It has a better track record than Nouriel Roubini, Paul Krugman, and many—if not most—high-profile economic forecasters. The shape of the yield curve—that is, the arc of US government bond yields across the spectrum of maturities—has a good record of predicting recessions in America since the 1960s.

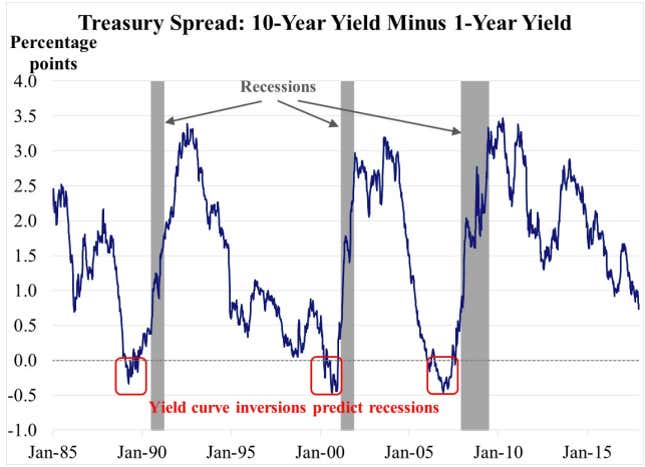

The figure below, taken from a recent presentation by the president the St. Louis Fed, illustrates how each of the past three recessions was preceded by an inverted yield curve, with the 10-year bond yield dropping below the one-year yield:

Normally, long-term bonds offer higher yields than short term bonds because they are riskier—a lot more can happen over 10 years than over one year. When this relationship reverses itself, investors worry. Indeed, since the 1960s, there has only been one false positive for this indicator. Now, almost 10 years into a recovery, investors are closely watching the shape of the yield curve.

Why investors are worried

Although the yield curve has not inverted yet, it has flattened recently. This is primarily down to the Fed pushing up short-term rates while long-term yields have barely budged. The flattening could herald an inversion in the near future.

Short-term interest rates are influenced by Fed policy and the demand for short-term capital. But nobody knows for certain what determines long-term interest rates, because they are a function of many overlapping factors that are hard to isolate.

One of the simplest factors is what economists call the expectations hypothesis. It assumes that long-term rates reflect investor expectations of future short-term interest rates. If this is what’s behind the flatter yield curve now, we should be worried. Low long-term rates could mean bond investors think a recession is coming, and when it does the Fed will cut short-term rates.

Another factor informing the shape of the curve is inflation expectations. Investors often hold long-term bonds for many years, or even decades. In that time, inflation can eat away at interest payments, especially if inflation is higher than expected. Long-term yields tend to be higher than short-term yields to compensate investors for inflation risk. Stubbornly low long yields could be an ominous sign if it reflects expectations for low inflation due to a weak economy.

Why this time may be different

Long-term rates also include a risk premium. Long-term bonds are risky, they are harder to sell than short-term bonds, and their prices are more volatile. Investors usually want to be compensated for taking on these extra risks, demanding higher yields as a result. Low long-term yields today could mean there’s a lower risk premium, meaning that investors expect exceptionally smooth sailing ahead.

A research paper by economists Menzie Chinn and Kavan Kucko argues that the yield curve has not been able to predict recessions in other countries (pdf), especially after big, structural changes that alter how debt markets function, like the adoption of the euro.

Was the Great Recession in the US a structural change? The IMF recently fretted fretted about the shape of the US yield curve, but noted that it may be flatter because after the 2008 financial crisis central banks around the world bought huge amounts of long-term bonds to steady their teetering economies and volatile financial markets. Bond investors may think this will happen again if there’s another recession. A ready and willing buyer of long-term bonds means less risk in the market, lower risk premiums, and lower long-term yields.

An article in Bloomberg speculates that if long-term yields don’t start to increase, the Fed may rethink future rate hikes to maintain the steepness in the yield curve. But if the flattening curve signals a recession, it is not clear the Fed can do much to stop it. An inverted curve does not cause a recession, but—usually—signals that investors anticipate economic weaknesses associated with a pending recession. Keeping interest rates low cannot always fix those weaknesses or alter expectations. What’s more, we can’t be sure that an inverted curve still means what it once did.