One of the most active student clubs at Michigan State University meets every other Wednesday in a room above a buzzing cafeteria.

This club doesn’t organize intramural sports or plan keg parties or produce the yearbook. It pores over dense financial documents to examine how the university handles its money. One kind of risky deal they unearthed, the students in the group say, cost the school more than $130 million at a time when tuition was increasing much faster than the national average.

University of Michigan lecturers and graduate students negotiating for higher salaries and benefits have been drilling into that institution’s operating budget, finding what they say is a $377 million surplus it’s enjoying from their comparatively low-paid labor.

The University of Michigan isn’t the only institution that’s being scrutinized. In Colorado, adjunct instructors at community colleges have used public-records law to dig through data showing vast disparities in pay. They say this research shows that there are almost four times more part-time than full-time faculty members but part-timers collectively get about one-tenth of the money the colleges spend on instruction.

This is what scholars do, said Caprice Lawless, second vice president of the American Association of University Professors chapter representing faculty at the Colorado community colleges: They look more deeply into things. “The default position, of course, among academics is to research issues and to publish findings.”

Seldom has this level of attention from students and employees been so focused on the finances of their own campuses. It coincides with what polls disclose is falling public confidence in higher education. And given the results, it seems likely to create more, not less, mistrust.

“This is going to raise questions about the legitimacy of our whole model, and I’ll be glad to see that,” Ian Robinson, president of the Lecturers’ Employee Organization at the University of Michigan, said in the union’s office near the campus in Ann Arbor.

At many institutions, financial data being scrutinized in this way increasingly suggest that model is built on low-paid, part-time instructors working under top-heavy bureaucracies.

The students and lecturers who are drilling into university finances charge that they are spending smaller proportions of their investment returns on financial aid and faculty salaries while larger proportions are funneled into questionable investments.

“Students want to know where their money is going. When we break it down for them, they’re shocked,” said Andrea Cardinal, a lecturer who teaches art and design at the University of Michigan, which she also attended. “I was as well.”

This appears to be fueling a spiraling cycle of scrutiny.

“People just didn’t have an understanding of where the money was going, and now that they do it makes them really angry,” said Brigid Kennedy, one of the leaders of the student group at Michigan State that’s looking at that institution’s finances.

Universities, which once were given the benefit of the doubt, say the people scouring their books are misinterpreting what they’re seeing, sometimes for their own purposes. They say students and employees haven’t asked administrators for explanations of the data.

“It’s interesting that students here at MSU are concerned about investments but haven’t once reached out to our investment office, requested information or asked for a meeting,” said Philip Zecher, Michigan State’s chief investment officer.

Higher education has become a popular public target. Fifty-eight percent of people polled by the think tank New America said colleges and universities put their own interests ahead of those of students. About the same proportion in a Public Agenda survey said colleges care mostly about the bottom line, and 44% said they’re wasteful and inefficient. And a Gallup poll found that more than half of Americans have only some, or very little, confidence in higher education.

What students and employees say they’re finding deep in the financial ledgers isn’t likely to help.

“The numbers are surprising and important because they’re true,” said Lawless, who teaches academic writing and freshman composition at Front Range Community College. “It’s not a question of not trusting. It’s about holding institutions accountable.”

In looking at the investments made, a network of student groups affiliated with the Roosevelt Institute, including that chapter at Michigan State, report (pdf) that 19 public and private universities it studied lost a collective $2.7 billion as of 2016 through a complicated financial instrument called an interest-rate swap. The institute is a liberal think tank associated with the Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library and Museum that focuses on economic policy.

Interest-rate swaps are used when universities issue bonds to pay for new construction. The universities pay banks a fixed interest rate on the bonds, while the banks pay universities a variable interest rate. If the variable rate rises above the fixed rate, the university makes money. If it falls below, the banks do.

In hindsight, said Walter Hanley, another leader of the Michigan State student group, “That’s just a strange bet to make as a public institution.”

In fact, interest rates were dragged down by the economic recession, costing Michigan State alone $130.2 million by 2016, including nearly $18 million in termination fees, the students contend—at the same time that tuition was rising significantly faster than the national average. (The university disputes this and says that the figure the students reported was merely where things stood in 2016, on paper; as the economy has rebounded, it says, its losses on interest-rate swaps have proven to be much lower.)

“Our goal is just to see that the university is using best practices,” said Chris Olson, who’s part of a similar group of students at the University of Michigan. That school, its students say, lost nearly $86 million in interest-rate swaps through 2016. “They did lose a good amount of money that could have been used in another way. We decided this was something we wanted to make noise about.”

Michigan spokesman Rick Fitzgerald said the students there never spoke to university administrators either, that the penalties included in the estimate of losses were never actually paid, and that interest-rate swaps “are not inherently bad. This is a prudent way to manage debt, like converting your home mortgage from a variable rate to a fixed rate as interest rates start to rise.” He said interest-rate swaps have saved the university money over time on debt payments.

Higher-education institutions generally have had lackluster results in their investments. Endowment returns were 12.2% in the last fiscal year, according to the National Association of College and University Business Officers and the Commonfund Institute; that’s after falling 1.9% in 2016 and badly trailing expectations over the last decade, with the 10-year return averaging 4.6%.

Nor will most disclose what they’re paying in management fees for this. Students at Michigan State and other schools have appealed to find out, without success. Michigan State said that, unlike for people who sign on with personal investment managers, its management fees are not calculated separately but simply factored into gains or losses. The University of Michigan successfully lobbied in 2013 to shield much information about fund performance from the state’s open-records law.

“It’s a pretty oblique process and I would say the university wants it to be that way,” said Olson over coffee in Ann Arbor.

The students at these universities in Michigan have done something else almost unheard of in this era of political polarization: gotten the College Democrats and College Republicans to work together, in this case on a demand that students and faculty be added to the universities’ boards of trustees. In Michigan, that would require a constitutional amendment.

“We want to see greater transparency in how they spend our money. And it is our money, most of it,” since such a large percentage of the budget comes from tuition, said Manon Steel, another student at Michigan State, in that conference room above the cafeteria. “The argument for an elected board of trustees is that the state pays for the school, which is no longer the case. We pay for the school.” Michigan underwrites a comparatively low 15% of its universities’ budgets, leaving the rest to be covered by tuition.

Students and employees aren’t the only people scrutinizing universities’ financial information. A two-year investigation by the Detroit Free Press found that the University of Michigan invested much of its $10.9 billion endowment in companies controlled by donors and alumni. The university disputed the amount cited by the newspaper, but said that 2% of its endowment, or nearly $220 million, is in funds managed by members of its Investment Advisory Committee.

“We would be foolish not to reach out to these alumni for their high-level advice and, when it fits with the university’s investment approach, to invest in their well-managed funds,” the university said in a statement. It added: “Potential or perceived conflicts are a part of every business environment.”

The endowment generated $325 million last year that was used for salaries, financial aid, and other costs, the school said. But like many other universities, Michigan has reduced the share of the endowment that goes to this purpose, from 5% to 4.5%. The difference is enough to pay the full tuition, room and board of 280 students, the Free Press said.

Other kinds of nonprofits are required to spend at least 5% of their endowments on operating costs, and there have been bipartisan calls in Congress for universities to be subjected to that rule. The average so-called “effective spending rate” at universities is 4.4%, NACUBO and Commonfund report.

Yet another group comprised of labor unions, students and advocacy groups has been analyzing universities’ investments in hedge funds, which these activists—who call themselves Hedge Clippers—say are bad risks with high fees.

Of the money that is being spent at the University of Michigan on daily operations, $85 million went to salaries and benefits of lecturers, the 1,700-member lecturers’ association found. (“UM Works Because We Do,” shout the placards leaning against a wall in the union office.) But the university collected $462 million from the tuition students paid to take their classes, leaving what the lecturers contend is a $377 million-a-year surplus.

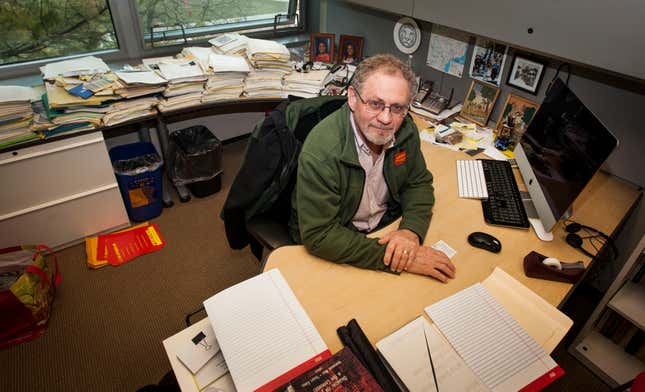

“Over time we’ve become more convinced that the university operates more and more as a for-profit business and they treat us like commodities,” said Robinson, a lecturer in sociology who enlisted an economist from a neighboring university to comb through the financial figures. “If that’s the way it’s going to be, we’ve got to use more effective tools to make our case.” As contract negotiations loomed, he said, “we wanted to be able to talk about the university’s ability to pay.”

The university did not dispute those figures but said there isn’t any surplus. That $377 million pays for classrooms, heat, light, supplies, support staff, libraries, administrative support and other services, it said.

Among other things, the lecturers have also calculated that tuition over the last 14 years at Michigan has increased 89% while the minimum salary for a starting lecturer rose 11%. Armed with information like this, University of Michigan lecturers have voted on Wednesday (March 28) four-to-one to authorize a strike if ongoing negotiations for a new contract break down, according to an emailed statement.

“It’s really interesting to follow the money,” said Tony Hessenthaler, a lecturer who teaches romance languages and literature. “The information is out there if you’re willing to look at it. People generally thought the university had their best interests at heart.”

The university said across-the-board increases for lecturers on the flagship Ann Arbor campus—not just the minimum for those just starting out—have risen 26% in the last 10 years, and some lecturers have gotten more than that.

Still, the minimum starting salary for an entry-level lecturer in Ann Arbor is $34,500 for the eight-month academic year, the university confirmed, which annualizes to much less than the $89,186 the nonpartisan Economic Policy Institute says a family of four needs to live there, and which Cardinal and others said they’re not shy about sharing with their students.

“‘You make how much?’” the students ask her, said the graphic design instructor. “The more the students know about where their money is going, the better.”

There’s similar defiance in Colorado, where the part-time faculty have woven financial figures—some obtained through public-records requests—into a tongue-in-cheek coloring book with puzzles challenging readers to match the six-figure salary with the community college president who earns it.

“We do these things because they offer a countervailing truth to the unbelievably sunny spin offered by these institutions and their lobbyists,” said Lawless. “They carry on as if, ‘Gosh, we would love to pay our faculty more, but our funding just doesn’t allow it.’ A generation has been listening to someone in a suit and thinking, ‘Well, that must be true.’”

Truth is still not entirely a settled matter in these cases, with universities and their critics volleying the numbers back and forth. But Steele said that’s not the point.

“There’s something to be said for the administration just knowing that we’re watching,” she said.

This story was produced by The Hechinger Report, a nonprofit, independent news organization focused on inequality and innovation in education. Sign up here for their higher-education newsletter.