Is gross domestic product a sufficient measure of an economy’s health? Many argue that GDP, which counts the sum of the goods and services produced by a nation, fails to reflect a population’s wellbeing, because it accounts for neither distribution of income nor extractive effects such as pollution.

This week, the World Bank published an ambitious project to measure economies by wealth, to get a more complete picture of a nation’s health, both in the present and the future. The Changing Wealth of Nations analyzes the wealth of 141 countries, from 1995 to 2014. The report argues that wealth is a better judge of economic success because it measures the flow of income that a country’s assets generate over time—although it is significantly more challenging to measure. “A country’s level of economic development is strongly related to the composition of its national wealth,” the report states.

Wealth includes all assets, which means human capital (the value of earnings over a person’s lifetime), natural capital (energy, minerals, agricultural land), produced capital (machinery, buildings, urban land), and net foreign assets.

Assessing an economy by GDP instead of wealth is like looking exclusively at a company’s income statements without considering the assets on its balance sheet. A company can make its income look good for a short time by liquidating assets, but over the long run this will reduce the firm’s productive capacity and other means of generating income in the future.

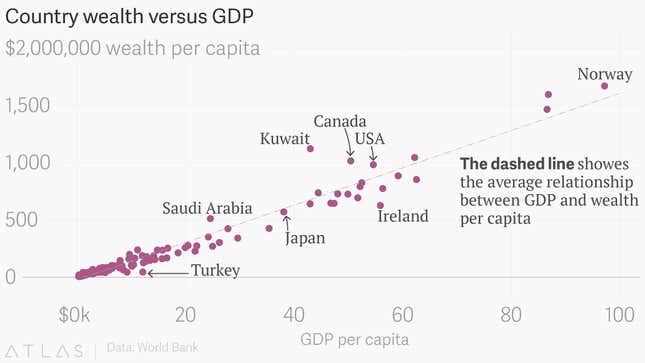

The same applies to a country. GDP “does not reflect depreciation and depletion of assets, whether investment and accumulation of wealth are keeping pace with population growth, or whether the mix of assets is consistent with a country’s development goals,” the report states. That said, for most countries GDP is strongly correlated to wealth.

However, there are outliers. For example, in Turkey, GDP outpaces wealth. Kuwait has much more wealth per capita than its GDP (as does Saudi Arabia, but to a lesser extent). Kuwait and Saudi Arabia have the resources to make investments far into future. Saudi Arabia is making these efforts, diversifying its economy away from oil under a plan known as Vision 2030.

The push for wealth accounting also came up in the 1980s, the World Bank says. Back then, there were concerns that the rapid growth in GDP of resource-rich countries was mostly the result of liquidating natural capital—wealth accounts would have been a better measurement of an economy’s health at the time.

In many rich countries, human capital tends to be the largest component of wealth, whereas natural capital is higher in low- and middle-income economies. Global wealth increased 66%, to $1,143 trillion, between 1995 to 2014. And while total wealth increased almost everywhere, per capita wealth did not. Some low-income economies experienced a decline because population growth outpaced investment, especially in parts of Africa. The share of global wealth held by low-income countries remained at about 1% throughout the period of study, even as their share of the world population increased from 6% to 8%.

The table below shows the share of wealth that comes from different types of capital for the 10 most populous countries in the world. Human capital accounts for roughly two-thirds of global wealth.

As global economies develop, the composition of wealth changes. In low- and middle-income countries, human capital wealth on a per-capita basis tends to increase, while aging populations and stagnant wage growth means that this component shrinks for richer countries. Still, in high-income countries human capital comprises some 70% of wealth, and natural capital only 3%.

Simply having natural capital is not enough to ensure the economic development of lower-income countries, the World Bank says. Of the 24 countries classified low-income since 1995, 12 are resource rich, the organization says.

Globally, another way to increase wealth is through gender equality. The World Bank finds that women account for less than 40% of human capital wealth because of their lower earnings, lower labor force participation, and fewer average hours of work. If the gender pay gap were closed, the world would experience a 18% increase in human capital wealth.