A huge new Stanford and Harvard study proves that US inequality isn’t just about class

For decades, an increasingly loud chorus has claimed that economic inequality is primarily driven by class, with other possible reasons for disparities, such as race, playing a lesser role. They say that it is counterproductive to focus on inequality between races—instead, it is better to consider the inequality between all of America’s poor and its increasingly rich elite. A new study (pdf) by economists at Stanford, Harvard, and the US Census Bureau seems to refute that idea.

For decades, an increasingly loud chorus has claimed that economic inequality is primarily driven by class, with other possible reasons for disparities, such as race, playing a lesser role. They say that it is counterproductive to focus on inequality between races—instead, it is better to consider the inequality between all of America’s poor and its increasingly rich elite. A new study (pdf) by economists at Stanford, Harvard, and the US Census Bureau seems to refute that idea.

The paper, which assesses data on intergenerational economic mobility for 20 million US children and their parents, shows that when it comes to racial inequality, primarily between black and white Americans, class can’t explain the gap.

The findings come from the Equality of Opportunity project, spearheaded by Stanford economist Raj Chetty, revealed particularly stark results about the prospects for black boys. Black American men, even from wealthy families, are much more likely to end up in lower income brackets than white men who grew up poorer.

The study focuses on children born in the US between 1978 and 1983, or authorized immigrants who came to the US in childhood, covering virtually all Americans now in their late 30s. It pulls apart many long-held hypotheses about racial inequality, such as the gap being explained by education, family background, neighborhoods, innate ability, and the like. One of the report’s key takeaways is this:

When we compare the outcomes of black and white men who grow up in two-parent families with similar levels of income, wealth, and education, we continue to find that the black men still have substantially lower incomes in adulthood.

Downward mobility

In the US, Hispanics have high rates of upward income mobility across generations, which puts them on path to closing the income inequality gap with white Americans, according to the research.

However black Americans (and American Indians) not only have lower rates of upward mobility, they also have higher rates of downward mobility. This implies that closing the wide and persistent income inequality gap over time is currently out of reach.

For example, black children born to parents in the bottom household income quintile (the poorest 20%) have just a 2.5% chance of rising to the top quintile (the richest 20%) of household income. For whites, the probability is 10.6%. Meanwhile, black children born to parents in the top income quintile are almost as likely to fall down to the bottom quintile as adults as they are to remain in the top quintile. White children born into the top quintile are nearly five times as likely to stay there as they are to fall to the bottom.

For black children in particular, class status is not permanent, and no guarantee of future prosperity.

The study finds that this black-white income gap is also entirely created by differences in outcomes for men, not women. Among those who grow up in families with comparable incomes, black women earn slightly more than white women. Black men, by contrast, earned “substantially” less than white men with similar parental incomes.

For men, this disparity is also seen in high-school completion rates, college attendance rates, and incarceration. The latter is seriously troubling: 21% of black men born into the lowest-income families are incarcerated on a given day, far higher than any other group.

99% of America

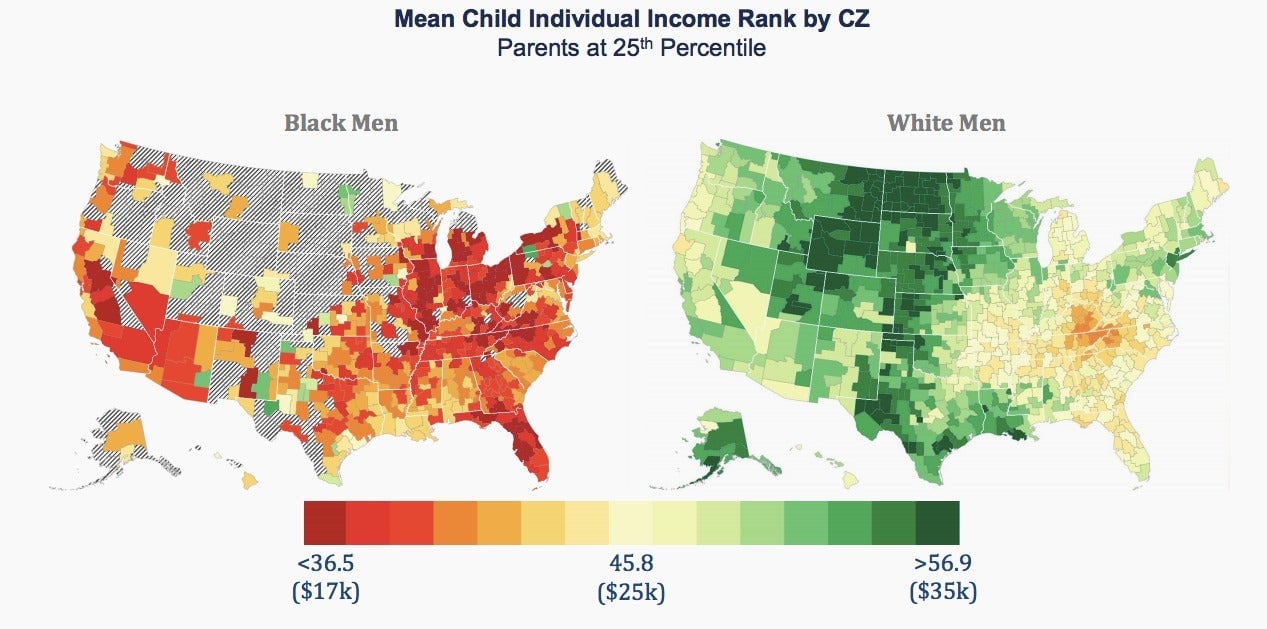

Geography doesn’t make much of a difference. “In 99% of neighborhoods in the United States, black boys earn less in adulthood than white boys who grow up in families with comparable income,” the report says. This was true right down to children who grew up on the same block. The authors say this reveals that intergenerational equality can’t be explained by neighborhood-level resources alone, such as the quality of schools.

The lack of economic mobility and the racial inequality gap paints a picture of two different Americas. In “good” neighorhoods with low poverty rates, high test scores, and a large fraction of college graduates, upward mobility is higher for both blacks and whites but the gap between them is actually wider than in other places. In short, white boys benefit more from growing up in these areas than blacks.

There are some environments that lead to smaller black-white gaps in intergenerational outcomes: low-poverty neighborhoods with, importantly, low levels of racial bias among whites and higher rates of fathers being present among blacks. (This doesn’t necessarily need to be the child’s own father, just within the community.)

The authors of the report find that black men who moved to these better areas at a young age have higher incomes and lower rates of incarnation as adults. The problem is that fewer than 5% of black children currently grow up in areas with a poverty rate below 10% and more than half with fathers present, while 63% of white children do.

Stanford’s Chetty has previously described how he wants the Equality of Opportunity project to be able to provide the data to make better policy decisions. Too often, policies are made on a theoretical basis, but today masses of public and private data should make it feasible to devise public policy based on actual evidence. The project has already assessed the “lost Einsteins,” the millions of people who could have become innovators if they had grown up in different neighborhoods, and shown that rising inequality is leading to the end of the American Dream.

In the US, the economic inequality gap between races will never close unless policies are directed specifically at improving upward mobility for black men. The report says policies that reduce inequality for a single generation, such as temporary cash transfers, minimum wage increases, or basic income programs, isn’t enough to close the gap over time. Nor are moves to reduce school and housing segregation that don’t increase integration within schools and neighborhoods. Instead, targeted programs such as mentoring for black boys, efforts to reduce racial bias among whites, and interventions to reduce discrimination in the criminal justice hold the most promise.