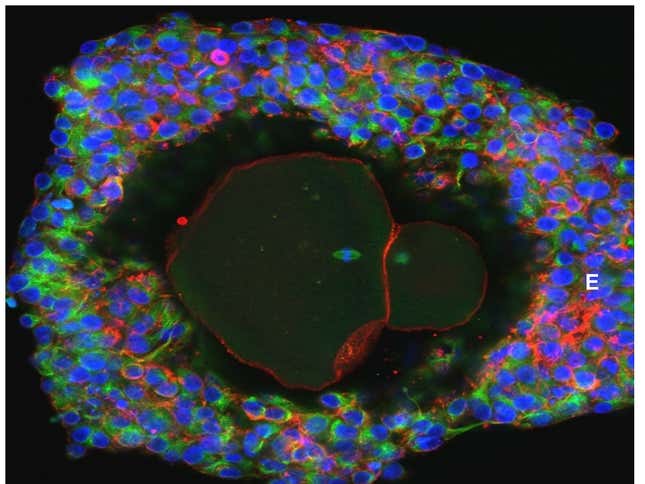

Ovaries are the best incubators known to womankind—chemically nurturing and pruning human eggs until they’re fully mature and ready to be fertilized. Scientists have never quite been able to recreate the process.

But after 30 years of work, researchers at the University of Edinburgh in the UK have found a way to grow fully mature eggs outside the human body. In a lab setting, they coaxed immature eggs to grow to the point where they’d be ready to be fertilized.

“Apart from any clinical applications, this is a big breakthrough in improving understanding of human egg development,” Evelyn Telfer, a developmental biologist and coauthor of the paper, told the BBC.

For this study, which was published on Feb. 8 in the journal Molecular Human Reproduction, researchers had to create those exact growth circumstances in a lab setting. They used 48 immature eggs donated by 10 women in their 20s and 30s. Over the course of 22 days, they carefully brought these eggs to develop to the point where they could be fertilized, although they weren’t for this particular study. Normally, the maturation process inside the body takes about two weeks.

Researchers are hopeful that this discovery is a first step toward helping girls diagnosed with childhood cancer keep their fertility in adulthood. Certain types of radiation and chemotherapy destroy the finite number of eggs that girls are born with. Because these children haven’t gone through puberty, there’s no way to extract and freeze the eggs, which is often what adult women who need cancer treatment do. And although it’s possible to save and freeze young girls’ ovarian tissue for later use, sometimes the freezing process damages this tissue, still rendering the woman infertile.

The University of Edinburgh team’s methods are far from perfect. Only nine of the 48 eggs successfully made it through the entire trial. Plus, not all of them were the super-young eggs that had to be brought entirely through development; some had the advantage of being slightly more mature, meaning that scientists had to only partially grow them. But the fact that it could be done at all is a huge step forward in developmental biology: Previous teams had been able to coax eggs to various stages of maturity in the lab, but none to completion.

Telfer and her team recognize that they need to refine the process to ensure that these lab-grown eggs are just as healthy as those inside a woman’s body. “The next step would be to try and fertilize these eggs and then to test the embryos that were produced, and then to go back and improve each of the steps,” she told the Guardian.