For those comfortable with reading and writing in English, it can be hard to imagine what it’s like to experience a world of limited content. And yet, that’s just what millions of Indians face online every day.

Even as social media giants such as Facebook and WhatsApp, and browsers such as Alibaba’s UC, increasingly support a range of Indian languages, regional language content still accounts for well below 1% of the internet.

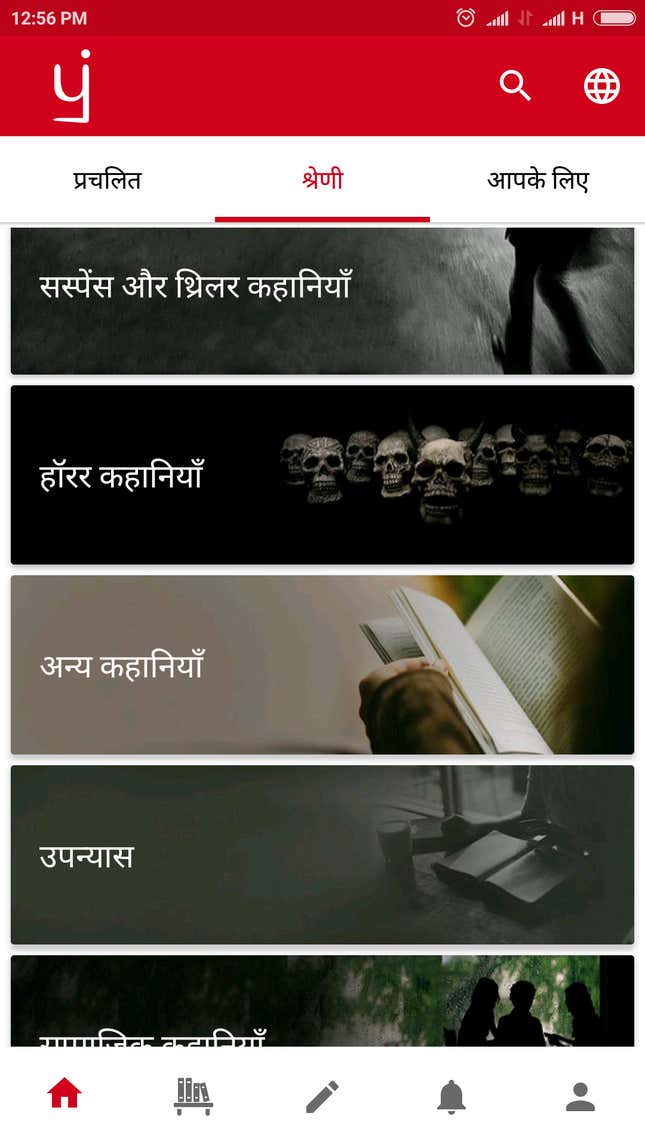

So, since 2015, a self-publishing startup has been opening the door to more longform content in these underrepresented languages. Bengaluru-based Pratilipi is building a bridge between writers and readers looking for fiction, non-fiction, poetry, and more in Hindi, Gujarati. Tamil, Telugu, Marathi, Malayalam, Kannada, and Bengali.

The company started out with a website and now has an app with over a million downloads on the Google Play Store and a 4.8 star rating. In February, it raised $4.3 million in a series A round of funding that was led by the Omdiyar Network, and its young founders made it to Forbes India’s 30 under 30 2018 list.

Long before all this, though, 29-year-old co-founder Ranjeet Pratap Singh was just another Indian trying desperately to find something to read.

The back story

Singh grew up in a small village in the northern Indian state of Uttar Pradesh where most people spoke Hindi and few managed a simple sentence in English. A voracious reader, he devoured Hindi comics before moving to literature. By the time he began studying engineering at the Kalinga Institute of Industrial Technology in Bhubaneswar, Odisha, in 2006, he realised he was running out of options.

“Offline bookstores can only carry at max maybe a couple of thousand titles. If you read as much as I did then generally you had read all the good ones. And online, there wasn’t really much,” Singh explained. “So I started reading English literature, but I also started cribbing to my friends that this is not how it should be.”

But he didn’t do anything about it then, going on to pursue an MBA in 2010 and subsequently working for Vodafone for several years. It wasn’t until he decided to quit his job to do something more challenging that the idea for Pratilipi began to take shape.

“I wanted to do something which would be hard, but also something that can impact a lot more people. This is roughly also when my friends started calling me back and saying, ‘you have been cribbing about this for like half a decade, so if nobody else has built something like this, why don’t you do it?'” he said.

In 2014, along with friends and former colleagues Prashant Gupta, Sahradayi Modi, Rahul Ranjan, and Sankaranarayanan Devarajan, Singh set out to build a platform where anyone could share stories written in Hindi and Gujarati, and anyone could read them.

Borrowing around Rs35 lakh ($53,865) from friends, the team started out with a simple website and called the company Pratilipi, Sanskrit for “copy.” Singh says the name was chosen to reflect the idea that you become what you read. The spirit of Pratilipi, he explained, echoes what George RR Martin wrote in A Dance with Dragons, from the Game of Thrones series: “A reader lives a thousand lives before he dies…The man who never reads lives only one.”

But before getting any readers, Pratilipi needed writers.

Getting ’em to write

In its early days, the team sourced public domain content in regional languages and met with hundreds of writers, seeking permission to publish their stories on Pratilipi.

“Most of these were people who had published books or worked for newspapers or magazines,” Singh said. “Then, about a year back or so is when the magic started happening. People who are not writers, who have never written anything before…they started writing.”

Today, across its website and app, which was launched over a year ago, Pratilipi has around 160,000 published pieces and a user-base of 1.3 million people who follow their favourite writers and leave reviews. In January this year, roughly 11,500 pieces were published, which Singh says is between three and four times the amount published the same time last year. Fiction dominates the platform, accounting for about 70% of the content, and some 60% of the writers are men, though 71% of the readers are women.

Tamil writing was introduced in January 2015, and Kannada and Telugu the following year. While Hindi remains the most popular language among both writers and readers, there are sizable communities producing and consuming content in the other seven languages. Together, these eight languages are spoken by over 80% of India’s population, many of whom, like Singh himself, have always wanted to read in their own tongue.

The next billion

India’s publishing industry is reportedly one of the fastest-growing in the world, though it’s dominated by educational books. A 2015 report by Nielsen said that 55% of trade sales were of English books, with Hindi and other languages accounting for 35% and 10%, respectively. However, there’s hardly any accurate data available on the number of books produced in different languages. Given the onerous process in India of getting International Standard Book Number (ISBN) codes, which are used as unique identifiers for books, many local publishers have to skip them, making it hard to track the exact number of titles published in the country every year.

Nevertheless, what is known is that regional language publishers have struggled with distribution, depending on their own retail outlets or book fairs to reach readers. But amid growing internet access and the availability of affordable smartphones, things are slowly changing, with ebooks in five regional languages now available on Amazon Kindle, for instance. Other self-publishing companies, such as Matrubharti, are also offering regional language content to tech-savvy users.

There’s still a lot of room to grow.

A 2017 report (pdf) by KPMG India and Google estimated that Indian language internet users will number a staggering 536 million by 2021, accounting for 75% of its total internet user base. Given that the internet remains overwhelmingly dominated by English content, apps like Pratilipi that cater to Indian languages have lots of headroom.

The Omidyar Network, the philanthropic venture capital firm founded by Pierre Omidyar, recognised this. Pratilipi is tackling all the issues related to the scarcity of content in Indian regional languages, according to Siddharth Nautiyal, investment partner at the Omidyar Network in India.

“They were coming up with what is by far the leading Indian-language long-form community…people were able to come up and trust the platform…in a format that was very specific to the (way Indians) would like to consume content,” Nautiyal said, explaining his firm’s move to invest in the company this February.

But challenges remain, notably in balancing the needs and interests of both writers and readers.

Challenges ahead

“This thing only scales when lots and lots of authors in multiple languages find it worth their while to contribute here…and over time I’m sure some of these authors will look for monetisation,” Nautiyal added. “On the other side, they have to keep making sure that readers stay engaged.”

Singh said Pratilipi is “not even close” to profitability, adding that it’s also not a short-term goal. But it has plans to get more users on board. These include the launch of audio content for those who can’t read complex sentences, or want to consume content on the move. Its language options are also set to expand this year.

And in the long term, the idea is to find a way to get Indians, over and above its 23,000 listed authors, to write.

“We believe that everybody has a story within themselves, and if we can give them the right tools and the right incentive, there’s no reason why we shouldn’t have 10 million story creators,” Singh said.