Before he would have to decide whether major oil companies could be held liable for climate change, William Alsup wanted to get some facts straight.

Alsup, who studied engineering and has a degree in math, is a federal judge with a reputation for probing for scientific details. The Verge called him a “lifelong geek.” In 2012, he presided over Oracle v. Google, a case fought over whether Google had illegally copied code from Oracle for a function called rangeCheck. Alsup revealed during the case that he writes code in his spare time. “I have written blocks of code like rangeCheck a hundred times or more,” he said from the bench. “I could do it. You could do it. It is so simple.”

Now, he’s presiding over a case in the US District Court for the Northern District of California that will decide if San Francisco and Oakland can hold Chevron, ConocoPhillips, Royal Dutch Shell, BP, and Exxon Mobil liable for the effects of climate change. At issue is whether oil companies can be held responsible for the effects of climate change, given the evidence they knew fossil fuels were driving climate change decades before the general public started to catch on, and continued to try to persuade the public that nothing was wrong. (Exxon, meanwhile, is counter-suing the cities right back.)

Perhaps judge Alsup feels a little more out of his depth here than at a coding trial; in early March, he asked for lessons. He submitted eight basic climate questions, and requested that both sides give him a tutorial.

Bloomberg called the judge “a kid who loves science class.” Before the tutorial in court, he watched National Geographic documentaries on volcanoes and the Great Barrier Reef. He even dressed the part: “I wore my science tie today,” Alsup said from the bench, according to Bloomberg. “Look, there’s the sun. There’s the Earth. I hope someone noticed.”

What followed was a sprawling science lesson. “This will not be withering cross-examinations and so forth. This will be numbers and diagrams, and if you get bored you can just leave,” he told the assembled press on the day of the tutorial. No one left, according to Science magazine.

Alsup “interrupted each presenter many, many times to get clarification, to dissect a chart or graph, or to ask additional questions,” according to the Union of Concerned Scientists. He was clearly deeply engaged, and the banter at times got painfully wonky:

Myles Allen, from the University of Oxford, was one of three scientists presenting for the cities’ side. He gave a history of climate science, and at one point did what Science called a “chicken dance” to show how carbon dioxide traps heat, spreading his arms out in what the Verge called “a wobbling motion” to “describe the motion of C02 molecules when they absorb infrared radiation.”

Alsup’s questions ranged from specific to big picture: If it’s true humans expel CO2 when they breathe, he asked, could the increase in human population over the last century be responsible for climate change? And if plants convert that CO2 to oxygen, why can’t they just handle the increase in CO2?

Allen explained that, yes, humans breathe out CO2. But that volume of emissions has nothing on fossil fuels. Plus, emissions can be traced directly to different types of fossil fuels, so we know where they’re coming from:

And plants can only absorb so much:

Chevron put forward their lawyer Theodore Boutrous, who said the company is in agreement with a UN Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change report from 2013.

Then Don Wuebbles, a University of Illinois climate scientist who led the US’s National Climate Assessment and contributed to the IPCC report, took the stand to point out that 2013 report is no longer up to date.

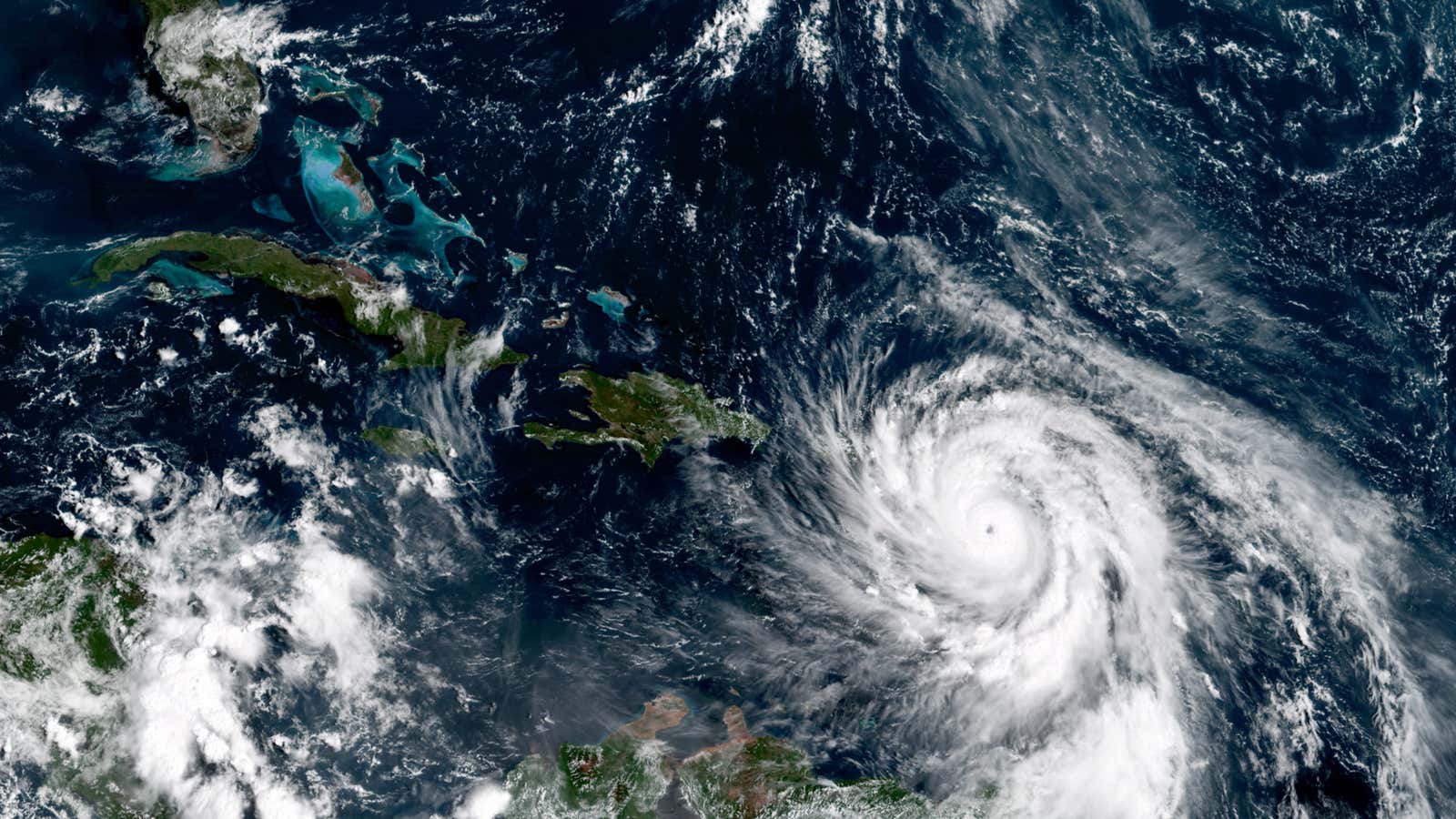

Wuebbles explained that the science on the impacts of climate change has advanced significantly in the last five years. We now know sea-level rise will likely be worse than we thought, Antarctica’s ice sheets are less stable than we believed before, and we can now link the severity of individual weather events to climate change.

Still, this was a significant moment. It’s the first time Chevron has said on the record that it does believe humans caused climate change, even if it believes it shouldn’t shoulder the blame. “Chevron accepts what the IPCC has reached consensus on concerning science and climate change,” Boutrous said. “It’s a global issue that requires global action.”

Chevron was the only fossil fuel company named in the lawsuit who gave its position; Alsup closed the day in court by saying he would give the other companies two weeks to object to anything the Chevron lawyer said before holding another hearing. “You can’t get away with sitting there in silence,” he said.

The cities want the companies to pay for infrastructure like sea walls to stave off the effects of a warming climate, while the companies have asked the court to dismiss the lawsuit, claiming the harm is “speculative.” Whatever the court’s next step in this suit may be, the judge got both sides on the record acknowledging the science.

In a moment when it feels like climate science is often regarded as a matter of political opinion, rather than scientific consensus, having a judge approach the issue like a curious student is a breath of fresh air.

After all, climate change will certainly be no more or less damaging—and the cause no more directly related to human activity and fossil fuel combustion—whether anyone believes in it or not. Or, as climate scientist Katharine Hayhoe put it to Wired in December, “The true threat, however, is the delusion that our opinion of science somehow alters its reality. If we say we don’t believe in gravity and we step off the cliff, we’re still going down.”