It’s amazing when you stand back and think about it. The fastest-growing industry in the world’s most powerful economy can scarcely pay its workers enough to live.

No wonder thousands of fast-food workers have gone on strike to protest their measly wages and non-existent benefits, demanding a $15-per-hour minimum wage, which would more than double some of their hourly income. These aren’t teenagers, after all. A quarter of fast-food workers are raising a child. Forty percent are older than 25.

But sympathy and optimism are two separate things. And when it comes to the fast-food worker strikes and dramatically raising wages for food service employees, I’m only feeling the former.

Let’s begin by acknowledging that it’s still early, you can’t rush to measure the success of a national protest movement, and workers have already achieved some small, store-specific victories, “from scheduling changes, to raises, to the restoration of a tip jar.”

But let’s also be realistic. The strikes would have a much better shot at inspiring a change in franchise- and corporate-level policy if fast-food chains perceived one of two threats: (a) a threat to the steady supply of food-service workers who want to be employed at any wage and (b) a threat from consumers demanding higher wages for their fast-food clerks by not buying burgers and fries at McDonald’s.

Instead, the big-picture doesn’t reveal either of these pressure points. Fast-food jobs aren’t merely scattered among the most despondent corners of the economy. They’re growing fastest among some of the richest and most-educated metros. Bridgeport, Conn., Salt Lake City, Raleigh, Chapel Hill, and Washington, D.C., are among the five areas with the most growth in food service work between 2010 and 2013.

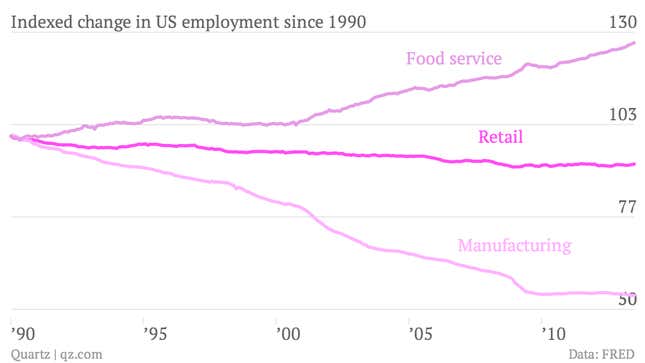

Study this graph. It shows the post-1990 change in three big industries’ share of total employment. All three historically attract young, low-educated workers—the bread and butter of fast-food employment. Manufacturing’s share of all jobs fell by nearly 50%. Retail, which absorbed a lot of the slack from manufacturing’s slowdown in the 1970s and 1980s, has flat-lined. Food services? Shot up by 25%.

This graph doesn’t tell us everything you need to know about why low wages in food services are probably here to stay. But it does suggest that the collapse of middle-income stalwarts like manufacturing has left a glut of young low-skill workers who are rushing into to fill local service-sector needs at big-box stores and fast-food chains. And that, to me, suggests another thing: That there are more people willing to do these jobs than there are people willing to strike.

This isn’t to say that intervention is impossible. Congress could decide in September to double the minimum wage or triple the Earned Income Tax Credit. But it won’t. And without some sort of third-party intervention, it is hard for me to see how the higher-wage movement succeeds on the streets.

Derek Thompson is a senior editor at The Atlantic, where he oversees business coverage for the website.

This originally appeared on The Atlantic. Also on our sister site:

The magical world where McDonald’s pays $15 an hour? It’s Australia.