How Congress helped force the Fed to postpone the taper

There’s one big clue in the Federal Reserve’s monetary policy statement today explaining why it chose not to taper (or abate or ebb or dwindle) its bond-buying stimulus program:

There’s one big clue in the Federal Reserve’s monetary policy statement today explaining why it chose not to taper (or abate or ebb or dwindle) its bond-buying stimulus program:

Taking into account the extent of federal fiscal retrenchment, the Committee sees the improvement in economic activity and labor market conditions since it began its asset purchase program a year ago as consistent with growing underlying strength in the broader economy. However, the Committee decided to await more evidence that progress will be sustained before adjusting the pace of its purchases.

In English, that means: “The government has been cutting deficits really fast, hurting the economy and killing jobs. Despite all that, things are getting slightly better, but we want to make sure they keep getting better before we taper.”

To be sure, part of the concern was fast-rising rates prompted by the Fed’s communications snafus this summer, when it hinted that a taper was imminent. Markets priced in a taper, pushing up interest rates and slowing down credit growth.

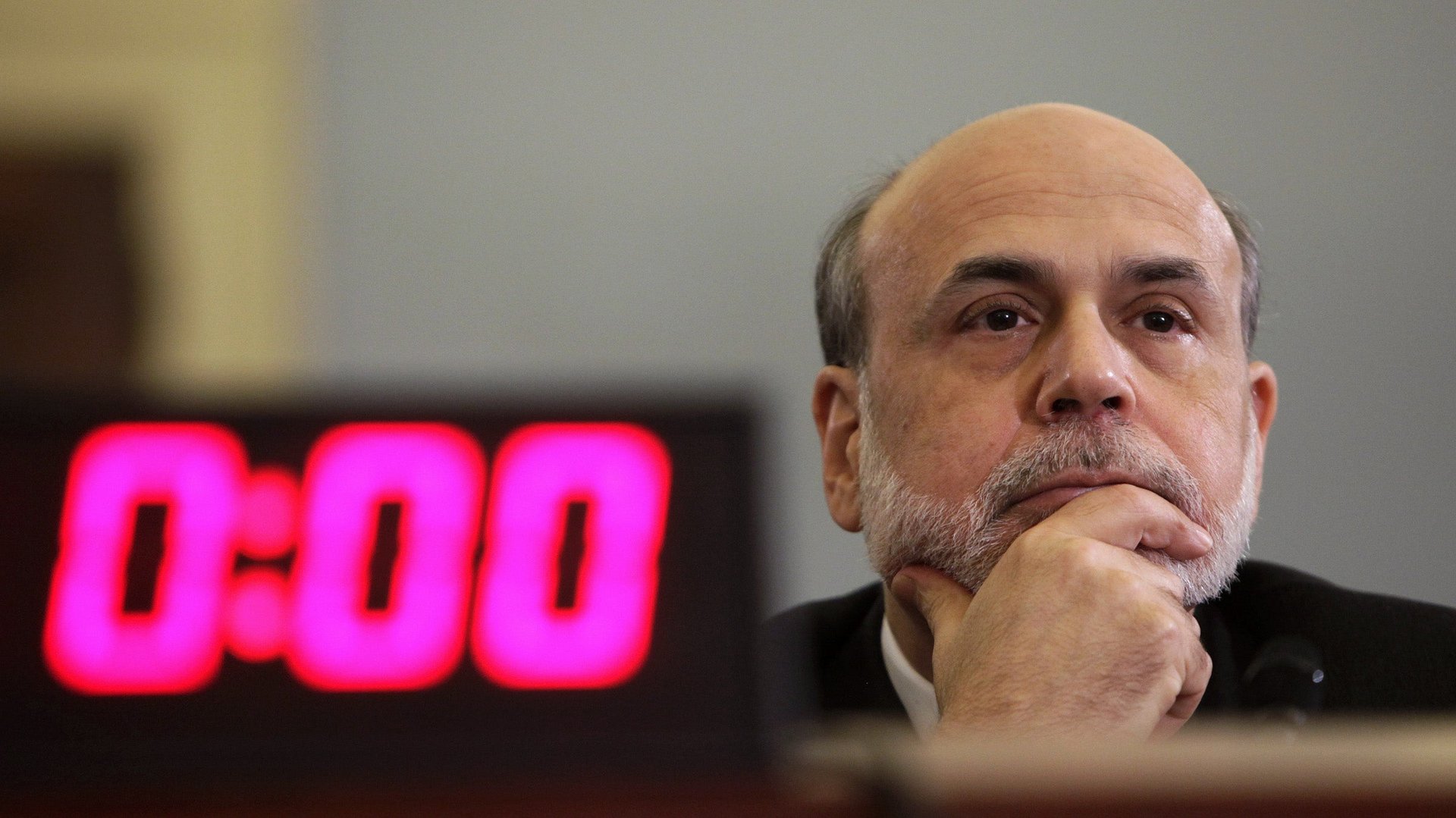

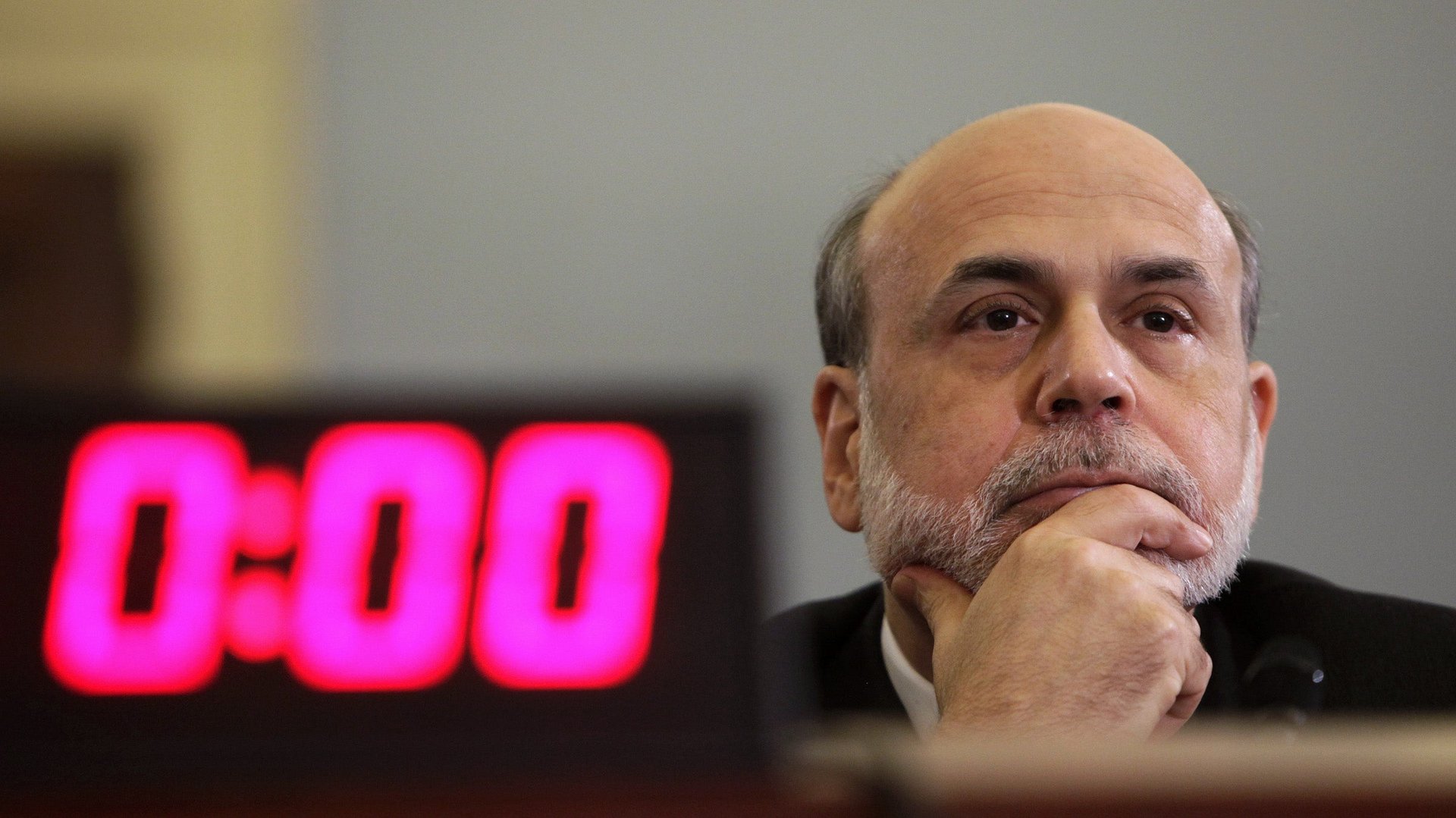

But Bernanke highlighted fiscal policy in his testimony before Congress this summer: “Risks remain that tight federal fiscal policy will restrain economic growth over the next few quarters by more than we currently expect, or that the debate concerning other fiscal policy issues, such as the status of the debt ceiling, will evolve in a way that could hamper the recovery.” At his monetary press conference today, he noted that deficit reduction will have cost perhaps a percentage point of growth and hundreds of thousands of jobs in 2013.

Or, as economist Justin Wolfers put it, “Monetary policy would look very different if only Congress stopped trying to choke off the recovery.”

Part of that evidence the Fed will be looking for is the results of the next month of fiscal debates. Will Congress and the president agree on a fiscal deal that eases near-term spending cuts while improving the long-term debt picture? Will a government shutdown or debt limit brinksmanship roil markets?

The politicians in Congress most eager to see the Federal Reserve remove its relatively novel supports for the economy are also those most eager to continue quickly cutting the US deficit. They may need to pick one or the other.