For the first time, a self-driving car just caused a fatality on a public road. It won’t be the last. Every country considering approving autonomous vehicles as road-ready must now answer a question for itself in real time: what risks are they willing to accept ?

Ultimately, experts tell us, autonomous vehicles will be safer, cheaper, and more convenient. The National Highway Traffic Safety Administration estimates 103 people are killed in the US in motor-vehicle accidents every day, and more than 94% of crashes are due to driver error (pdf). Autonomous vehicle could virtually eliminate a entire category of lethal crashes (although statisticians contend the actual safety benefit remains to be proven).

After the Uber crash on March 18 claimed the life of a pedestrian in Tempe, Arizona, both Uber and Toyota paused their testing programs. Officials in states across the country are re-evaluating as well. It’s likely, though, that things will eventually resume, and the fact is that hundreds, if not thousands of deaths will result from autonomous vehicles as they take to the roads in the coming years (investigators are still determining the cause of the Uber accident).

But it’s worth putting that in perspective: the toll from self-driving cars will almost certainly pale to the carnage on our roads today, and especially what followed the introduction of the first automobiles. When new cars began rolling off US assembly lines in the early 20th century, they charged onto packed roads—and over pedestrians—wholly unprepared for them.

Detroit streets, in particularly, were chaos. In 1917, the city’s 65,000 unlicensed cars caused 7,171 accidents and 168 fatalities, 75% of them pedestrians, reports The Detroit News. Fourteen-year-olds were driving delivery trucks. One young woman who killed several people on a Detroit sidewalk was revealed to have been arrested for reckless driving 26 times.

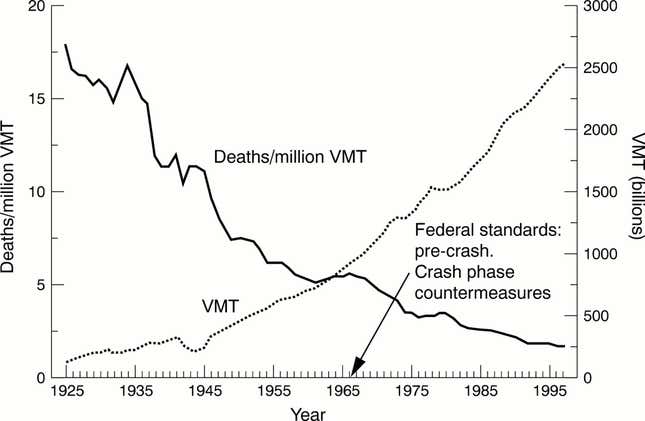

It wasn’t until 1922 that the first traffic light arrived in Detroit. States finally began requiring driver’s licenses in the 1930s. And only by the 1960s did systematic motor-vehicle safety efforts such as seatbelts arrived nationwide, along with the formation of federal agencies charged with enforcing standards. Change was slow to come, but it brought the death rate from around 25 per 100 million vehicle miles traveled (VMT) in 1921 to around 1.18 in 2016—a 93% drop.

Self-driving cars haven’t driven enough miles to prove they are safer than human drivers yet, although that’s the expectation. While they are far more strictly regulated today than their automotive predecessors, neither regulators nor companies have explicitly said how much risk is too much. Companies pushing to deploy the technology have convinced government agencies to grant approval for public testing while reassessing after accidents.

But it may turn out that Americans are unwilling to accept from machines what we have come to expect from humans. In 2016, University of Wisconsin researchers tested our tolerance of mistakes by artificial intelligence. They asked 160 college undergraduates to forecast scheduling for hospital rooms, an unfamiliar task. Help was provided by an “advanced computer system” or a human specialist in operating room management. Trust in both sources started off the same. Then, both the human and the computer started making a series of mistakes. Computer consultations fell from 70% to less than 45%, while human advisors were essentially forgiven. Researchers saw only about a 5% drop in how often participants relied on their human advisor after the error.

When entrusting our lives to self-driving cars, our instinct may be to trust humans’ mistakes rather than those of machines.