This is episode one of the series “The ID Question,” from How We Get To Next.

Siddharth Singh was supposed to be in school this year. Instead, the five-year-old is stuck watching television all day in his family’s small house in the slums of West Delhi, India. His mother, Radha, tried to get him into the local government school, but Siddharth can’t get the education he’s entitled to—because he doesn’t have an Aadhaar card.

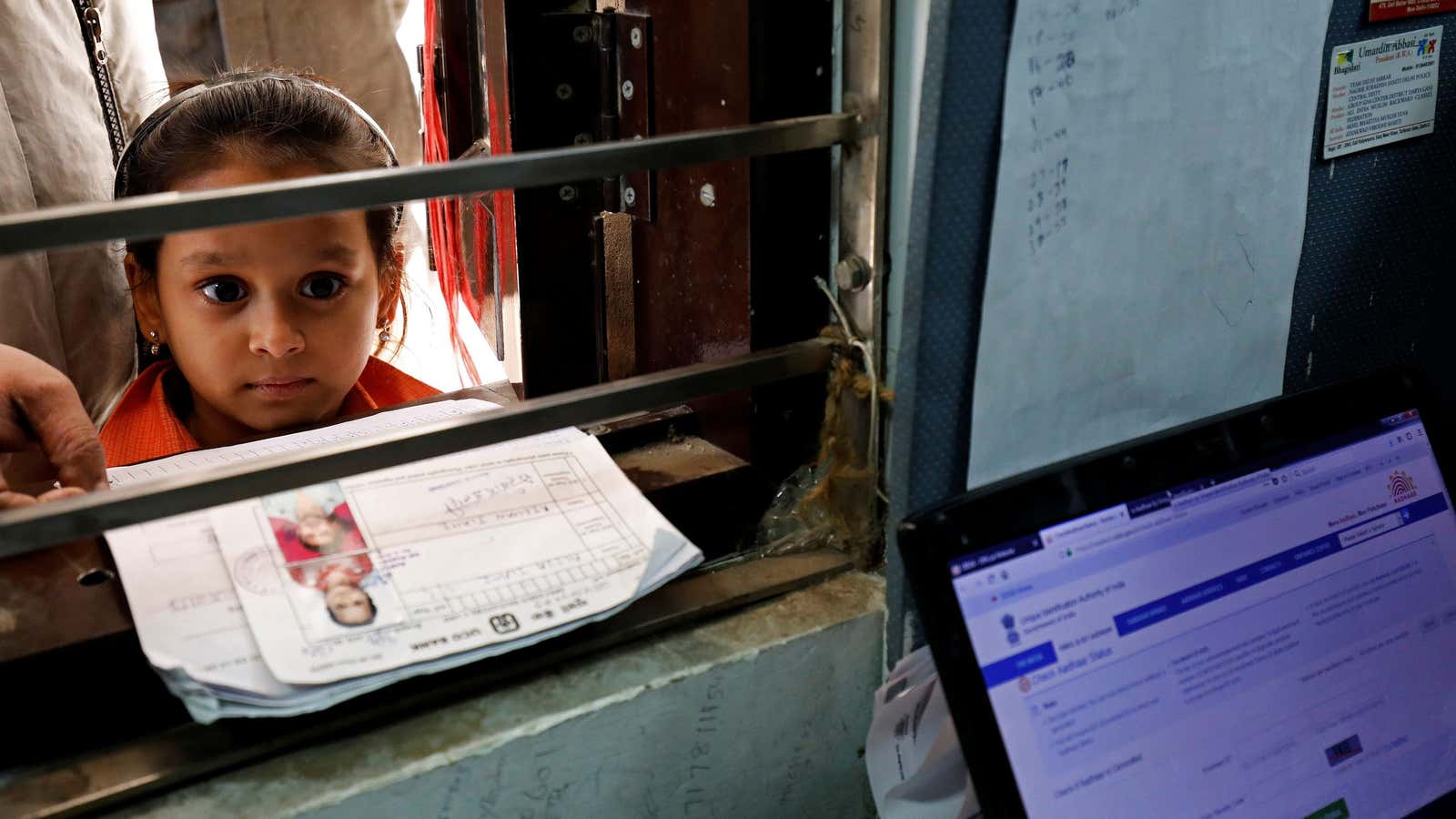

Aadhaar is the world’s largest, most ambitious digital identity scheme, and its cards are central to daily life across India: they drive news cycles, spark political debates, and are the subject of conversation from Mumbai to Kolkata. Aadhaar, which was launched by the Indian government nearly a decade ago, aims to give each of the nation’s 1.3 billion citizens an official, verified identity, eventually making it the largest biometric ID system in the world.

In the past decade, the scheme has exposed a host of issues, from identity theft to the erosion of privacy rights. Poverty is widespread across India, and Aadhaar’s role in giving—or denying—people access to government services has sparked a great deal of controversy. Ideally, one simple system should grant everyone the rights and services that they’re entitled to. But if you’re locked out of that system, you can lose access to everything.

Delhi is a city full of migrants. Siddharth’s mother and his grandmother, Laxmi, both emigrated from Nepal more than 30 years ago. Nepalese citizens are allowed to work in India, and they don’t need ID for so-called “unorganized” work, including domestic help. But they do need ID to access welfare schemes that subsidize housing, food, and fuel, and ID is a necessity if they want to try to get better-paid work, open a bank account, or buy a house—the things people need to climb above the poverty line.

Radha and her husband, Joginder, both have Aadhaar cards. After years arguing with officials over older forms of ID like ration cards, Aadhaar’s simplicity and legitimacy are a welcome relief. But getting Siddharth his card was more complicated—because they never applied for a birth certificate when he was born.

“We left it too late,” says Radha. “And now it will cost anywhere between Rs 3,500–6,000 (about $50–100) to get the certificate made. It’s such an additional, unnecessary expense.” In India, a lost or damaged birth certificate can leave you in a catch-22: birth certificates are often the way to “seed” other kinds of ID, but without those other forms of ID, you can’t replace your birth certificate.

Siddharth’s older sister, Sia, goes to a private school. There’s a perception among many in India that private schools—which teach in English, rather than the less-prestigious Hindi—are better than government schools. The Singhs can only afford to send one child to private school; unless their finances change dramatically, they need to rely on the government for Siddharth’s schooling—but the government doesn’t think that Siddharth exists.

The Singhs’ experience is a common one—and one that predates Aadhaar. People so often fear losing hard-won ID documents that they tend to store them with their most valued possessions—both because a lack of ID can mean being cut off from vital services, but also because of India’s notoriously opaque and inefficient bureaucracy. Re-registering with a government authority or getting a duplicate ID is a frustrating process: days of waiting, jumping through hoops, or even paying bribes.

Today, something as simple as a missing document or a faulty fingerprint reader can mean an elderly person is denied a vital pension, or a child, like Siddharth, is denied an education. Many essential services are currently linked to Aadhaar, and many more will be in the near future. India is relying on the comprehensive reach of this universal digital ID system—but what about the people who fall through the cracks?

Each individual Aadhaar card and its unique identity number is part of an enormous digital system. Every record in the centralized database includes a person’s basic demographic and biometric information, including a photograph, ten fingerprints, and two iris scans. This data is collected and managed by the Unique Identification Authority of India (UIDAI), which was founded in 2009 and was given stronger legal powers under a 2016 law passed by the government of Prime Minister Narendra Modi.

As of October 2017, India had issued 1.18 billion identity cards. There are big differences between states, but across the entire country, Aadhaar now covers 99% of the adult population, 75.4% of children between five and 18 years old, and 41.2% of children between zero and five. The system is meant to make it possible to “target delivery” of essential government services; there are least 87 different schemes linked to it, including education access, pensions, scholarships for minorities, farming subsidies, school meals, and healthcare.

!function(e,t,n,s){var i=”InfogramEmbeds”,o=e.getElementsByTagName(t)[0],d=/^http:/.test(e.location)?”http:”:”https:”;if(/^/{2}/.test(s)&&(s=d+s),window[i]&&window[i].initialized)window[i].process&&window[i].process();else if(!e.getElementById(n)){var a=e.createElement(t);a.async=1,a.id=n,a.src=s,o.parentNode.insertBefore(a,o)}}(document,”script”,”infogram-async”,”https://e.infogram.com/js/dist/embed-loader-min.js”);

Before Aadhaar, people had to use different IDs, from birth certificates to ration cards, to access these services. The result was inconsistent and highly fallible. If the new bureaucrat behind the government office window didn’t believe you were the person on your old, tattered ration card, you wouldn’t get rations for the month. Basic tasks like opening a bank account or applying for a utility like water have been impossible for millions of Indians because they can’t prove who they are.

Aadhaar’s promise is that, by absorbing every existing kind of ID into one database, it will close gaps in service and welfare provision, and empower poor people by removing many of the barriers to escaping poverty. Since the system is completely digital, it opens up the possibility of integrating new kinds of ID that haven’t even been proposed yet—a new kind of online banking service, for example—without massive upheaval. It’s meant to future-proof the concept of official identity in India.

It could have an impact in other countries, too. The Aadhaar experiment is being studied by governments in other countries, eager to see if this system solves many of their own service provision problems. The World Bank estimates that one in seven people globally can’t prove their identity, most of whom are in Africa and Asia and are under the age of 18.

The truth, however, is more complicated. In closing old gaps in service provision, Aadhaar has opened new ones, and the system has thrown settled lives into disorder and confusion. Many of those who need government services the most are also the most likely to fall through these new gaps in the system: poor migrants, children, the rural elderly, caste and tribal minorities, the visually impaired, the physically disabled, and more.

Leprosy sufferers are a prime example: there are reports of people without fingers or sight being refused welfare payments because they physically cannot prove their ID with fingerprints or iris scans. In one village in Haryana, 65 people with leprosy reported losing their monthly rations for the same reason. There are at least 86,000 people in India with leprosy—and that’s only one illness, out of innumerable other situations that can preclude someone from being able to give the information that the system demands.

India’s vast population and dozens of distinct cultures—not to mention the wide ranges of literacy and wealth—makes a one-size-fits-all ID scheme all the more difficult to implement. For poor people, disabled people, or for people who are illiterate, the bureaucracy is tough enough to navigate—but Aadhaar compounds these existing inequalities.

In the slums of Delhi, children beg at traffic lights, or sort through landfills looking for scrap metal to resell. Sanjay Gupta, the director of Chetna, a Delhi-based NGO that works with children in poverty, has helped hundreds of these children apply for ID over the years. Their addresses are not so much homes as indicators of poverty: addresses like “Under Moolchand Flyover” or “Under IIT Flyover.”

“An Aadhaar is sort of an entry card to the dignified life,” says Gupta. “But it’s not easy to get.” Gupta acts as a child’s “introducer,” a kind of witness who can vouch for the child to a local official. But the system is entirely informal, and whether his introduction is accepted varies from officer to officer. “Aadhaar has become a very powerful document,” says Gupta. “It has left the passport behind. But [these officials] need to be trained not to refuse anyone.”

Even successfully registering for and getting an Aadhaar number doesn’t guarantee things will be easy. Opening a bank account requires proof of address—like a utility bill—but people who live in the slums are often unable to apply for utilities because they don’t have an address. All new bank accounts need to be linked with Aadhaar numbers, but payment errors are common. Gupta often hears from people who never receive money they’re entitled to, and don’t know how to challenge it. “The poor have very little financial literacy and no bank officer has the patience or inclination to explain finances to a poor person,” he says.

Of the more than 500 children Chetna has helped over the last two years, by far the most common problem was getting—and keeping—the physical Aadhaar card. “You forget that these are homeless people,” Gupta says. “They roam around in kaccha-banyan (rags). This is a document that needs safekeeping. Where will they keep it?”

Vishal and Bhavna, whose names have been changed on request, are teachers who work for a government school in Delhi. They spend their spare time working with children in the slums, helping them get ID so they can enroll in school. “It is absolute hell here,” says Vishal. “There is no water or electricity. There is no sewage connection. There are open drains. You cannot even imagine it.”

Vishal and Bhavna write letters of recommendation to try and convince officials to register children, or even whole families, with Aadhaar numbers. Many government schools have recently made an Aadhaar number mandatory for children seeking admission. Bhavna, who has been a teacher for 18 years, says she’s had to refuse 50% of applicants since the new rule was implemented. Both Bhavna and Vishal have asked their superiors not to implement the new Aadhaar requirement.

“Why do you need an Aadhaar for education for the least privileged?” Bhavna asks. “Imagine a daily wage laborer who has moved here from Bihar with his family. He has nothing and probably lives in a shack. He has no papers. He can barely fend for himself and his family. Whatever he earns in one day lights the cookstove for dinner at night. If he has to spend three to four days running around getting an Aadhaar card, it will mean that he probably doesn’t eat on those days. Would you do it?”

The new rule is all the more frustrating because there is an open question over whether the schools are breaking the law in making Aadhaar compulsory. The first successful case to be brought to the Supreme Court, in 2012, was won on the basis that the system violated the fundamental rights of privacy and equality—different social groups being denied services they are entitled to—and that the government has a constitutional obligation to provide free education to all children between ages six and 14.

Since then there’s been a running battle between civil society groups and the government. Compulsory Aadhaar in schools was challenged in the Supreme Court again in October 2015, in a case brought by a coalition of government school teachers, parents, parents’ associations, and NGOs. The plaintiffs won, and the ruling clearly stated that access to welfare services should not be tied to Aadhaar registration. But the federal government continues to introduce compulsory Aadhaar registration for all kinds of things that exist in a legal grey area, from senior rail passes to applying for government jobs.

At the state and city level, many schools still demand Aadhaar cards, and some have proposed making Aadhaar compulsory to receive free school meals. India’s Supreme Court has repeatedly reiterated that its earlier ruling still stands, leading to an ongoing game of cat-and-mouse between the executive and judicial branches of government—with the country’s most disadvantaged citizens caught in the middle. And in a country with widespread illiteracy and a broad range of languages, mixed messages about whether Aadhaar is mandatory or not have led to mass confusion.

The Indian government provides small scholarships and stipends to groups like caste and tribal minorities, or female students—but you need a bank account linked to Aadhaar to receive it. Many teachers have had to take up what is effectively an unpaid second job, handling distressed parents upset about their struggles trying to put their children through “free” school. “We have to send reports on how many identities and bank accounts have been linked to Aadhaar every single Friday,” says Vishal. “This is not a teacher’s job, is it?”

The story of Aadhaar is increasingly the story of identity systems across the globe. In the coming decade, identity will become increasingly digitized, centralized, and integrated with our lives online. As other countries—particularly lower income ones—look to Aadhaar as a potential model for the future, they’re watching the system’s growing pains as well.

Throughout history, identity systems—from the first paper passports to modern digital programs like Aadhaar—have been used to define people in different ways. Who’s eligible for government welfare, and who isn’t; who gets treated with humanity by the state, and who doesn’t. They define individuals as either acceptable or unacceptable in the eyes of people with power.

Over the course of this series, we’ll be examining modern identity systems and the individuals struggling with them, from asylum seekers in Ireland to indigenous tribes in Japan. Today’s identity systems have the potential to reach more people—and, in turn, to help more people than ever before. But what happens when these systems make lives worse? Can we design a system that ensures that no one falls through the cracks?

This article was originally published on How We Get To Next, under a CC BY-SA 4.0 license. Read more about republishing How We Get To Next articles. Sign up to the How We Get To Next newsletter here.