The good news is that mobile phones and the internet are bringing millions of people into the formal financial system, meaning they have bank accounts or a mobile money provider for the first time. This is important because financial inclusion is crucial in helping people save money for an emergency, get loans to start businesses, and escape poverty. The bad news, however, is that the financial-inclusion gap between men and women in developing economies hasn’t improved in the past six years.

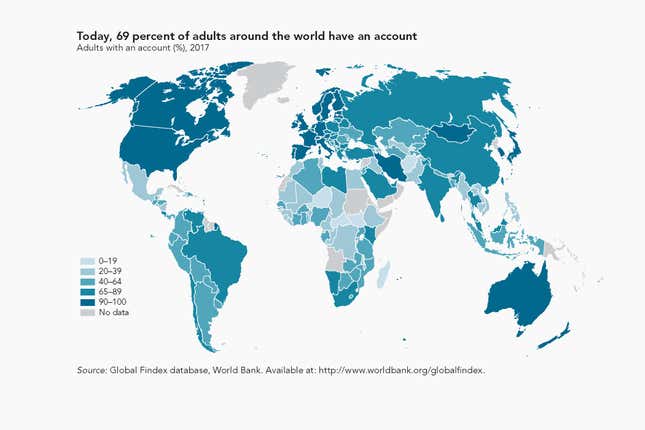

Some 3.8 billion people around the world, or 69% of all adults, have a bank account or mobile money provider as of last year, which is up from 62% in 2014, according to the World Bank’s Global Findex database. About 1.2 billion adults have obtained some sort of formal financial account since 2011, when the rate of financial inclusion was just 51%. Still, there are 1.7 billion people around the world who remain outside of the formal financial system. The World Bank notes that two-thirds of these people have a mobile phone, providing a potential platform to open an account in the future.

In developing countries, the gap in financial inclusion between men and women has stalled at nine percentage points. Not every emerging market has this disparity—men and women are equally likely to have an account in Cambodia, Indonesia, Myanmar, and Vietnam, for instance. Even so, making sure women have equal access to financial services can change lives, said Melinda Gates, co-chair of the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, which helped fund the index.

When governments deposit social welfare payments directly into women’s digital bank accounts, for example, it empowers their decision-making at home. Research suggests that when women have more financial autonomy, spending in the home tends to be reprioritized, such as in the interest of children, and can also boost labor force participation among women.

The gender gap is particularly wide in the Middle East and North Africa: Only 35% of women, compared with 52% of men, have a financial account of some sort, which the World Bank says is the widest disparity of any region. As many as 20 million unbanked adults in this region send or receive money domestically using cash or an over-the-counter service. There could be room for rapid improvement, because mobile devices are widespread—among the unbanked, 86% of men and 75% percent of women have a mobile phone.

The size of the gap in financial inclusion between rich and poor also isn’t budging. In high-income economies, 94% of adults have an account compared with 63% in developing economies. The gap between rich and poor adults within economies has also stalled, at about 13 percentage points in recent studies.

There are ways to boost financial inclusion. Digital public pension payments could reduce the number of unbanked adults in Europe and Central Asia by up to 20 million. By making wage payments electronically, businesses in Latin America and the Caribbean could expand account ownership to as many as 30 million unbanked people. Millions in the East Asia and Pacific region still pay utility bills in cash, even though they have mobile phones. And “opportunities abound” in Sub-Saharan Africa, the World Bank says, where mobile money is already widespread but some 95 million unbanked people still receive cash payments for agricultural products.

South Asia experienced a large improvement in financial inclusion in the past three years, rising 23 percentage points to 70%. This is mostly down to India, where the World Bank attributes the gains to the government’s biometric ID system. While the system has been criticized, particularly due to concerns about data protection, its uptake has brought a lot of women and poorer adults into India’s formal financial sector.

That being said, it matters whether people actually use these accounts rather than just own them. According to the World Bank, about a fifth of account owners hadn’t made a deposit or a withdrawal in the past year, with particularly high rates of inactivity in South Asia.