning how to execute the trade, then went into business for himself.

“What the Dutch guys wanted was pretty boring,” he said. The scheme relied on regulated bank transfers instead of more shadowy money-transfer methods. “They didn’t have brokers, the transactions were slow, and there were limits,” he said.

A search on the Korea Observer site turns up an ad seeking a partner in the country to perform crypto arbitrage. A check on Upwork also reveals multiple ads seeking such partnerships.

The Korean crypto-trading scene is rife with rumors about illegal arbitrage operations, which rise and fall with bitcoin prices. (In general, the higher the global bitcoin price, the higher the kimchi premium.) Andrew Kim works at the accounting and consulting firm EY, but is better known in the cryptocurrency markets by his Twitter handle, Crypto Korean. He describes a variety of schemes used to evade the country’s capital controls and profit from crypto arbitrage.

The schemes run the gamut from people paid by crime syndicates to squirrel bags of cash overseas for “tourism” purposes, to vast money-laundering schemes involving Chinese travelers and money-changers in Seoul’s downtown shopping districts.

Some of the Chinese tourists thronging Seoul’s glittering malls work for Chinese bitcoin miners: They sell bitcoins on Korean exchanges, exchange the won for yuan at the dozens of small stalls offering money-exchange services commonly found on the streets around the malls, and then bring that back to the mainland. Chinese miners are in a bind because crypto trading has been banned there, but they have to convert their crypto holdings to yuan to pay the bills. “Apparently those sums were massive,” Kim says.

I ask the trader whether he’s afraid of getting caught breaking the rules, which could trigger uncomfortable tax investigations, money-laundering accusations, or worse. “For now, it’s okay to buy bitcoin as long as you don’t get caught with the brokers,” he said. “As long as we don’t get caught in action, there are no risks.”

Not long after we spoke, a sharp decline in cryptocurrency prices and greater regulatory scrutiny all but erased the kimchi premium. Contacted again, the trader said his arbitrage activity had slowed down as a result. He wasn’t optimistic about the premium returning, but things can change fast in the crypto markets—the recent spike in the premium followed months of calm—and where there is a will there is always a way.

Hailey Jo contributed reporting.