Utilities love solar, as long as they own it. The idea of customers generating their own solar power, and selling it back to the grid, strikes fear into big power companies.

Their panic likely just ticked up a notch. On May 9, California’s energy commission unanimously adopted a measure making solar panels mandatory on all new homes starting Jan. 1, 2020. It’s the first state to impose this sort of rule.

Yet, even without regulations like this, building homes without solar panels may not make financial sense within a decade or two.

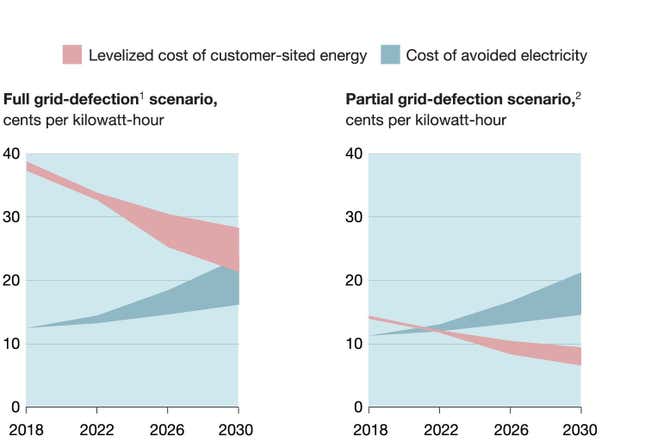

A defection day is coming: the moment when people stop buying their electricity from the grid, and just generate it themselves. In a 2017 study, McKinsey examined the economics of power generation, and found that as soon as 2020, it will make more economic sense for the majority of US homeowners to generate and store 80% to 90% of their electricity on site while only using the grid as a backup. That’s “partial-grid defection.” Full grid-defection, or leaving the electric-power system completely through the installation and use batteries and solar, should arrive around 2028, the McKinsey report predicts.

Even today, California’s energy commission estimates, the average homeowner would only have to pay $40 per month for a solar system that shaves off $80 on monthly heating, cooling, and lighting bills.

California’s decision may usher in grid-defection day even sooner. By instantly creating a massive new market for solar panels in the world’s fifth-largest economy, the new regulations should drive down costs of every aspect of the home-solar market—panels, installations, and infrastructure—and force a massive, imminent restructuring of electricity markets.

Home solar upends utilities’ business model. Utilities tend to make their money when they build big, expensive infrastructure like power plants. Because most are regulated monopolies, they earn a fixed rate of return, set by government commissions, on these projects. While this ensures a steady supply of electricity, it tends to lead to what industry watchers call “gold-plating:” building out expensive capacity that may not be needed in the future. That’s a huge risk for utilities burdened by expensive fossil fuel plants in an age of ever-cheaper renewables. Every time someone stops buying electricity from the grid, the remaining customers must pay for the utilities’ total fixed costs for decades. That raises individual electricity rates for those who remain, and incentivizes customers to break up with the utility even sooner. Then the cycle intensifies. Precisely this scenario has played out in parts of Australia (paywall).

“The only way to pay for the grid is as a network,” an interconnected set of transmission and storage assets, said McKinsey’s David Frankel, a co-author of the report. “It’s very counter to what the industry has seen.”

California regulators estimate that 85% of state residents will partially or fully defect from investor-owned utilities by 2020. And, despite the fact that home solar itself is in the midst of a slowdown across the US, we’re only decades away from seeing this scenario play out across the country.

After at least 16 consecutive years of growth, solar installations fell for the first time last year. Five of six biggest home-solar companies have disappeared, slashed new spending, or been acquired in recent years, says Vikram Aggarwal, the founder of EnergySage, a marketplace where people can buy and sell home solar. Verengo Solar and Sungevity filed for bankruptcy, NRG sold its solar assets, Vivint cut back on its solar installations, and SolarCity was acquired by Tesla and nearly eliminated its marketing budget in the process.

But Aggarwal argues that home solar’s troubles are just a “temporary shakeup.” Instead, he argues, the industry is restructuring for expansion. It installed estimated 2,500 MW last year, a number it will likely top in 2018. Installers are now primarily local (as most construction businesses are), shedding expensive vertical integration models like SolarCity’s model. Expansion is due to resume in the most promising markets in the US like California, Arizona, Nevada, and the eastern seaboard states—where, already, the costs of installing home-solar pays for itself through energy savings in only seven to eight years.

Correction: A previous version of this post stated the incorrect date of adopted a measure making solar panels mandatory on all new homes: it is Jan. 1, 2020.