In the ever-deepening wake of the Cambridge Analytica scandal, where nearly 90 million Facebook users had their data unknowingly harvested by the data company hired by the Trump campaign, the social network has been under increasing scrutiny. There are calls for regulation on how Facebook (and other sites) can access and manage its users’ data, and CEO Mark Zuckerberg will testify before the US Congress to discuss exactly what and when he and his company knew about this data breach.

At the same time, the European Union is about to enact the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), which will give internet users far greater control over the data that internet companies have on them, and some are wondering if Facebook will introduce similar protection for its US users. (Facebook itself has been a bit wishy-washy on the matter.)

With this backdrop, Facebook has already taken a big hit. It has lost nearly $100 billion in market value since news first broke about Cambridge Analytica’s activity, and there are concerns users may leave in droves—the company says they’re not, though there was already a minor exodus of US users before this scandal. Zuckerberg also said in a call with reporters yesterday that the cost of improving security and privacy on the site will likely rise for the next two years.

Right now, the overwhelming majority of Facebook’s revenue comes from advertising in the North America and Europe. Last year, it earned an average of $84.41 for each North American user, and $27.26 per European user, and the two areas combined accounted for around 88% of its total revenue.

But what happens to Facebook if its advertising business gets regulated into the ground in Europe and North America? What about its hundreds of millions of users on the other side of the world, who haven’t been directly affected by the Cambridge Analytica scandal or the Russian bot scandal, and might not particularly care what’s going on in the West? (Although there is mounting evidence that Facebook may have been used to manipulate elections in other countries.)

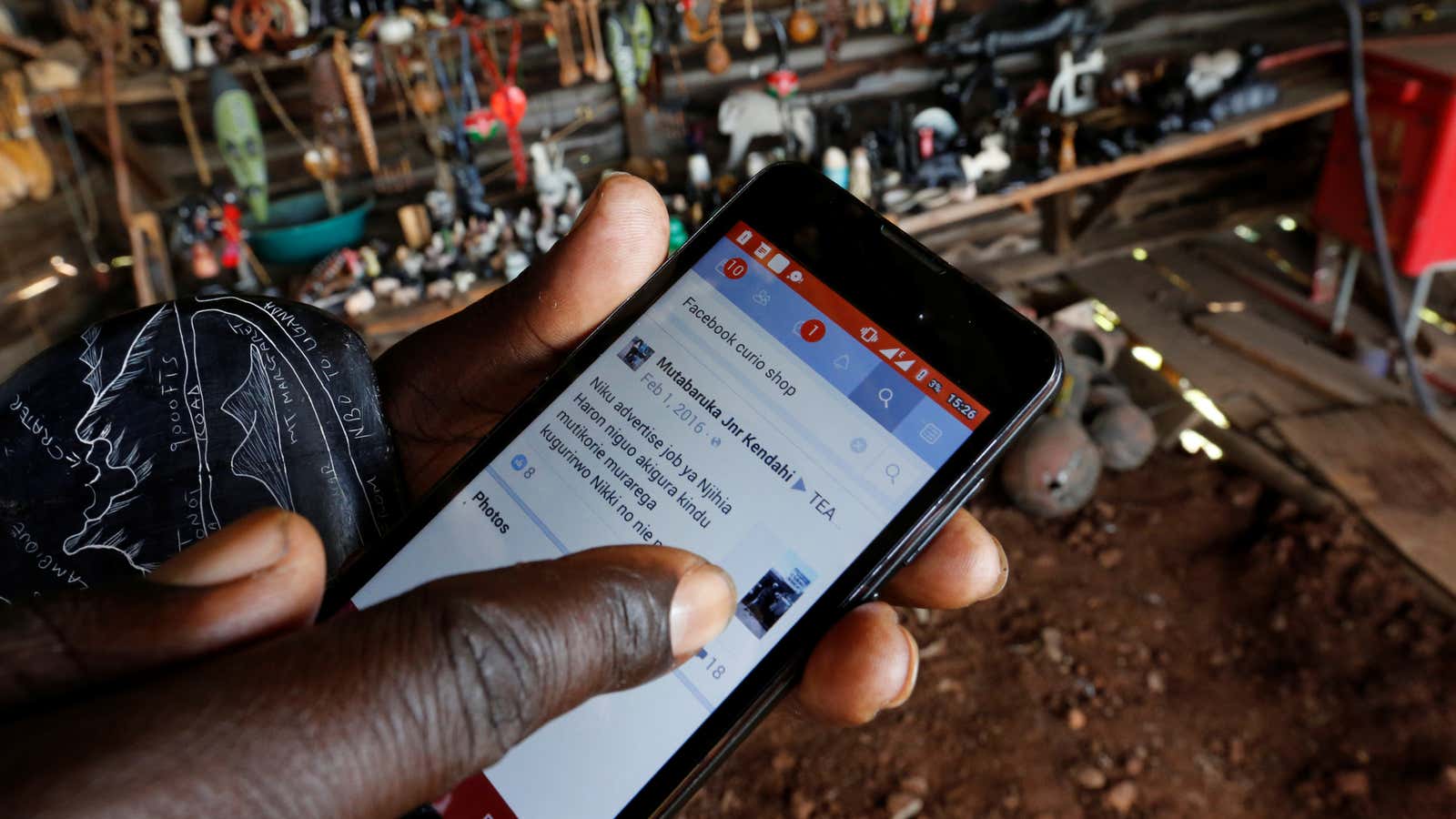

As my former colleague Leo Mirani once eruditely uncovered, for millions of people in developing countries, Facebook is the internet, and many don’t even realize they’re on the internet when they’re using Facebook’s services.

Through its main app, Instagram, Messenger, WhatsApp, and the Lite versions of its apps, Facebook has a range of offerings that people use to run their lives. In many countries, WhatsApp has become what WeChat is in China, a digital hub through which all socialization and commerce is done. Patients talk to their doctors through it in Brazil; it accounts for nearly half of all internet traffic in Zimbabwe; and it’s the most popular social networking app in 109 countries across the world. In India, Facebook recently started testing a payments option, where users can connect with their bank to send and receive money through the app.

Facebook has roughly 1 billion daily users on its main app outside of the West, and WhatsApp itself has over 1 billion total users. That is a very, very large group of people. And it’s also where Facebook is still growing through its various apps. User growth has stalled out in Europe over the last few quarters at around 1% quarter-over-quarter, and in the US it just recently dropped. The majority of its growth is coming from the Asia-Pacific region. It’s likely that Facebook saw this coming, and it’s probably part of the reason why it’s been so adamant on connecting the world with projects like Aquila, its internet-beaming drones, and Free Basics, a problematic program to bring internet access to underserved areas. It likely knows that it’s getting close to reaching market saturation in many Western countries, and that more than half of the world’s internet users already have Facebook, so it’s trying to find new ones.

It’s not likely that Facebook’s current advertising business model would work with these users—it currently only makes an average of about $7.60 per year on each non-Western user. The advertising markets in these countries just aren’t as developed as the ad-saturated societies in the West, and likely won’t be for many years. Facebook paid $19 billion to buy WhatsApp four years ago, and so far has done little to monetize the platform. It even dropped the $1 annual fee WhatsApp used to charge to use the service in 2016.

Facebook could experiment with putting more ads in WhatsApp, as it’s started doing with Messenger, but if there aren’t any local brands with cash to spend or international brands that aren’t willing to spend much to reach citizens in developing nations, given the relative income levels in emerging markets versus developed nations, it doesn’t really seem to matter how many more spaces for ads there are in WhatsApp or Facebook Lite.

But Facebook still has hundreds of millions of people that it can influence in ways other than advertising. Just because a free, ad-supported network works in the West doesn’t mean Facebook can’t explore other options elsewhere. If it were to roll out the WhatsApp payments system it’s testing in India more broadly, and charge a small fee for transactions, it could become the bank of the social web.

Given that so many people in so many countries are already using WhatsApp as a way to schedule appointments and services, it seems like a logical step to be able to pay for those through the app. Facebook could become one of the largest payments processors in the world overnight, if it wanted to. (For reference: PayPal, a leading internet payments company, generates around $4 billion per year in revenue.)

It’s not clear what would be holding Facebook back from rolling out something like this in nations where it knows groups of users have banking accounts—like India—but it may definitely be a far greater hurdle to bring something like this to a nation where many use WhatsApp but are unbanked, like Brazil or central Africa. And running a payments service like this would also have its own regulatory hurdles.

Perhaps there are other revenue models to explore. Facebook could offer users ad-free subscriptions to its services for a small monthly fee, or perhaps instead of generating roughly $20 from each global user off advertising, it could just offer users a service that doesn’t track them for around $20 per year. Even in the US, converting the average revenue of a user into a monthly feee would work out to be around $7 per month. That’s cheaper than a Netflix subscription.

Then again, even if Facebook were to lose its European and American users and all the advertising revenue that comes with them, it would still be generating around $4 billion per quarter through its current business model. That still would leave Facebook as a $16-billion-a-year company (which would see it sitting at around 170th on the Fortune 500 list), with many global opportunities to pursue other potentially large streams of revenue. Maybe that doesn’t sound so bad.