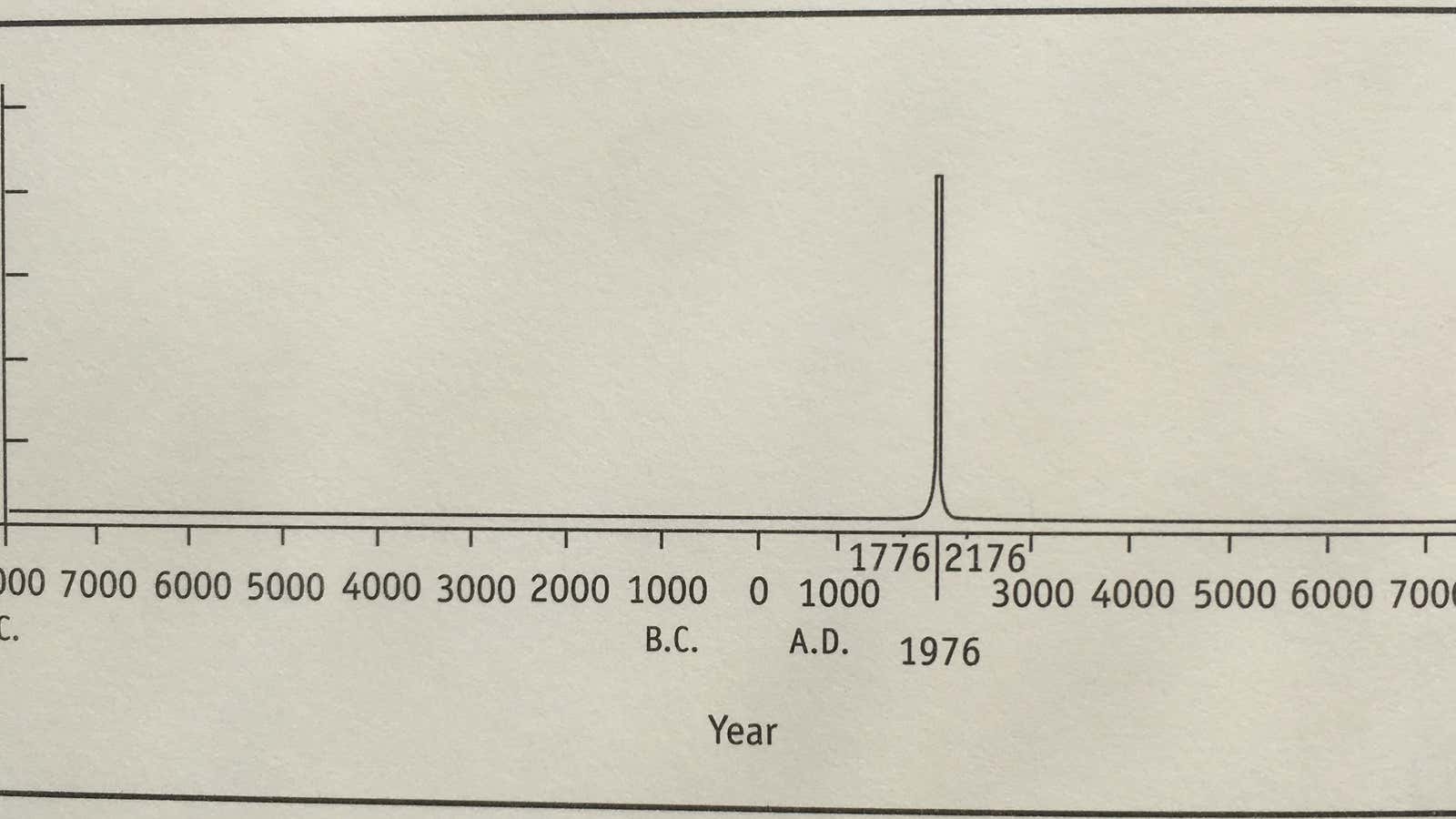

We like to think of the story of human growth as a single, long ascent. In fact, it’s a solitary spike. The population growth rate hovered just above zero for more than 10,000 years. Only after something happened in the 1700s did the growth rate begin to climb, and climb, and climb.

With the Industrial Revolution gathering steam, the global population growth rate jumped from around 0.02% per year in the early 1400s to 0.23% in 1600 and then 0.33% in the mid-1700s. By 1970, it peaked at about 2% per year, and began its return to the norm. Last year, population growth tumbled past 1.1% per year on its downward trajectory that demographers expect will approach zero (or even fall below it) by the end of the century.

What’s happening? “Each burst of technological innovation leads to a burst of population,” says Ron Lee, an emeritus professor of demography and economics at University of California, Berkeley. Each time, society has been transformed by new inventions (planting, stone tools, metallurgy, steam power), it set off a roughly ten-fold increase in the human population, and then a demographic transition to very low growth for thousands of years. This phenomenon has occurred twice before, says Lee: when humans coalesced into hunter-gatherer societies at least 2 million years ago, and after the advent of agriculture in the Middle East about 12,000 years ago.

The latest population explosion comes courtesy of better nutrition, higher birth rates, and lower mortality. It was a long slog to get there, wrote the late economist W.W. Rostrow in his 1998 book The Great Population Spike and After. Centuries were required to build nation-states and then the class of merchants and global trade networks to power the European economy. Once those were in place, the Industrial Revolution took hold and countries began to follow almost identical population trajectories around the world. UK led in the 1700s, followed by parts of Europe, the US and finally countries in Asia. Today, only Africa (with some exceptions) is still entering the “take-off” stage of rapid population growth and development.

Yet the rising education and wealth that accompanied modern civilization tamped down birthrates as well. In the developed world, fertility rates are below 1.72 births per woman, well under the replacement level of 2.1 births. More than a dozen countries, including Japan and Spain, are now in steady decline. Globally, the human birthrate will dip below replacement level by 2070, according to the latest figures from the UN Population Division.

Demography, Rostrow asserted, is perhaps the most potent force reshaping our world, and we’re now in uncharted territory. Industrialized countries have no experience managing the transition to societies in which the growth in the number of aged citizens rivals that of younger workers as populations decline for the foreseeable future. With Japan and a few other countries several years into that future, the strain is showing around the world. Populism, in part, flows from the demands placed on societies as birth rates slow or go into reverse: slowing economic growth, clashes over immigration, financial battles over pensions or taxes, and the need to expand the workforce. Perhaps the most difficult politically will be immigration.

The reinvention of the US from a majority “white” country (a dubious designation: most European immigrants to the US were seen as racially distinct at the time) to one that is truly a global mix of races and cultures is unprecedented. At current trends, the US will be the first such country to make the transition to a “majority-minority” nation by around 2050 as Hispanics, Asians, African-Americans and other racial groups form a plurality (although history suggests that racial standards will shift dramatically over time as minorities in the US inter-marry and identify with mainstream culture). “Managing a peaceful transition from a US which is dominated by white European culture to one which is truly multi-racial, and very different from Europe, will be the greatest single challenge the US will face in the coming generation,” wrote British financial reporter Hamish McRae in his 1996 book The World in 2020. That two decade-old prediction could have served as the central plank for Donald Trump’s successful campaign for the White House.

But Lee notes the trends lines are actually positive. “In many ways,” says Lee, “it’s a very optimistic picture.” Poverty is down. Educational opportunities are spreading. Average lifespans are longer. Humanity, in material terms, has never had it quite so good. Yet nothing is inevitable.

Nuclear war and environmental collapse may permanently derail humanity’s progress, says Lee. The probability of catastrophe is rising, not falling. Even in humanity’s most recent population spike, an outlier is visible. Between 1600 and 1650, the human population stopped growing. A combination of severe climate change, a particularly brutal spell of the Little Ice Age, and sustained warfare battered Europe, keeping populations static and people miserable.

There’s no guarantee such things won’t happen again.