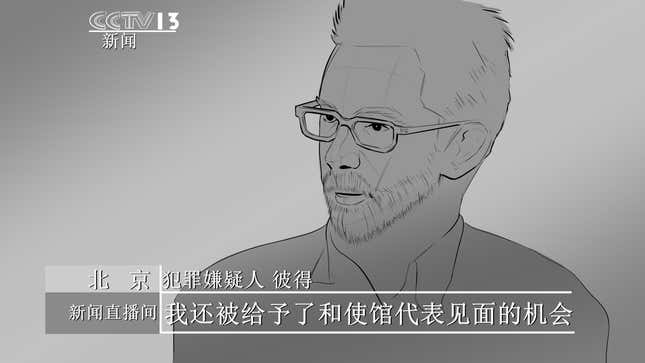

In January 2016, Swedish human rights worker Peter Dahlin, who disappeared on his way to an airport in Beijing, reappeared on China’s state broadcaster over two weeks later, and confessed to “endangering state security” by supporting the work of local activists. Even more shockingly, the then 35-year-old apologized for “hurting the feelings of the Chinese people,” a line straight out of the Chinese Communist Party’s playbook.

In recent years, amid a campaign by the Chinese government to stifle online activism, high-profile individuals—including lawyers, journalists, business executives, and rights activists—have been coerced into nationally broadcast confessions before trial and often even before a formal arrest. While the vast number of such confessions are forced from Chinese citizens, it has happened to foreign nationals too.

After his deportation from China following a 23-day detention, Dahlin for the first time described his ordeal in a 2016 interview with the New York Times (paywall). In a new report this week (April 10), Dahlin wrote his own account of how that confession was extracted. The following is excerpted from “Scripted and Staged,” published by human rights group Safeguard Defenders, which has documented 45 cases of forced televised confessions since 2013 in the report.

State Security Agent Zhang, who had taken to playing the “good cop” role while his colleague handled the “bad cop” act, arrived sometime after dinner time. “Have you had dinner yet?” he asked after entering my cell. He pulled up a chair next to my tiny bed; the two guards who would otherwise sit staring at me 24 hours a day left. These cozy “fireside chats”—I called them this because they reminded me of [former US president] Franklin Roosevelt’s World War II broadcasts, would happen every once in a while, and were a welcome break from the extreme boredom of solitary confinement, or the daily (or rather, nightly) intense five- to six-hour interrogations.

At this point, I’d spent some two or three weeks in a secret prison south of Beijing and had been accused of using foreign funding to subvert state power. The case was being handled by the Ministry of State Security. My girlfriend had been taken in the same raid, despite having no connection to my work, and was languishing while they decided on my case. A long list of colleagues or partners were taken either in the same operation or had been taken one by one over the preceding six months. Almost everyone was disappeared—not arrested—and placed into solitary confinement under what they call Residential Surveillance at a Designated Location, a new favourite new tool of suppression.

“I’ve just spent the whole day at court,” Agent Zhang told me. “You know I have pushed very hard for them to find a diplomatic solution… I have pushed for this hard, as I think it’s the best way to resolve the situation.” He told me he was going back again tomorrow to see the panel of “judges” who were deliberating my case and were deciding whether to prosecute me or not. There was a chance they could arrange a diplomatic solution on medical grounds. I knew full well that this is not how the legal procedure is supposed to work in China, but then again laws are rarely worth the paper they are written on there, and I had no reason to doubt him.

The initial accusations against me had all been dispelled. They wanted to end this. My medical condition—Addison’s disease which could be fatal—offered them a way out. They wouldn’t want a dead foreigner on their hands.

Every once in a while, Agent Zhang would visit me in my cell for these informal “fireside chats” instead of questioning me in the interrogation room. Often, a Nescafé would be offered, and he would bring a pack of cigarettes and I could smoke as much as I wanted. The heavy curtains would be opened for a bit of sunset light, or if it was night-time, the windows were opened for some fresh air. These were our “bonding” moments. Or rather, it was their way to create a sense of dependency in me for the “good cop” so that they could more easily persuade me to cooperate.

The previous night, I’d been woken at around three in the morning, hurried into the interrogation room opposite my cell, where for hours they had conducted a formal deposition. Agent Zhang was now saying he needed something more to convince the judges not to prosecute. My written self-criticisms had not been enough. “I want to record a video of you accepting responsibility and showing that you know what you did was wrong,” he said. The judges might be convinced by a video.

Up until this point they had spent a lot of time getting me to write self-criticisms. These were not about admitting any particular crime, and I never did commit a crime, but to admit to general wrongdoing. I was to put in writing, I now realized, that I had been wrong, that I had hurt China. Like Winston Smith, the protagonist in George Orwell’s novel, 1984, I was supposed to realize my wrongdoing, accept being reformed by the “helpful” State Security who had shown me the error of my ways, and to demonstrate that I actually believed it all. It wasn’t an easy task.

I assumed, although I was far from certain, that I would not be prosecuted, and that they were looking to find a way out. The media storm about my case had broken just a few days earlier—that much was made clear when they angrily asked about my relationship to the Reuters reporter Megha Rajagopalan who first broke my story, and who happened to be a friend of mine. Their anger about Michael Caster, my co-worker, who was handling advocacy and press on my behalf, was also clear. “He is spreading lies,” they would yell. “What he is doing is hurting you.” My casual remark that a phone call could fix all that did not go down well.

At that point, Agent Zhang stood up and said he had to arrange some things and would be back shortly. He told me he would inform the guards that I could have a shower. He also left me the pack of cigarettes and said he would instruct the guards to give me more Nescafé if I wanted. He told me to put on my own clothes after my shower, instead of what I wore everyday—grey sweatpants and sweater, with a fire-orange vest on top, all to make sure I felt like a criminal.

Not long after, maybe an hour or so later, he came back. He had brought his translator with him, which was rather comical because her English was no match for Agent Zhang’s fluent grasp of the language.

Agent Zhang handed me a piece of paper with handwriting on both sides. He told me it was a “summary” of what had been said before during my endless interrogations and last night’s deposition, but actually it was a list of questions and answers, and I was to be one of two “actors” playing out a scene. I quickly scanned the page and the true nature of this recording became clear. I had to say: “I have hurt the feelings of the Chinese people.” I became suspicious of the purpose of the recording, and that it might be for public use became clear—although no one admitted it—when later I was taken to the larger “meeting room” next to the interrogation room, and saw the CCTV “journalist” and cameraman.

But I still went along with it. I knew for sure that including that incredibly crass line also meant that the media frenzy would go into overdrive. Everything else they wanted me to say would be negated by that one line. I might as well say: “I’m being forced to do this against my will, and no one has any reason to believe any of this is true.”

Arguments followed. As always, they tried to subtly change my meaning or wording. During interrogations, we had had several shouting matches when both of us found our patience had run thin. The key issue was they insisted on calling lawyer Wang Quanzhang (王全璋) and other former partners “criminals,” even though none of them had been convicted of any crime. I refused point blank. “There is simply no way I will call them criminals,” I told them, even semantically it didn’t make sense. How can you be a criminal without a criminal conviction? They relented.

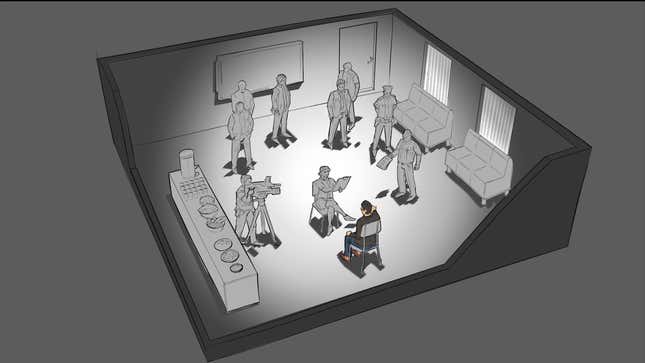

Agent Zhang then left again, saying that he’d be back soon. “Please study the answers and memorize them,” he told me. He returned with two guards in tow. They led me out of the cell across the narrow hallway to the “meeting room” where the recording was to be made. The room was packed. Agents Zhang and Liu (the “bad cop”), their supervisor, several young translators, the “journalist,” the cameraman, the officer who always handled taking notes, as well as several guards were all there. A small chair was reserved for me along the wall. Opposite, but outside of view from the camera, sat the female “journalist,” holding a piece of paper with the questions State Security had instructed her to read. She knew as well as me she was to be an actor, reading the lines as instructed by “director” Agent Zhang.

The “journalist” introduced herself. Confident. Fashionably dressed. Pretty. In her late 30s or early 40s. I was offered another cup of bland Nescafé. Behind us, one of the agents was holding a handheld camera. They discussed amongst themselves for a while, maybe even 30 minutes, taking the paper from me and making small changes.

“Ok, let’s go,” the “bad cop” finally said.

We ran through the seven or eight questions. A few retakes. Sit straighter they say. Speak slower here. Change this here. Guidance. In between takes, the main “director” and “screenwriter” Agent Zhang discussed changes with the “bad cop” and their superior, a sleek woman, maybe in her early 50s. Additional changes and re-takes followed. Once in a while, after scribbling changes, they handed me the paper so I could learn my new “lines.” Once, I placed it down on the floor beside me before shooting resumed, but Agent Zhang spotted what I was trying to do and nabbed it, making sure it wouldn’t be in shot.

Most questions went well. I stumbled four times on the only line I really wanted to say: “I have hurt the feelings of the Chinese people.” After the fourth take the “journalist” leant in and said: “You really don’t want to say this line do you?” She couldn’t be more wrong. I nailed it on the fifth.

I was led out, back to my cell, but told to keep my own clothes on. They came back and fetched me two more times to record some minor additions here and there. I was given updated versions of the paper to show me what I needed to say. It was all done by 11. Agent Zhang seemed pleased. I was too.

Was it embarrassing? Were you hurt? Do you regret it? These are common questions from friends and journalists. Or, why did you do it? It’s hard to answer these questions because when you do it makes it sound like you’re trying to rationalize why you did it. For me, however, it was never really an issue. I had selfish reasons, such as I wanted to speed up my release, and the media frenzy I knew would come after being forced to say, “I have hurt the feelings of the Chinese people” would help with that. Every day I was being held mattered in terms of my medical condition. Other motives were nobler. I was repeatedly told that my girlfriend would only be released once my case had been dealt with, either by some form of release or being moved into pre-trial detention. They kept reminding me of this. Once, they showed me a photocopy of a drawing she had been allowed to make. It was devastating. That and when they told me later she was being freed, were the only two times I almost cracked, but in the end, I managed to keep my tears in.

Because I didn’t have to call Wang Quanzhang and some other colleagues criminals meant I didn’t really say anything of substance in that confession, and because I didn’t have to denounce others means the only thing that’s left is the embarrassment of it all, a small price to pay for my girlfriend’s and my own freedom. I also wanted badly to continue my rights work, and that was more important than being some kind of martyr. Unfortunately, what I didn’t know at the time, was that the attack on my organization had been so wide-ranging that the NGO that I had run for so many years had to be dismantled.

Unlike many other victims of forced televised confessions, I’ve always operated behind the scenes. Few people, even my close friends, were aware of what I did, so I had no public reputation that could be destroyed. Still, it’s embarrassing to be paraded on national television in front of hundreds of millions of viewers, and to this day, more or less every week, my name pops up in the news, and it’s usually connected to that forced televised confession.