Reuters published an investigative series last week on Americans abandoning adopted children and looking online to find other families to take them. The new guardians have had little screening; tales of abuse and neglect abound.

Failed adoptions are, sadly, common. Somewhere between 10 to 25% of domestic adoptions fail. No statistics are available for international adoptions, but consider Reuters’ own findings: In the 261 children trying to be “re-homed,” 70% were international adoptees; many were described as having attachment disorders.

There’s more bad news: Recent trends in international adoptions suggest that a higher share will fail. And that’s despite a fall in US adoptions from overseas. Here’s why:

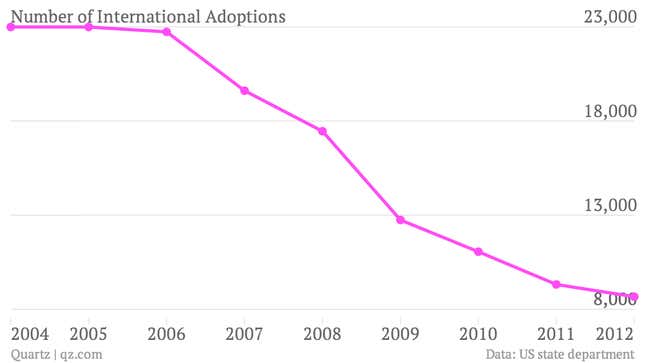

These days, countries that have traditionally been a large source of children, like China and Guatemala, allow fewer adoptions or in Russia’s none at all. The figure below shows the number of international adoptions from the US State Department.

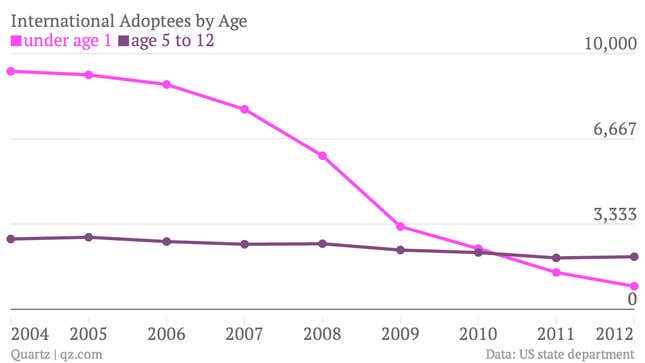

But the fall in adoptions masks an interesting trend: The decline is limited to young babies. The number of international adoptees between ages 5 to 12 fell only slightly since 2004, while the number of children under age 1 fell 90%. Older children now make up a much larger share of international adoptees. The figure below plots the number of adoptees for the two age groups.

In 2004, children under 1 accounted for more than 40% of international adoptions, now it’s just 10%. Meanwhile, children 5 to 12 used to be just 12% of adoptees, now it’s 24%.

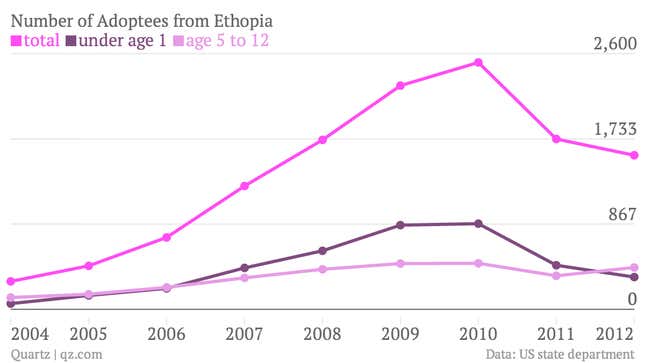

The reason boils down to laws of supply and demand: Older children are abundant. And when countries like China and Ethiopia revisit their adoption policy, they seem to restrict the number of young adoptees—but they still want to place older kids. The figure below plots the remarkable growth and then contraction of Ethiopian adoptions in America. Starting in 2011, the Ethiopian government started to restrict international adoptions and the number of young babies adopted fell.

This is significant because older adoptees tend to have a harder time adjusting to their new families. The older the child is when she or he’s adopted, the more likely she or he will have an attachment disorder. Attachment disorder impairs the ability to connect with adoptive parents and form relationships. Studies show that connecting with a regular, loving, and attentive caregiver during your first few years is what enables you to form attachments for the rest of your lifetime.

Even before the Reuters series, there were plenty of anecdotal stories of failed adoptions. Writer and columnist Joyce Maynard wrote of her decision to adopt two Ethiopian sisters—and then find them another home when it didn’t work out. There is also the infamous Tennessee woman who adopted a 7-year-old from Russia. When she couldn’t cope with his behavioral problems, she sent him back to Russia alone. That incident is often referenced as the reason Russia no longer allows its children to be adopted by Americans—though politics certainly played a role, too.

The data brought to life in these heartbreaking stories suggest we may want to rethink policy around international adoption. Certainly, the process has the potential to improve welfare both at home and abroad by matching needy children with loving families eager to parent. And many older children experience successful adoptions, especially children who did not spend their infancy in an institution.

But the changing profile of international adoption should be tackled head on: with more resources, better screening of both parties, awareness and education of adoptive parents. Otherwise the world’s most vulnerable children will only find more hardship in their adoptive country.