In August, a Chinese zoo became the laughing stock of the internet after it tried to pass off an unusually fluffy dog as an African lion. The zoo may never have had a real lion. Or perhaps it did at one point, and then decided to sell it to a taxidermist for some extra cash. That’s the subject of a recent expose by Southern Weekend (SW), an investigative newspaper: Surging demand for luxury home decor is encouraging zoos to kill their exhibits and sell their pelts to state-licensed taxidermy firms, reports SW, via China Dialogue.

Siberian tigers, for example, fetch around 3 million yuan ($490,000), earning the taxidermist up to 2.65 million yuan in profit. Even though there are only 360 Siberian tigers left on the planet, each step of this trade is technically legal.

Here’s how it works: The government lets zoos buy and sell wild animals at fixed prices. But only under what the report called “extraordinary circumstances” do zoos bear responsibility if an animal dies. That has given rise to the roaring trade in stuffed carcasses and luxury rugs made of the skins of rare and endangered species; at least 80% of animals that enter the taxidermy market come from zoos.

Stuffed animals have become particularly popular with businesspeople and government officials, thanks to the government’s ongoing crackdown on more conventional luxury gift-giving. Tigers, deer, monkeys and elephants are especially popular gifts because of their symbolic value. That might explain why there’s been a big uptick in “natural death and loss” of animals in Chinese zoos, as SW reports.

“Zoos are the most important part of the chain,” the head of one taxidermy firm told Southern Weekend. “The official price for a live tiger is sometimes less than 20,000 or 30,000 yuan. If you can have it die a ‘natural death,’ [zoos] can make a lot more money.”

None of this trade would be possible without the State Forestry Administration (SFA), which supervises China flora and fauna. It licenses the 600-plus taxidermy companies.

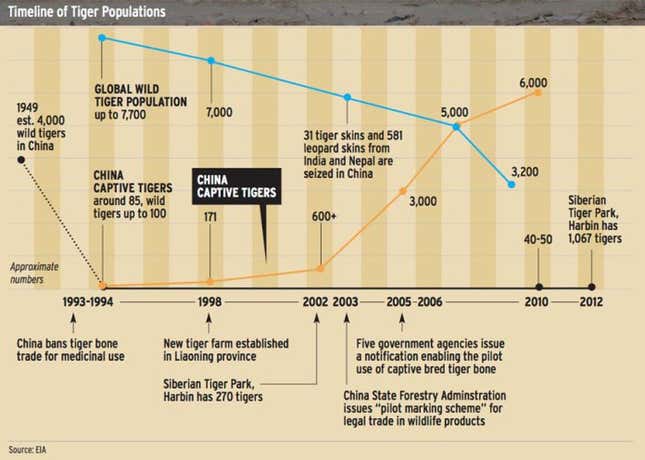

By setting up policies promoting the “breeding, domestication, and utilization” (pdf, p. 3) of certain rare animals for “conservation” purposes, the government agency encourages the practice, according to the non-profit Environmental Investigation Agency. In zoos and “tiger farms” authorized by the SFA, China’s captive tiger population is between 5,000 and 6,000, but its wild tiger population has fallen from 4,000 in the late 1940s to just 40 to 50 tigers today.

The presence of wild animal farms is ostensibly to discourage poaching, as Wang Weisheng, an SFA official, told the China Daily in 2012.

But if the dismal state of China’s tiger population is anything to go by (the chart below illustrates the decline in wild tigers and rise in captive tigers below), the booming legal trade has only exacerbated poaching. Many of the carcasses used for taxidermy come from China’s natural reserves, reported Deep, a publication of the China Association for Scientific Expeditions, in 2012.

Perhaps that’s because the SFA’s stance on dead animals is that they shouldn’t be “wasted”—implying that the taxidermy business, and not conserving animals, is the priority.

“As long as we don’t hurt our ecosystems, we must prioritize taxidermy to popularize science,” the SFA’s Wang told the China Daily.

Tang Jian, a fifth-generation taxidermist who maintains the natural history collection at Wuhan University, might beg to differ. “Beasts and birds of prey, beautiful birds—they’re making ornaments, not specimens,” Tang told SW.