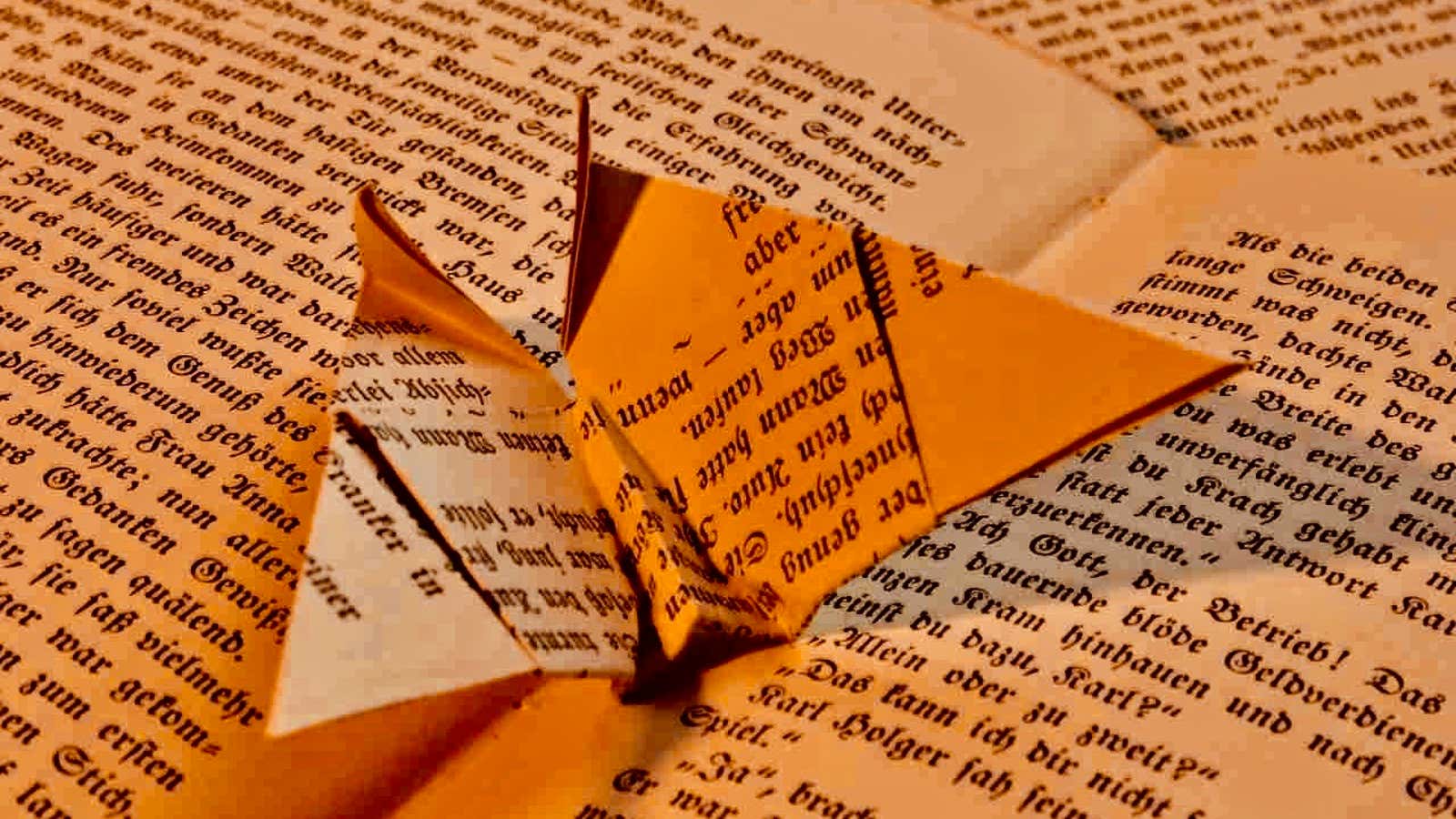

Lots of us love books. But not all bibliophiles express our adoration of these objects the same way. Some see texts as central to their homes’ decor, or turn literature into visual art, repurposing written works into boxes, origami, or statues. And others of us just take what we need, jettisoning the rest.

These differences are at the heart of the internet’s great dust jacket debate. In April, Ariana Rebolini at Buzzfeed declared that “book jackets are bad” after creating a naked bookshelf. She was echoing a sentiment expressed by Michelle Dean at Flavorwire in 2013, who wrote a piece entitled “Against Dust Jackets.”

Critics of the flimsy paper cover argue that dust jackets don’t prevent dust from accumulating, and thus are deceptively named. Plus, they’re a pain. They mar the purity of a plain book, the simple dignity of a hardcover embossed only with important information; title, author, and publisher.

Disposable covers have their defenders, however. Eric Levenson at The Atlantic responded to Dean’s critique, asking, “What did the poor dust jacket ever do to deserve such scorn?” In his view, the removable covers exist to remind us that the book is a precious object. “Take care of what’s between these two covers, the dust jacket says, even as it tries to draw you in.”

The problem is that, rather than protecting texts, book jackets demand extra attention. As noted in a 2015 Book Riot post, they tear easily. This added flimsy bit is problematic, as even its defenders admit. One Quartz staffer and dust-jacket defender, who shall remain unnamed, says he takes jackets off to read, putting them back on books for shelving.

Have you ever heard anything more absurd? That’s like saving a favorite item of clothing in order to wear it only in the closet. As a fan of actual jackets, and despite my disdain for paper covers, I respectfully dissent on stylistic grounds.

Instead of coveting extra covers, consider using the dust jacket as wrapping paper, and becoming a textual nudist. Naked books have a great look. They are simple, elegant, and sophisticated, the titles embossed somberly on a mysteriously plain background. These tomes promise timeless greatness, while making every work appear equal. Whereas the jacketed text reflects the design sensibilities of a moment in time, a nude work signals the possibility of endurance.

This may only be an illusion, but it’s one I like to sustain until the very moment I toss a tome. Then, when I’m getting rid of it, I remind myself of what Ray Bradbury’s words in Farenheit 451: A Novel, his quintessential work on book-burning. “The magic is only in what books say,” he wrote, “how they stitched the patches of the universe together into one garment for us.”

Practicing detachment

Tossing and tearing up texts is a time-honored tradition. The writer Norman Mailer, for example, famously loved books. But not as objects. “When he needed some pages for a public reading, he often tore them out of the book rather than carry it,” writes J. Michael Lennon in the Times Literary Supplement.

There are good reasons to cut up book, even if you appreciate paper and print. One is that certain parts of a work may be inappropriate for some readers. I once sent my teenage nephew a complete version of Yamemoto Tsunetomo’s Hagakure, best known in English as The Book of the Samurai, hoping he’d develop the discipline of an ancient Japanese warrior. But his mother didn’t love the gift, rightly resisting the book’s suggestion that suicide can be an act of honor. Relenting, I created a “greatest hits” version, cutting the best bits from the original and pasting them into a new notebook, comprised of purely motivational quotes.

Other reasons for book destruction, or deconstruction, relate to space and taste. As a frequent mover, I own few texts, and visitors to my home could get the impression that I’m illiterate. That’s not so; I just get rid of most books as soon as possible, and am not gratified by piles that remind me of all I’ve consumed.

Some works deserve a repurposing, however, though not all are suited to the effort. A novel may be enjoyable and full of delightful lines but just recalling the style, ideas, and sentiments expressed within is probably fine.

But if a book contains invaluable yet difficult-to-memorize guidance, or if academic requirements are involved, slicing and dicing is useful. Repurposing a work both cements important ideas in my mind and leads me to deeper engagement with the text as I cull important parts while also saving space. For this reason, I turned almost every assigned law school text into a mini-book, a system that successfully saw me through three years of grueling studies and two state bar examinations.

Similarly, I’ve cut and pasted different translations of the Tao Te Ching into a single notebook, attempting to create one great, personalized version of an already-short work. Various English interpretations of the Chinese text offer different insights into the verses, so I pick my favorites and create tiny guides (none of which ultimately survive).

Repurposing takes work. Cutting a text isn’t quick business. It’s slow and deliberate, best done after a book has been reviewed repeatedly, underlined, annotated, and basically made illegible to anyone else. In the process, the book shifts from an external abstraction to a personal project, metamorphosing into a new object.

A bibliophile must make peace with impossibilities and impermanence. There will never be enough time to read all the works or reread the great ones as many times as they deserve—until every word is seared in memory, each amazing turn of phrase assimilated. It may be best then to view each as you would a beautiful but doomed love story.

Not every great relationship can last forever, though they may all be formative. Thus, we can feel free to treat our texts like Mailer did. Roughly. As Lennon explains, “Books cringed when they felt his hand.”

The writer wasn’t precious about his own work, either. He gave his friend a first edition of his 1959 Advertisements for Myself with 106 pages missing, noting in the inscription, “God knows what I tore them out for.”