Europe’s biggest singing contest just stood up to Chinese censorship of LGBT content

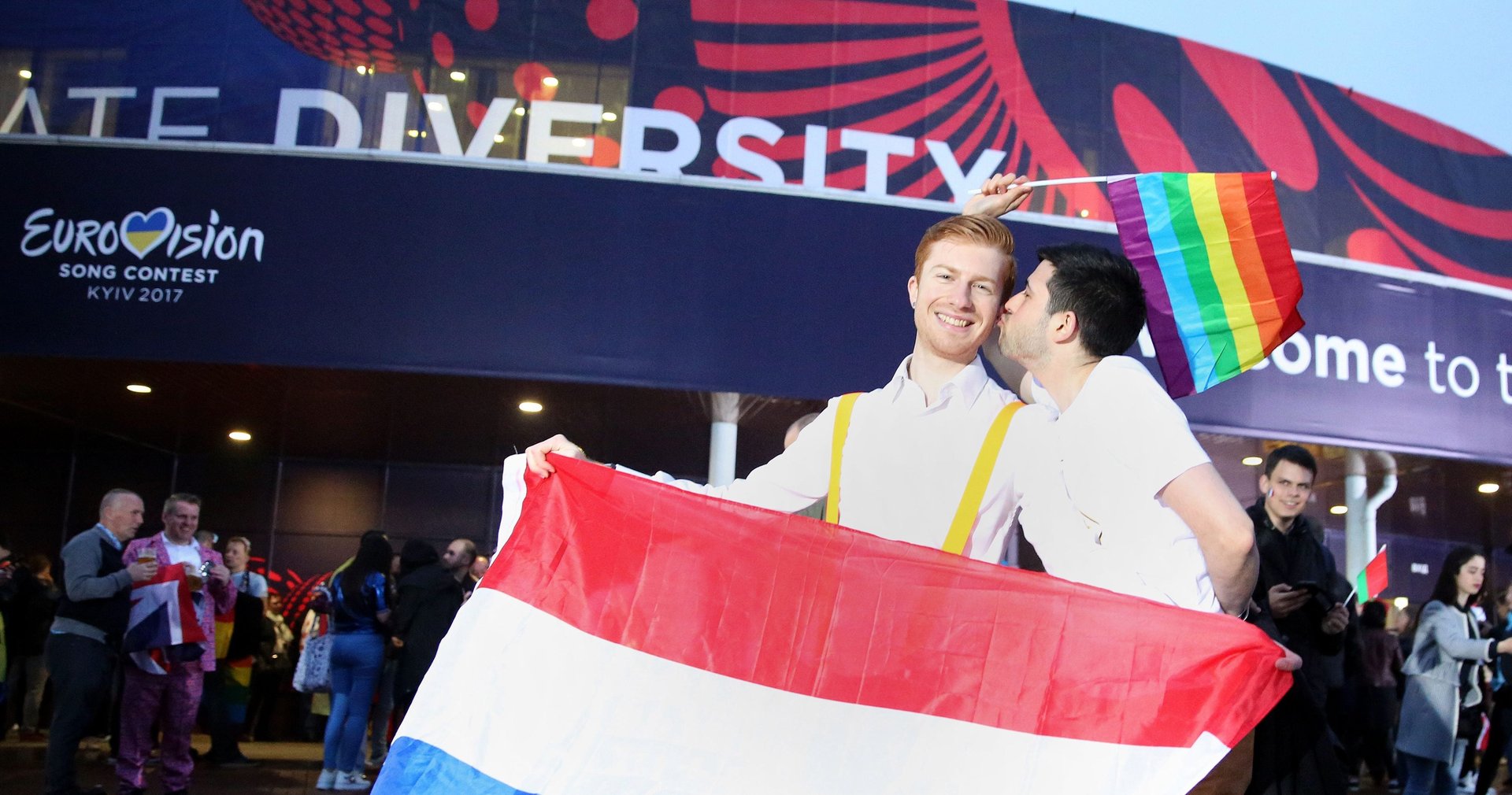

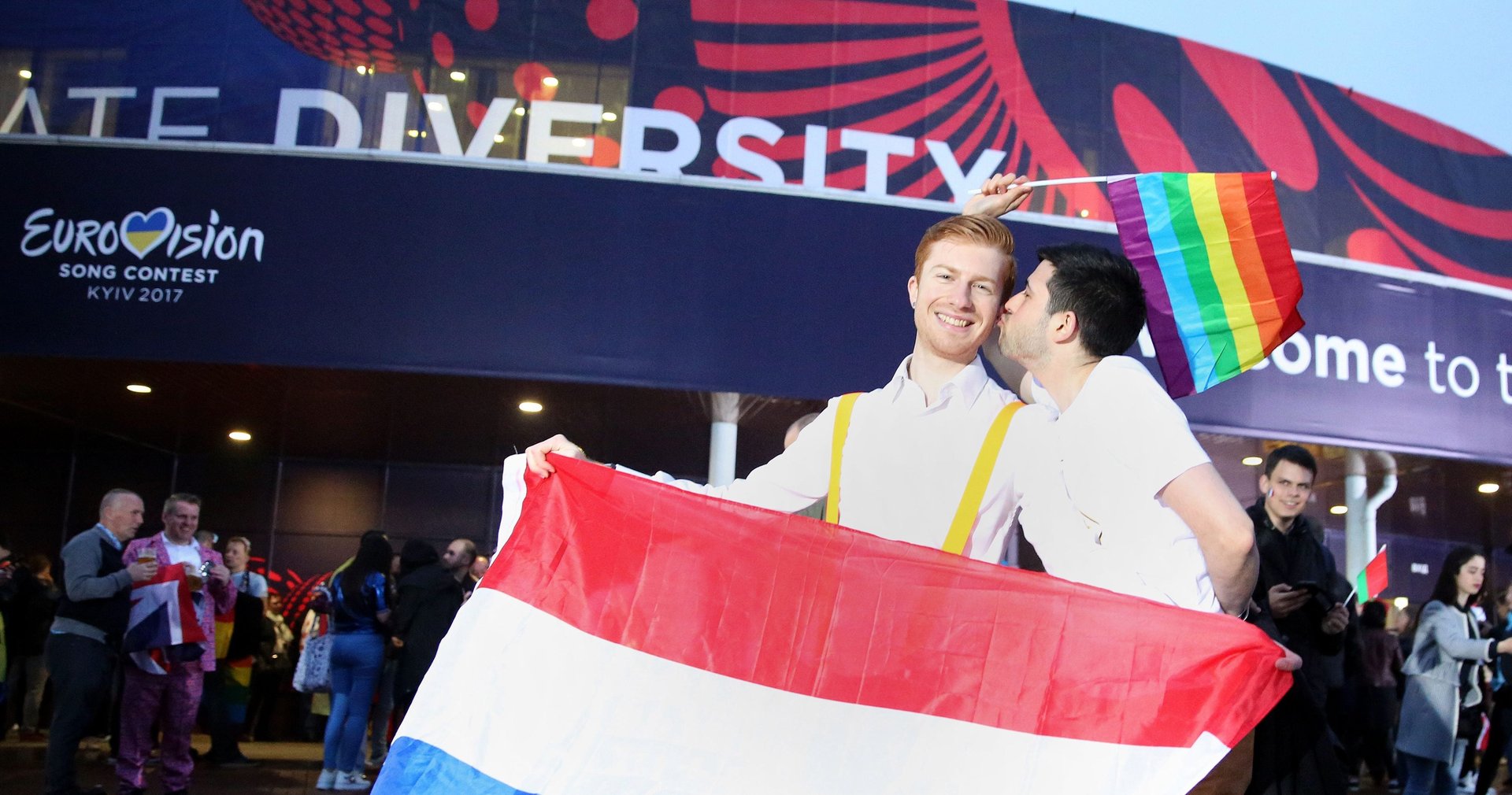

The Eurovision Song Contest—an annual singing competition that brings together countries from all around Europe and beyond for an evening of (at times politically charged) entertainment—is also a celebration of LGBT culture. Chinese viewers, however, didn’t get to see that part of the contest this year.

The Eurovision Song Contest—an annual singing competition that brings together countries from all around Europe and beyond for an evening of (at times politically charged) entertainment—is also a celebration of LGBT culture. Chinese viewers, however, didn’t get to see that part of the contest this year.

Mango TV, an online video-streaming platform linked to Chinese broadcaster Hunan TV, blacked out the performances of Albania’s and Ireland’s contestants during Tuesday’s (May 8) broadcast of the first Eurovision semifinal. A rainbow flag waved in the crowd was also censored.

Ireland’s entry, Ryan O’Shaughnessy, depicted a love story between two men, as two male dancers on stage held hands during the performance.

Chinese social network Sina Weibo in April imposed a ban on LGBT content on its platform as part of a three-month “clean up” campaign to create a “clean and harmonious” environment, the latest in a series of moves by Chinese authorities to stamp out references to homosexuality in the media. Sina Weibo later retracted the ban after an unusually loud, and effective, outcry from supporters of LGBT rights in China.

Albanian singer Eugent Bushpepa, on the other hand, may have been censored because he is heavily tattooed, according to Chinese state tabloid Global Times. China’s media regulator earlier this year instituted a ban on “unhealthy” elements, including tattoos, from being shown on TV. That led to inked soccer players covering up their tattoos with bandages on televised matches.

The European Broadcasting Union (EBU), which operates Eurovision, terminated its contract with Mango TV in response, ahead of the competition’s final that will be held in Lisbon on Saturday (May 12). O’Shaughnessy, the Irish entrant, said he welcomed the EBU’s decision. “Love is love, it doesn’t matter whether it’s between two guys, two girls. I think this is a really important decision by the EBU, they haven’t taken this lightly,” he said in an interview.

In 2015, as the competition tried to expand its viewership outside of Europe, it invited Australia to participate and partnered with Mango TV to broadcast Eurovision live in China. A Hunan TV executive had then told ESC Daily, a site dedicated to Eurovision news, that China would be open to the possibility of participating in the contest as Australia did.

If China hopes to deepen its involvement with Eurovision—won by an Israeli transgender singer in 1998 and then by an Austrian drag queen in 2014—it better start getting comfortable with LGBT people, or its censors will be doing a lot of scrubbing.