Fifty years ago, on April 4, 1968, Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated in Memphis, Tennessee. The murder of the civil-rights advocate at age 39 rocked a country where memories of the slayings of John F. Kennedy and Malcolm X remained fresh. And just months later, Robert F. Kennedy would be gunned down in Los Angeles.

King’s murder fueled decades of conspiracy theories and allegations of a government coverup from those who believe James Earl Ray, the man who initially confessed, couldn’t have acted alone. The doubts had echoes of those that surround JFK’s killing to this day: Was Ray a lone gunman on a self-propelled mission? Or the unfortunate patsy in a massive conspiracy?

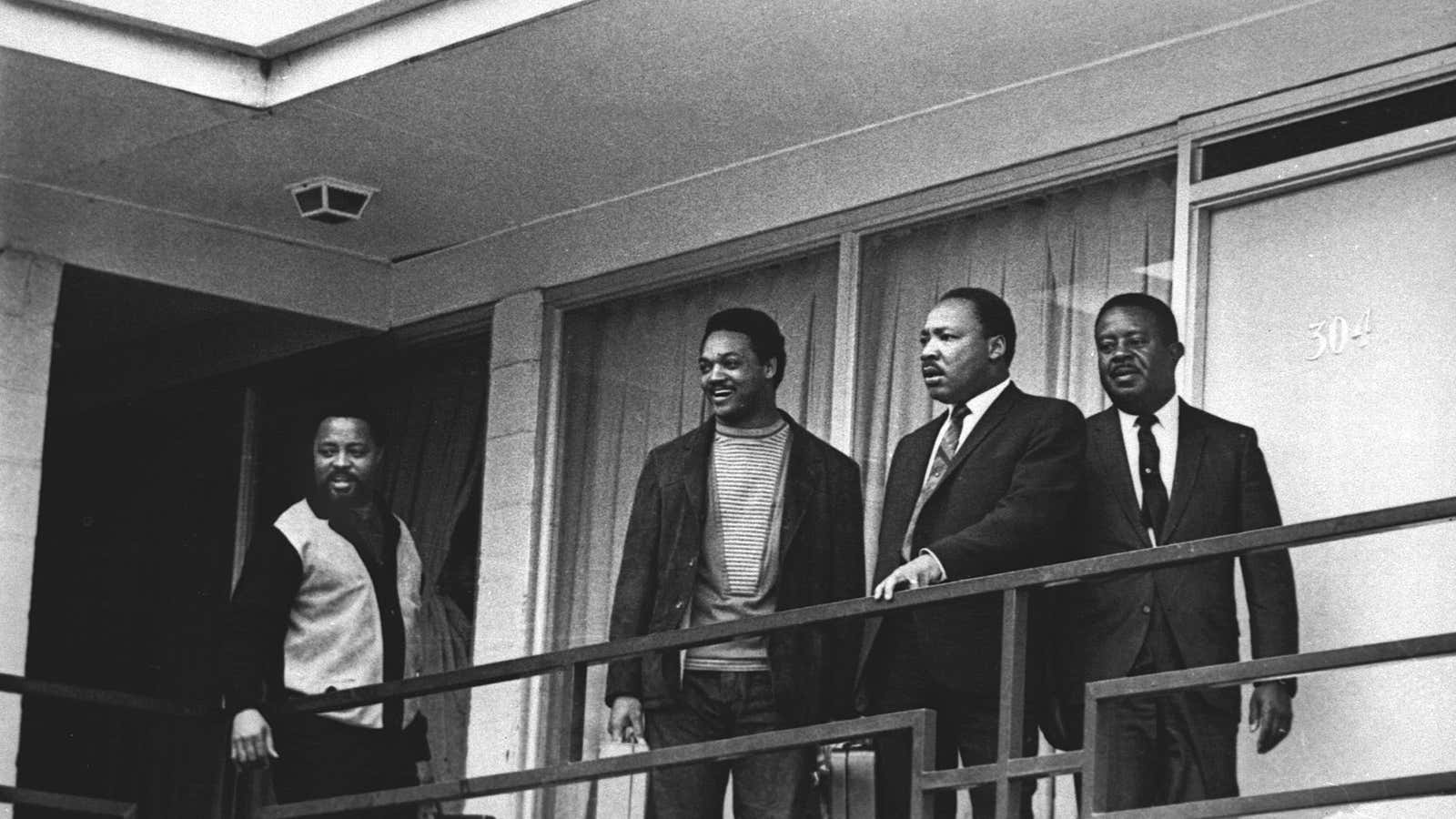

Five decades later, according to some of those closest to the case—including King’s own family—the question of exactly what happened on the second-floor balcony of the Lorraine Motel that April 4 has still not been definitively answered.

Martin Luther King Jr.’s mission in Memphis

King was in Memphis to support the city’s striking sanitation workers ahead of a march he was planning in Washington on behalf of poor Americans. He delivered what was to be his final speech at the Mason Temple Church in Memphis on April 3, the night before he was killed, with words that eerily foreshadowed his death:

Just after 6pm the next day, King was hit in the neck by a single bullet at the Lorraine, where he was known to stay when visiting the city. He was pronounced dead at St. Joseph’s Hospital about an hour later.

James Earl Ray’s capture and confession

Fingerprints on a rifle, scope, and pair of binoculars found near the scene, as well as in the bathroom of a boarding house across the street from the Lorraine—from which police believed the shot had been fired—matched a single suspect: James Earl Ray.

Ray was a low-level criminal on the run after escaping from a Missouri prison in 1967 while serving time for a holdup. Many of the basic facts lined up: Ray had purchased a Remington .30-06 Gamemaster rifle (the same make and model used to kill King) in Birmingham, Alabama six days prior, and had been renting a room in the Memphis boarding house under an alias at the time of the murder.

An international manhunt led to his arrest in London at Heathrow Airport on June 8, 1968. Ten months later, Ray pleaded guilty to assassinating King to avoid the death penalty. He signed a detailed confession.

Ray was sentenced to 99 years in prison and because of the guilty plea, no testimony ever was heard in court. (Ray and seven other inmates escaped from prison for three days in June 1977. He received an additional year on his sentence).

Allegations of a conspiracy

Three days after his guilty plea, Ray tried to recant his confession, saying he was the victim of a wide-ranging conspiracy and that his lawyer had coerced him into pleading guilty.

Ray said that while on the run in Montreal in 1967, a man he knew only as “Raoul” lured him into a small gun-running scheme, and instructed him to buy the rifle in Birmingham as well as rent the room in the Memphis boarding house. Ray claims to have given Raoul the rifle before the King murder, and other than that, had no involvement in the assassination. He says he had no prior knowledge of any plot to kill King.

Ray’s motion was denied, as were his many other requests for a retrial over the next 29 years, before he died in prison in 1998.

A 1977 US House Select Committee investigation put forth the theory that Ray assassinated King in the hope of collecting a reward from the supporters of then-presidential candidate George Wallace, though there was little supporting evidence.

John Campbell, district attorney for Shelby County in Tennessee, spent years investigating the case and is certain of Ray’s guilt. “I’m not saying he didn’t have help. But he didn’t have the FBI, the CIA, the Memphis police or the mafia,” he told the Washington Post in March.

The King family and their doubts

The FBI took the lead in the investigation of King’s murder, which became the primary basis for his family’s distrust of the official version events.

The agency had spent the previous decade working to discredit King and his supporters through constant surveillance, disinformation, harassment, and even open criticism from FBI director J. Edgar Hoover. Given this history, King’s family maintains the FBI couldn’t have led a unbiased investigation, alleging at the very least negligence, and at the very most a government conspiracy and coverup.

In 1997, King’s son Dexter met with Ray in prison. “I just want to ask you, for the record, did you kill my father?” Dexter asked. “No, no, I didn’t, no. But like I say, sometimes these questions are difficult to answer, and you have to make a personal evaluation,” Ray responded, hinting at a possible conspiracy. King told reporters he and his family believed Ray’s story and supported his efforts for a retrial.

After Ray’s death in 1998, Coretta Scott lamented that “America will never have the benefit of Mr. Ray’s trial, which would have produced new revelations about the assassination…as well as establish the facts concerning Mr. Ray’s innocence.”

King’s surviving children aren’t in total agreement about the true nature of their father’s death (whether they believe Ray’s story, Jowers’ confession, or something else entirely), but all of them say they are certain Ray didn’t fire the gun that killed King.

Coretta Scott King vs. Loyd Jowers

The FBI maintains its original conclusion and denies all allegations of a conspiracy or coverup, but unanswered questions still linger about King’s final moments and details of the investigation.

For instance, witnesses (including a New York Times reporter) reported seeing a man in the bushes beneath the boarding-house bathroom, but for some unknown reason, Memphis Public Works cut down the bushes the next day, destroying any potential crime scene. King’s usual Memphis Police security detail was also mysteriously withdrawn on the day of the assassination.

Then, there is Loyd Jowers, owner of a bar on the first floor of the boarding house, who told ABC-TV’s Primetime Live in 1993 that he had been involved in a conspiracy to kill King that involved organized crime and the US government. Jowers said he hired a crooked Memphis police lieutenant to commit the murder as a favor to a local mobster friend and was paid $100,000.

In 1999, the family filed suit against Jowers, seeking to get more information into the public record. After hearing four weeks of testimony from over 70 witnesses, a Shelby County jury unanimously found Jowers and unnamed “others, including governmental agencies,” responsible for King’s death. The verdict didn’t change much, however, as the civil suit didn’t reverse Ray’s conviction and the King family had only sought a symbolic $100 in damages as proof they weren’t motivated by financial gain.

The trial “relied heavily on second- and third-hand accounts,” the Los Angeles Times reported, and both the jurors and judge (a year away from retirement) dozed off during testimony. Jowers never took the stand and only provided his account in depositions and unsworn video statements.

Partly based on Jowers’ claim, the King family successfully petitioned the administration of president Bill Clinton to have the US Justice Department reopen the case in 1998. The subsequent investigation led to the same conclusion as the original: Ray alone was guilty of the murder and there was no conspiracy.

Barry Kowalski, the civil-rights special counsel who led the federal investigation, said that Jowers had repeatedly changed his story and wasn’t credible. It was also revealed that Jowers had confessed to fabricating his claim in the hopes of receiving a $300,000 book deal.

“Our thorough investigation,” Kowalski said recently, “just like four official investigations before it, found no credible or reliable evidence that Doctor King was killed by conspirators who framed James Earl Ray. Twenty years later, I remain absolutely convinced this well-supported finding is correct.”

The legacy of King’s assassination

For many, King’s assassination effectively marked the end of the civil-rights era in the United States. The white backlash he had foreseen would come to full flower in electoral politics. And his murder helped radicalize many disillusioned activists who felt their hopes for nonviolent change were over, and further fueled the rise of the Black Power movement that showed increasing disdain for King’s pacifist approach.

Many of the documents from the FBI’s original investigation remain classified and won’t be released to the public until 2027.

King’s legacy and influence can still be felt today as a contentious political climate and renewed spirit of activism inspires millions of Americans to march peacefully in Washington to fight for everything from gender equality to science-based policy to gun-reform legislation.

Bernice King recently told 60 Minutes that despite the violence and controversy surrounding her father’s death, she doesn’t view it as a tragedy: “Our world is in a better place because our father gave his life.”