Just off the European E18 highway some 210km south of Oslo lies an industrial park called Brokelandsheia. It is an unassuming cluster of a few hundred workers, a small collection of warehouses, a Statoil gas station and a 24-hour cafe and hotel called Cinderella. Next week, the Cinderella cafe is going to see a surge in business: It is the location of one of six supercharger stations Tesla has built in Norway. They will all be operational by this weekend. Tesla’s plan is to cover Europe with superchargers—fast, free charging stations for Tesla’s electric vehicles (EVs)—roughly 200 km apart, and Norway is the first country outside the US to get them.

With its tiny population of under five million, remote location at one corner of Europe, and vast empty tracts of land stretching in a thin strip all the way past the Arctic Circle, Norway does not seem like the ideal place to start building a continent-sized network of chargers. For Tesla, the American electric-car company headed by Elon Musk, Holland may seem more sensible. It is is barely 400 km from top to bottom, its terrain is almost entirely flat and it represents the highest sales of Tesla’s Model S outside the United States. It also the location of Tesla’s European headquarters. But Norway has the highest per-capita sales of Tesla, and indeed electric cars, anywhere in the world.

On August 7, Norway received the first Tesla Model S delivered in Europe. Tesla does not release sales by country but the company’s Scandinavia spokesman, Esben Pedersen, indicated that Norway would receive over 1,000 deliveries by the end of 2013. (Analysts’ estimates are more conservative, forecasting closer to 800 deliveries.) That sounds minuscule compared to sales in America—California registered 1,097 Tesla cars in June alone. But the 4,474 electric vehicles (most of them cars) that were added to Norwegian roads in 2012 accounted for 3% of all cars sold in Norway. Nowhere else even comes close. In the US, 0.1% of cars sold in 2012 were electric.

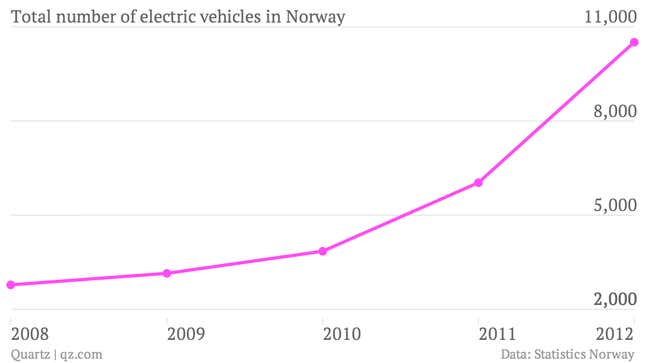

2,500 new electric vehicles have been registered so far this year, according to Statistics Norway. Those numbers have picked up in recent years as makers of electric cars spot Norway’s potential. ”Until only three or four years ago, very few models were available. Sales of EVs have been very supply driven,” says Bjørn Gjestvang, who looks at the automotive sector at KPMG, a big consulting firm.

Giving it away

Tesla’s focus on Norway comes from the same root as Norway’s fascination with electric vehicles: an incentive system so generous that it seems almost financially unsound to not buy one. Cars are subject to a raft of taxes, including value added tax and purchase tax, which on average add 50% to the cost of a vehicle. Electric vehicles are exempt from these taxes. As a result, a Tesla Model S that is priced at $62,500 in the United States, costs only a little more—roughly $73,000—in Norway. Without the exemptions, it would cost more than $100,000.

Moreover, electric vehicles get free parking, free charging, and can use the bus lanes. They are also exempt from road tolls and tunnel-use charges. As Norway builds more and better roads, a 250 km-route that once cost a driver on it $10 in tolls now costs as much as five times as much. The savings are enormous for those with electric cars. Bjart Holtsmark of Statistics Norway estimates in a paper under review by Environmental Science and Policy that an electric car-owner living in a suburb of Oslo would save over $8,100 a year as compared to her petrol-head counterparts. No estimate exists for how much this costs Norway as a whole.

The oil state with a carbon-neutral heart

Despite having grown rich through the production and export of oil and gas, Norway uses very little of the stuff itself. Nor does it just give fuel away to its citizens, unlike many oil-producing countries. Petrol costs more than $2 to the litre, over twice the US rate and about 20 times what it costs in Saudi Arabia. All but 1% of the power produced in Norway comes from hydroelectricity, making it among the cleanest producers of energy in the world. The idea then is that electric vehicles can, with the exception of production costs, be entirely free of emissions.

That is one reason for the generous incentive structure. Statistics Norway’s Holtsmark posits that Norway’s desire to have an indigenous automobile industry may also be a part of the legacy. The government set up a plant to domestically produce an electric vehicle, called Think City, in 1991. Despite the subsidies, Think City never really took off. It was declared bankrupt in 2011 and production has since ceased.

Missing the goal

Norway’s incentive policy is not without its critics. They point out that the cars don’t really have zero emissions because Norway is linked to the European electric grid, which means that any extra hydroelectric power not exported by Norway is power that Europe will generate through dirtier methods.

Others argue that by linking the bulk of subsidies to a kind of technology rather than emissions themselves, Norway doesn’t incentivize its citizens to buy more advanced cars with lower emissions. Indeed, the hefty cost of a new car might perversely encourage Norwegians to continue driving older, dirtier cars to get more value out of them. Only the purchase tax is linked to emissions; all the others are expressly for electric vehicles. (Denmark subsidizes electric cars but offers nothing to hybrids such as the Toyota Prius. The UK follows an emissions-based policy that in practice frees electric vehicles from road tax and congestion charges.)

Second cars and bus lanes

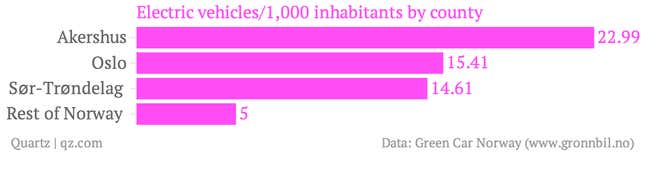

But perhaps the biggest criticism of Norway’s incentive policy is that it has encouraged rich suburban dwellers to buy second and third cars and to give up public transport in order to commute to work. The reason for this is quite straightforward: most electric cars now sold in Norway have a range of about 100 km. The Nissan Leaf, the best selling electric car in Norway, claims a range of 120 km. That is not much in a country where the the two largest cities are nearly 500 km apart. Replacing a gas-guzzling family car with an small electric vehicle would be silly. Still, the numbers are remarkable: Residents of the municipality of Akershus, neighboring Oslo, bought 23 electric vehicles for every 1,000 people in 2012. Asker, a village in that county, had more than 12 EVs per 1,000 inhabitants the previous year. Unsurprisingly, it is an affluent commuter village about 25 km away from Oslo.

Separately, a 2009 study (link in Norwegian) found that those with electric vehicles took public transport, walked or cycled only a fraction as much as the general population. Moreover, they drove nearly twice as much as the general population. The same study found that electric-car owners drove more and took public transport less than they did before acquiring the vehicle. Residents of big Norwegian cities are beginning to notice that their bus lanes are often full of cars. Though all sides of the political spectrum have agreed to keep Norway’s incentives in place until the end of 2017, the privilege to drive in bus lanes may be one early casualty.

Tesla moves in…

Tesla is uniquely placed to take advantage of Norway’s market. It appeals to Norwegian drivers for several reasons. The Model S’s stylish design and superb safety ratings are among them. More important is its range, advertised at about 400 km. “If you look what could be used as your number one vehicle, then it’s only Tesla which is in that area,” says John Thomas Sørhaug, who heads KPMG’s automotive sector in Norway. That is an attractive proposition for many Norwegians, and also one that has the potential to silence critics of Norway’s incentive regime for electric vehicles.

Tesla’s $73,000-price tag makes it far more expensive than other electric cars. Yet its size, speed, style and features put it in the same league as luxury BMWs and Audis—but at less than half the price. It is no surprise Norwegians are enthusiastic.

None of this has escaped Tesla’s notice. Last year, it employed five or six people in Norway. Today it has 30 and is still hiring. It has showrooms in airports and shopping malls. Service outlets are being established in Oslo, Bergen and Trondheim, some of Norway’s biggest cities. In other parts of the country, Tesla service trucks will travel to the location of the car and fix it on the spot if the problem is not major.

…And so do others

Tesla is not the only one that has noticed Norway’s advantages. Sørhaug says 2014 will see many big manufacturers bringing new electric cars to Norway, “fully aligning” supply with demand. Electric cars in Norway are on track to make up 4% of all sales this year, up a third from 2012. The country is more ambitious yet. It is aiming to cut CO2 emissions to 85 grams/km by 2020, 10gm/km lower than the EU target. To achieve that, electric vehicles need to make up 7.5% of the sales by 2015 and 10% by 2020, says Gjestvang.

If that does happen, some incentives (chief among them bus lanes) are likely to vanish. That could change the equation for buyers, and indeed for manufacturers such as Tesla. But it will be fascinating to watch.