A woman is challenging Japan’s resistance to immigrants by helping foreigners find work

They stack shelves in Japan’s ubiquitous convenience stores, work on construction sites, even clean up radioactive debris at Fukushima—but officially, the blue-collar workers doing this work do not exist.

They stack shelves in Japan’s ubiquitous convenience stores, work on construction sites, even clean up radioactive debris at Fukushima—but officially, the blue-collar workers doing this work do not exist.

The Japanese government does not officially allow work visas for people to do low-skilled, manual jobs. Such workers instead enter Japan as foreign students who work on the side, or as “technical intern trainees” who are supposed to only stay temporarily and no more than five years. It’s a workaround that keeps the government from having to admit that it is, in fact, opening up the country—many in Japan remain deeply apprehensive about immigration even as Japan struggles with a severe labor shortage. But it’s also a workaround that leaves thousands of workers vulnerable to exploitation by employers and the brokers who bring them over.

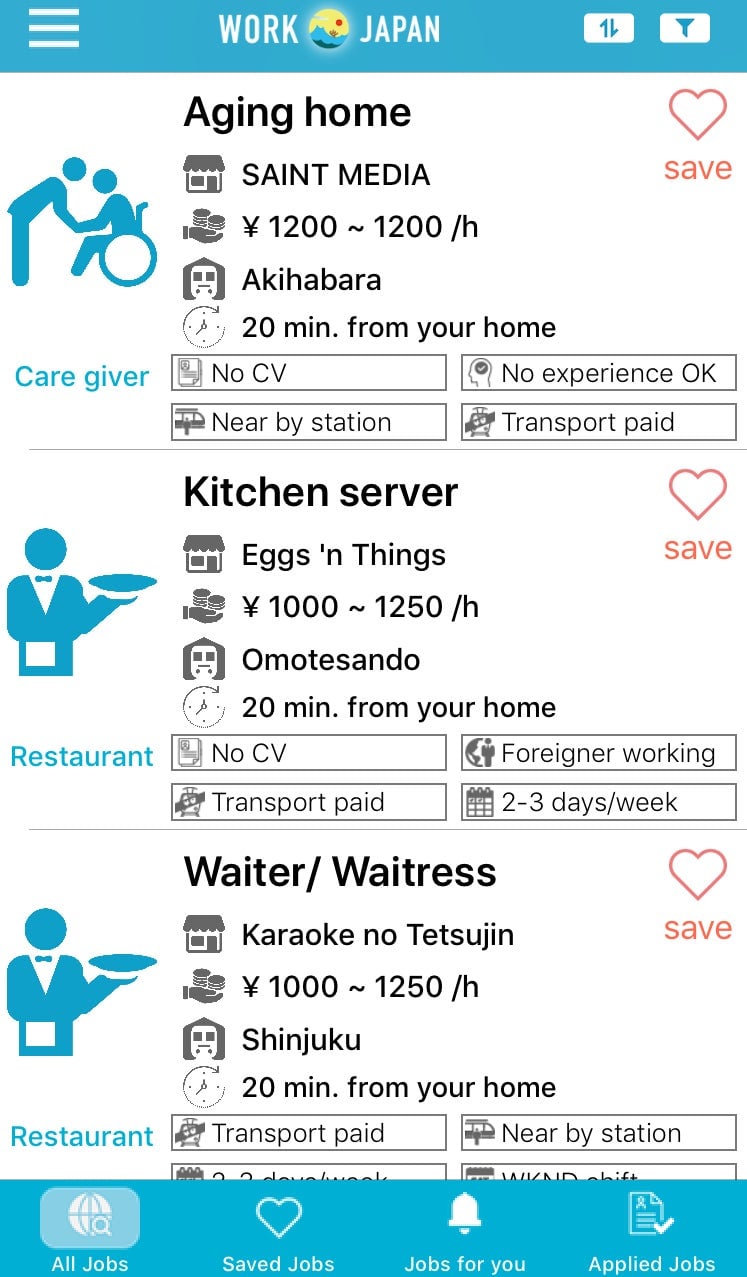

Misa Matsuzaki, a 48-year-old entrepreneur, is trying to change that with an idea that sounds simple, but has yet not been tested in Japan—creating an app that directly connects employers with those blue-collar job seekers who are already in Japan. Work Japan, she explained, is one way to alleviate the problem of exploitation by creating a more transparent platform for workers to find jobs matching their interests, skills, and location, cutting out exploitative and expensive middlemen in the process.

Matsuzaki got the idea after attending a conference in Bengaluru in 2016, where she met the founder of Work India, an app that aims “to completely remove the significant information asymmetry that exists between the employers and employees” in the manual-labor segment.

“This is what I want for Japan,” Matsuzaki thought at the time. She got to work hiring Indian software engineers to build Work Japan, which launched in November for Android and December for iOS. It now has about 2,000 job postings, a drop in the bucket compared to Japanese recruitment website behemoth Recruit or manual-labor-focused Town Work (link in Japanese).

Impossible to ignore

But Matsuzaki also sees a lucrative business opportunity in starting Work Japan. Despite the government’s reticence to implement a proper visa regime governing the import of manual laborers, Matsuzaki said their numbers have still exploded in Japan, doubling in the past five years. Her hope is for Japan to move closer to being an economy that is open to immigration like Singapore or Hong Kong—both of which still suffer labor shortages—where many foreign laborers work in construction, restaurants, and in people’s homes as domestic helpers.

Of the over 2 million foreigners living in Japan, some 1.3 million are workers, a 17% increase from the previous year, and about 258,000 of them are trainees (paywall). Most of these new arrivals come from China, though there are also sharply increasing numbers coming from Vietnam and Nepal. The app is currently available in languages including Japanese, Chinese, Vietnamese, Burmese, and Portuguese, the last aimed at Japanese Brazilian workers.

The entrepreneur has spent much of her career shaking things up in Japan, becoming the youngest woman ever to take a company public in Japan in 2004, as the chief executive of Agasta, a company that exported Japan’s used cars. After leaving the company in 2009, she partnered with a Singaporean businessman to launch PeopleWorldwide in Japan, a recruiting agency for bringing in workers as trainees or under other visas. She credits her openness to foreigners to her years spent attending primary school in South Africa, where her father worked for a Japanese trading house, such that her “perception of foreigners is very different to the usual Japanese [person’s].”

“I always wanted to be the connection between Japan and outside,” said Matsuzaki. “My first business was exporting cars. Now I’m bringing in people and structuring a better life for them.”

“The government estimates that by 2025 we will have 6 million laborers disappearing from the workforce. Who is going to cover their work?” said Matsuzaki.

‘Utilizing foreign human resources’

So far Japan has seen mostly small steps to expand the employment of some foreigners, many from the Philippines, in the elder-care sector. In 2016, Japan lifted a ban on foreigners working as maids and last year allowed 25 Filipino women to work in homemaking in special zones in Tokyo, Osaka, and Kanagawa prefecture. This may help more Japanese women stay in the workforce, but may not help employers seeking manual laborers. “In Japan, having a maid is a super, super luxurious thing,” Matsuzaki said.

The latest figures released by the Japanese government showed that the population declined in 2017 for the seventh consecutive year, with people over 65 making up 28% of the population. Even so, it is largely politics that stymies any decisive action on the part of policymakers, Matsuzaki explained.

“Here in Japan the reason we don’t give this type of [worker] visa is because this is an island which is homogenous… Everyone says we are not ready for opening up,” she said. “I can feel that politicians aren’t negative about the topic, but they don’t want to touch it. If they touch it they might lose votes.”

Prime minister Shinzo Abe, who has staked much of his political capital on revitalizing Japan’s economy, has himself shied away from using the term “immigration.” In 2014, he clarified that his policy of “utilizing foreign human resources” to tackle Japan’s demographic timebomb was not the same as having an “immigration policy,” wrote Eriko Suzuki, an education professor at Kokushikan University in Tokyo. During last year’s general election, Abe’s opponent Yuriko Koike, the maverick female governor of Tokyo, came out against giving foreigners in Japan the right to vote in local elections, despite her pledge to improve diversity in the country.

Money talks

Matsuzaki thinks it’s only a matter of time before the government has to listen to the bosses of factories, restaurants, and convenience stores in Japan and face the music when it comes to the necessity of immigration. The country is investing heavily in technology such as unmanned convenience stores and replacing caregivers at elderly homes with robots, but it’s unlikely that artificial intelligence can come close to replacing the shortfall in labor.

“Top management [in Japan] read the newspapers, and they are really desperate. They know that they have to do something, the government has to do something, otherwise they’ll have to shut down their stores, or be sued by workers for making them work too long,” she said, referring to the growing outrage in Japan over karoshi, or death by overwork.

The job-to-applicant ratio in Japan is at a historic high of 1.58, or 158 jobs for every 100 applicants, according to the latest data released in March. For manual jobs like security guards, Matsuzaki estimates that there are as many as seven vacancies for every applicant. So desperate are some convenience stores, she said, that they’re “even using dark-skinned persons as store managers.”

It’s a significant development in an insular country like Japan that makes Matsuzaki “not optimistic, but not negative” about her business, and Japan’s future. “I can feel that in the business sector there are people like myself fighting or taking this very seriously,” she said. “We have to change.”