The US, UK, and France have launched a barrage of 105 cruise missiles against the Syrian state, designed to target an alleged chemical-weapons program used by strongman Bashar al-Assad against insurgents.

Why the strike?

On April 7, Syrian forces allegedly used chemical weapons, including chlorine gas and an unspecified nerve gas, to kill dozens of civilians and injure hundreds more, according to Western intelligence agencies and on the ground observers. President Barack Obama was famously criticized for looking past previous chemical weapons use by Assad for fear of being dragged further into the conflict. Trump has not been so cautious, launching 58 cruise missiles against a Syrian airport in 2017 after a previous chemical attack by the regime.

What have the strikes done?

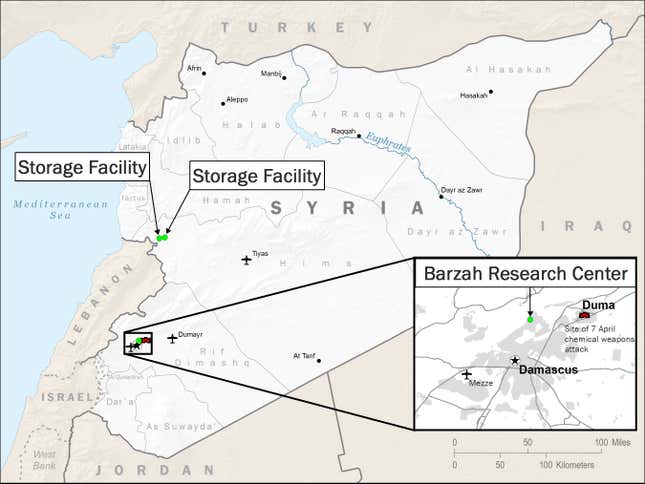

US and French Navy ships and submarines fired cruise missiles from the Mediterranean Sea and the Persian Gulf; US, UK, and French military aircraft did the same while flying a safe distance outside Syria. The 105 missiles fired hit buildings in Damascus believed to be associated with chemical weapons production, a nearby military command post, and a chemical weapons storage facility west of the city of Homs. “Obviously, the Assad regime did not get the message last year,” US defense secretary James Mattis told reporters. “This time we have struck harder.”

What’s a cruise missile?

A cruise missile is essentially a flying jet engine with a 1,000 lbs (454 kg) bomb attached to it. The Tomahawk cruise missile, by far the most prevalent, is manufactured by defense contractor Raytheon. It approaches its target flying at nearly 600 mph (900 kph) before delivering its explosive warhead.

While the Tomahawk is in its fourth decade as the premier US long-distance attack missile, this strike marks the first use of a new air-launched cruise missile called JASSM (Joint Air to Surface Standoff Missile), which carries a 2,000 lb (900 kg) bomb.

How destructive are they?

Check out this dramatic test footage broadcast on TLC:

Or this recent video of what it’s like to be in an airstrike. Whether they are effective at deterring bad activity is another question. During the April 2017 strike on a Syrian airfield, several planes were destroyed, along with hangars, and the runway was damaged. Still, it was in use the next day.

Yet buildings are in a sense easier to knock of commission than a runway. Still, it’s clear these strikes were carefully targeted to send maximum message with minimum destructiveness. Striking at night limited the presence of people in the buildings, and efforts to avoid escalating a conflict with Russia by “deconflicting”—essentially warning them of the attack—likely resulted in some warning to Syrian forces as well.

We’ll need to wait for satellite photography and on-the-ground reports to determine the extent of the destruction.

Did Russia or Syria shoot down any cruise missiles?

Syrian state news is saying the attack failed, and Russia says it shot down 71 missiles using air defenses. It’s unlikely that the attack failed—indeed, observers on the ground are reporting at least some successful hits—but it’s possible that a few of the missiles were struck by air defenses like the Russian S-400 system. It’s always good to take claims of missile defense skeptically; but cruise missiles travel much slower than ballistic missiles and could have been shot from the sky.

With so many missiles incoming, it’s unlikely the defenses slowed the assault. The DOD says it hit every target, and that only 40 interceptors were launched by Syria, many after US missiles already struck. Military officials claimed that some of the Syrian interceptors were un-guided and posed a risk to civilians when they inevitably returned to earth.

Still, purchasers of the S-400 system like China and India will be pleased to note that the US and its partners chose not to fly piloted aircraft within their range.

What’s next?

Nothing? The Trump administration is portraying this as a one-time strike to deter Assad from using chemical weapons, and degrade his ability to do so in the future. Military officials say what’s next depends upon what Assad does. One thing is for sure: the US has no obvious strategy in Syria.

Russia has reacted with outrage; their diplomats strangely described the attack as an insult to their leader, Vladimir Putin. Russia has promised some military reaction, but it is unclear what form it will take. The Syrian civil war will continue unabated.

The operative question—will Assad stop using chemical weapons?—is perhaps the hardest to read. Clearly he will think twice before launching a major chemical attack, but perhaps the lesson he will take away is that smaller chemical attacks, used between the two airstrikes, will be ignored by international powers—or that he should simply use barrel bombs and cluster munitions to kill civilians, like US allies.