China’s nuclear path may offer a lesson to Trump on how to deal with North Korea

For the first time, a sitting US president has agreed to meet with the autocratic leader of a longtime communist adversary that owns nuclear technology.

For the first time, a sitting US president has agreed to meet with the autocratic leader of a longtime communist adversary that owns nuclear technology.

Are we talking about the potential summit between Donald Trump and North Korea’s Kim Jong-un in June? Yes. And it could just as easily be a reference to Richard Nixon’s historic visit to China in 1972.

North Korea and South Korea held top-level talks at their border today (April 27), vowing to end “all hostile acts” and work this year toward establishing a lasting peace. It’s a step that could continue to pave the way for the first-ever summit between an incumbent US president and a North Korean leader, which Trump unexpectedly agreed to last month.

Ahead of the two Koreas summit, the North had announced it will suspend all nuclear and missiles tests, and make economic development the nation’s first priority. While no one is sure what’s about to happen next, it’s worth looking at 1970s China for inspiration. Back then, China turned itself from a rogue nuclear power to an accepted member of the international community, while opening up its economy to the world.

History may not repeat itself. Pyongyang has a track record of halting its nuclear activities to get concessions, only to start them again later. In addition, the rogue regime is by no measure as geopolitically important as Beijing was even back then, so the international community is much more likely to seek an end to its nuclear program than to accept its nuclear status.

Still, the history of China’s nuclear program may offer some lessons to Trump on how to deal with Kim.

Mao counters the American “paper tiger”

On the eve of North Korea’s first-ever nuclear test in 2006, Pyongyang cited Washington’s threat to attack the country with nuclear weapons as a reason to develop its own nuclear arsenal—not unlike Beijing’s stance in the 1950s.

China launched its program during one of its most difficult periods. Not long after entering the Korean War to help the North fight against the US and South Korea, China went straight into another conflict in the Taiwan Strait. In 1953, the US pulled its ships out of the strait, allowing the Nationalist government—which fled the Chinese mainland after a defeat in the civil war—to deploy thousands of troops to the islands there the following year. The Communist government quickly responded by shelling two islands the Nationalists occupied, with the determination to “liberate Taiwan” (pdf). In 1955, the US threatened a nuclear strike on China to end the crisis. That same year, China decided to develop its own nuclear weapons and ballistic missiles.

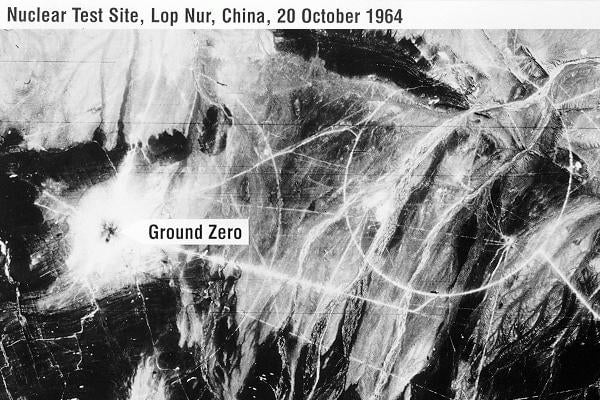

In October 1964, China detonated its first atomic bomb at the Lop Nor test site in the far western region of Xinjiang, raising concerns in the US and also the Soviet Union, which had fallen out with its communist ally. China followed up with its first hydrogen bomb test in 1967 and its first satellite launch in 1970, completing the “two bombs and one satellite campaign” initiated by Mao Zedong.

Mao told an American journalist in 1946—just a year after the US bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki—that the atomic bomb is just a “paper tiger which the US reactionaries use to scare people. It looks terrible, but in fact it isn’t.” But later, when China decided to develop nuclear weapons, he said, ”[Imperialism] looks down upon us, because we don’t have atomic bombs, but only grenades.” In a 1957 speech, Mao is said to have boasted that he had no fear of how many people would die in a nuclear war:

I’m not afraid of nuclear war. There are 2.7 billion people in the world; it doesn’t matter if some are killed. China has a population of 600 million; even if half of them are killed, there are still 300 million people left. I’m not afraid of anyone.

Prior to China’s first nuclear test, US president John F. Kennedy ordered his administration to make contingency plans including a preventive strike on China’s nuclear facilities. “But after looking at all their options long and hard, the analysts conceded that success would be fleeting. Beijing would rebuild its weapons infrastructure within a matter of a few years,” wrote Bennett Ramberg, a policy analyst in the George H.W. Bush administration, in a 2012 article.

China never became the nuclear nightmare many feared. ”Rather, by assuring the country’s security, the bomb gave the country enough confidence to think of the United States as an equal rather than an adversary,” Ramberg noted.

Sports diplomacy bounces to a state visit

After decades of frostiness, China and the US started to engage with “ping-pong diplomacy” in the early 1970s. In April 1971, the US team visited China for a 10-day tour, becoming the first group of Americans to set foot on the mainland since 1949. Though pampered with banquets, the US players were also treated to a taste of Cold War tension—during one stopover, a “Welcome American Team” banner was hung over a wall painted with the words “Down With the Yankee Oppressors and Their Running Dogs,” team president Graham Steenhoven noticed.

Shortly after this historic trip, the US lifted its travel bans and trade embargoes on China, and US national security advisor Henry Kissinger visited Beijing on a secret diplomatic mission in July 1971. That finally paved the way for Richard Nixon’s 1972 visit to China, the first by a sitting US president.

In 1971, the UN recognized the Communist government in Beijing as the only lawful representative of China, awarding it the permanent Security Council seat that had been held by the Nationalist regime in Taiwan. In 1979, the US and China established formal diplomatic relations on the basis of a “One China” policy.

Writing for the Diplomat (paywall) in August, Yevgen Sautin, a China expert at Cambridge University, pointed to a State Department study from the Kennedy administration to explain that the US decided to live with a nuclear China because its arsenal wouldn’t alter the military balance in Asia. The threat was resolved by US reassurances to its allies, just as the report had recommended.

Indeed, even though in the wake of China’s first nuclear test Japan expressed a strong desire to develop its own bomb, the [Lyndon B.] Johnson administration was able to provide security reassurances combined with diplomatic pressure to dissuade Tokyo from going down the nuclear path. In the subsequent years, the United States applied similar pressure to block Taiwan and South Korea from going forward with their own nuclear weapons programs.

“If China’s nuclear program did not pose a serious threat to the United States in the 1960s, then there is even less reason to fear North Korea’s today,” Sautin said.

Reform and opening up

During a key meeting of his ruling Workers’ Party last week, Kim announced that North Korea has achieved a “great victory” in his signature byungjin or “parallel advance” policy. That means the country no longer needs to test nuclear weapons or missiles, Kim said, and can shift its focus onto economic growth.

If Kim is serious about building North Korea’s economy, he might want to look to Deng Xiaoping as an example. The Chinese leader ushered a series of market-oriented reforms starting from 1978, lifting his country out of industrial backwardness and onto the global stage.

The question about whether Kim can become a Deng for his country was first floated when he took power in 2011 after his father’s death. The North Korean economy does appear to be improving, thanks to reforms in areas from agriculture to construction (paywall). It remains unclear to what extent Kim would like to follow the Chinese model, which is essentially an authoritarian capitalism.

“Whether Kim Jong-un will become the Deng Xiaoping of North Korea will depend on whether the international community, including the United States and South Korea, can provide security guarantees and opportunities for economic development so that it will denuclearize,” Cheong Seong-chang, a senior North Korea expert at the Sejong Institute, a research think tank in South Korea, told the New York Times (paywall).

“If North Korea somehow became a normal country and became an economically open country to the same degree as China today,” Julian Ku, a law professor at Hofstra University, told Quartz previously, “I think Trump would be a hero.”

In 1972, Nixon was that hero—the president called his eight-day China trip “the week that changed the world.”